EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Communication from the Commission

ENERGY FOR THE FUTURE:

RENEWABLE SOURCES OF ENERGY

White Paper for a Community Strategy

and Action Plan

COM(97)599 final (26/11/1997)

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 Setting the Scene p.4

1.1 The General Framework p.4

1.1.1 Introduction p.4

1.1.2 The Current Situation p.4

1.1.3 The Need for a Community Strategy p.6

1.2 The Debate on the Green Paper p.8

1.3 Strategic Goals p.9

1.3.1 An Ambitious Target for the Union p.9

1.3.2 Member States Targets and Strategies p.10

1.3.3 Possible Growth of RES by Sector p.10

1.4 Preliminary Assessment of some of the costs and benefits p.11

2 Main Features of the Action Plan p.14

2.1 Introduction p.14

2.2 Internal Market Measures p.14

2.2.1 Fair Access for Renewable to the Electricity Market p.14

2.2.2 Fiscal and Finance Measures p.15

2.2.3 New Bioenergy Initiative for Transport, Heat and Electricity p.16

2.2.4 Improving building regulations : its impact on town and country

planning p.18

2.3 Reinforcing Community Policies p.18

2.3.1 Environment p.19

2.3.2 Growth, Competitiveness and Employment p.19

2.3.3 Competition and State Aid p.19

2.3.4 Research, Technology, Development and Demonstration p.20

2.3.5 Regional Policy p.20

2

2.3.6 Common Agricultural Policy and Rural Development Policy p.21

2.3.7 External Relations p.23

2.4 Strengthening co-operation between Member States p.24

2.5 Support Measures p.25

2.5.1 Targeted promotion p.24

2.5.2 Market Acceptability and Consumer Protection p.25

2.5.3 Better positioning for RES on the institutional banks and

commercial finance market p.25

2.5.4 Renewable Energy Networking p.26

3 Campaign for take-off p.27

3.1 Introduction p.27

3.2 Key Actions p.27

3.2.1 1.000.000 photovoltaic systems p.27

3.2.2 10.000 MW of large wind farms p.29

3.2.3 10.000 Mw

th

of biomass installations p.29

3.2.4 Integration of Renewable Energies in 100 Communities p.30

3.3 Estimates of some of the costs and benefits p.30

4 Follow-up and Implementation p.32

4.1 Implementation and Monitoring of Progress p.32

4.2 Internal Co-ordination of E.U. Policies and Programmes p.32

4.3 Implementation by Member States and Co-operation at

EU level p.32

4.4 Implementation of Action Plan - Next Steps p.33

3

ANNEXES

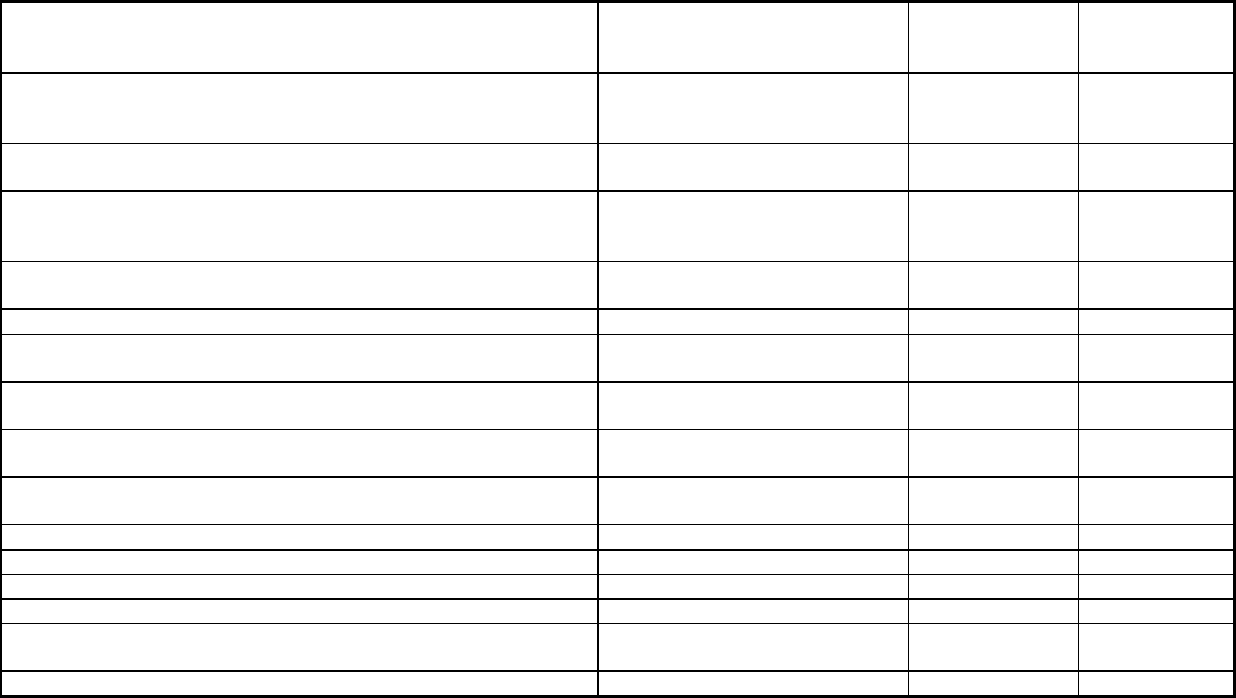

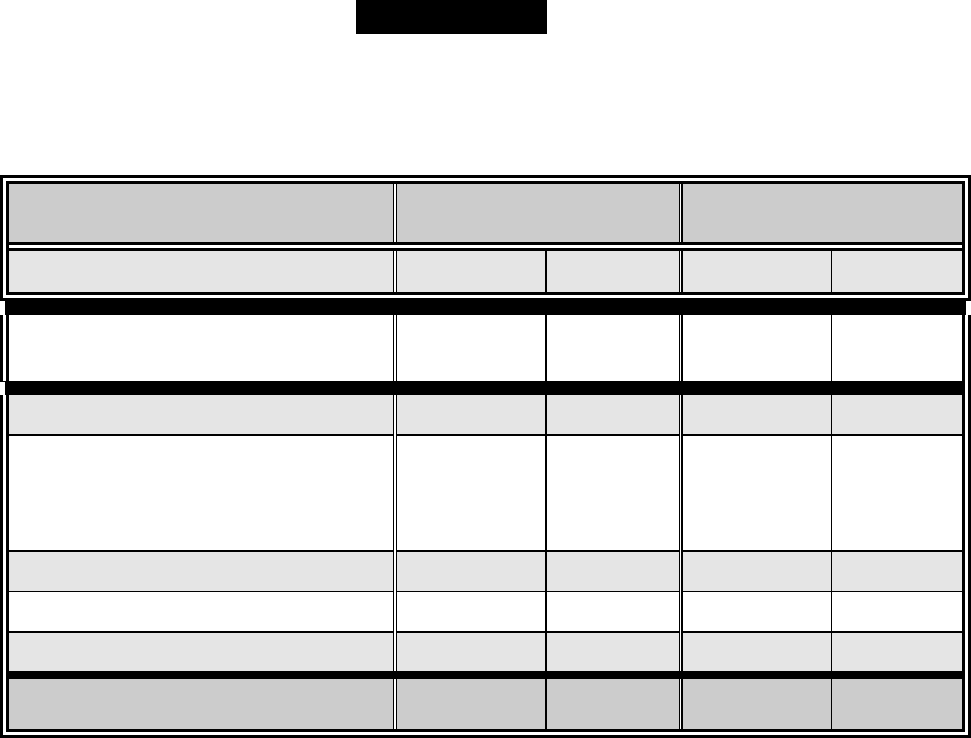

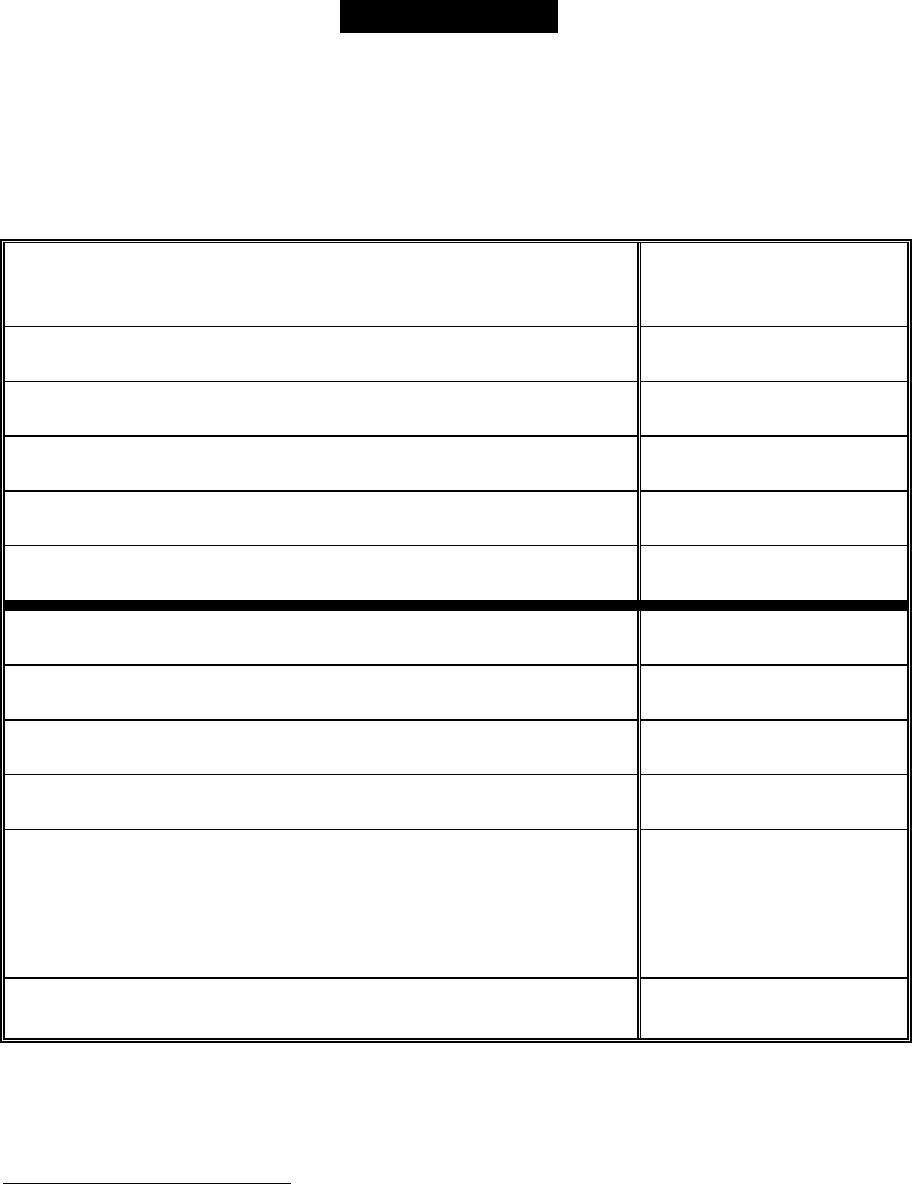

I Preliminary Indicative Action Plan for RES 1998-2010 p.34

II Estimated Contributions by Sector - A scenario for 2010 p.37

II.1 Biomass p.37

II.2 Hydro Power p.39

II.3 Wind Energy p.40

II.4 Solar Thermal p.40

II.5 Photovoltaics p.41

II.6 Passive Solar p.42

II.7 Geothermal and Heat Pumps p.42

II.8 Other Renewable Technologies p.43

II.9 Achieving the Overall Community Objective for RES p.43

II.10 Estimated RES contributions in Electricity and Heat

generation p.43

II.11 Assessment of some of the costs and benefits p.43

III Member States plans and actions for RES development p.45

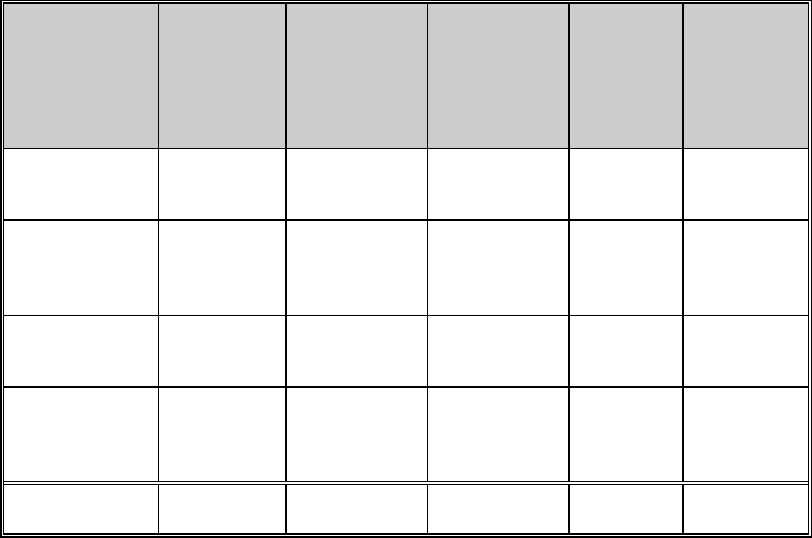

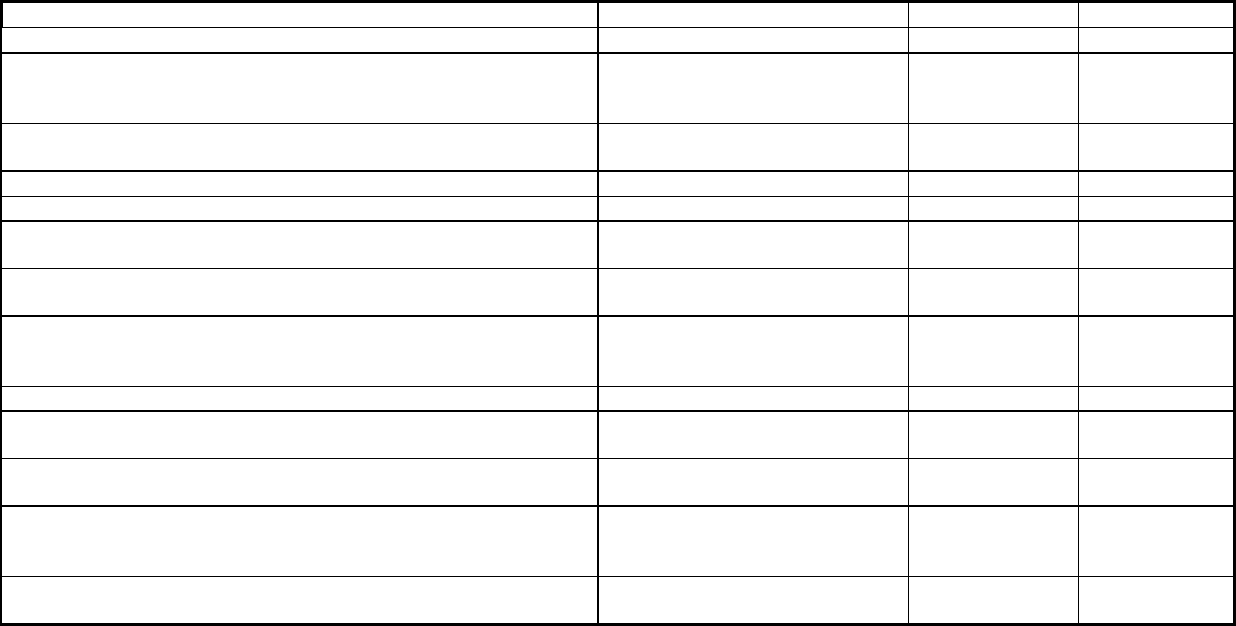

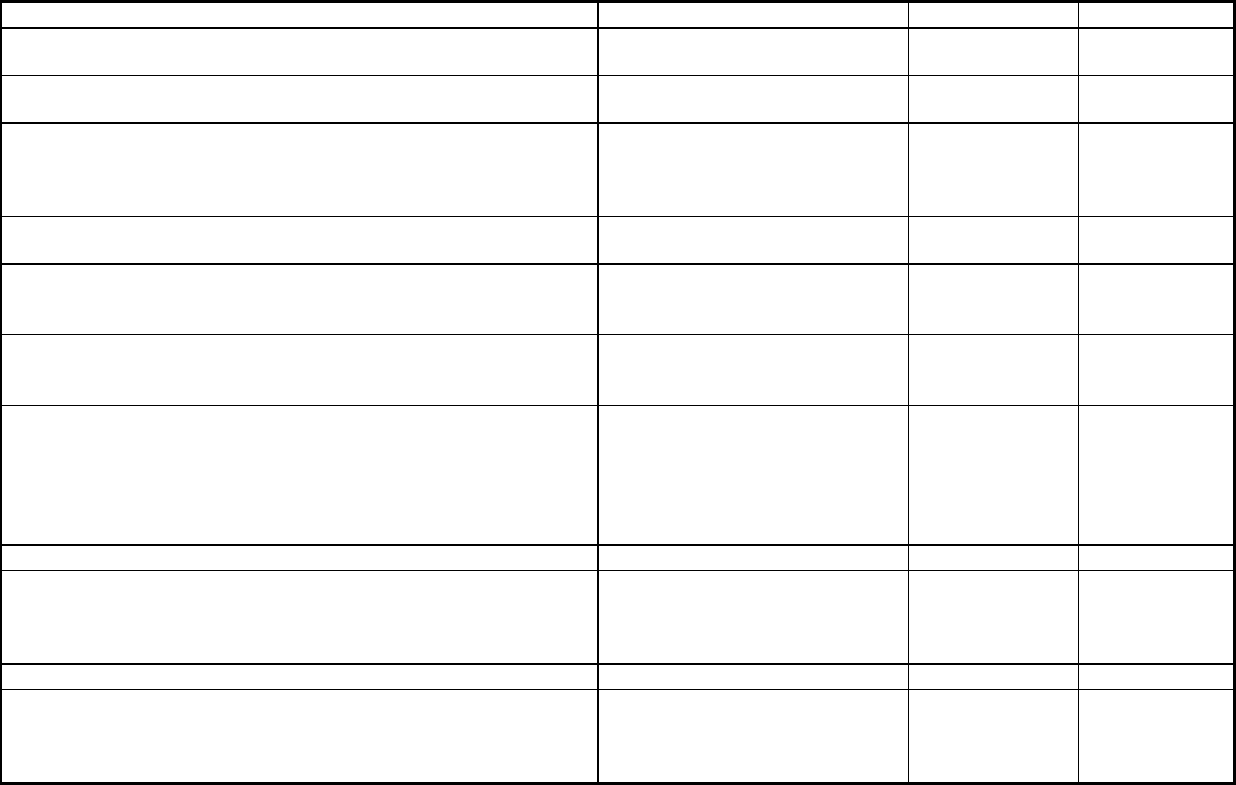

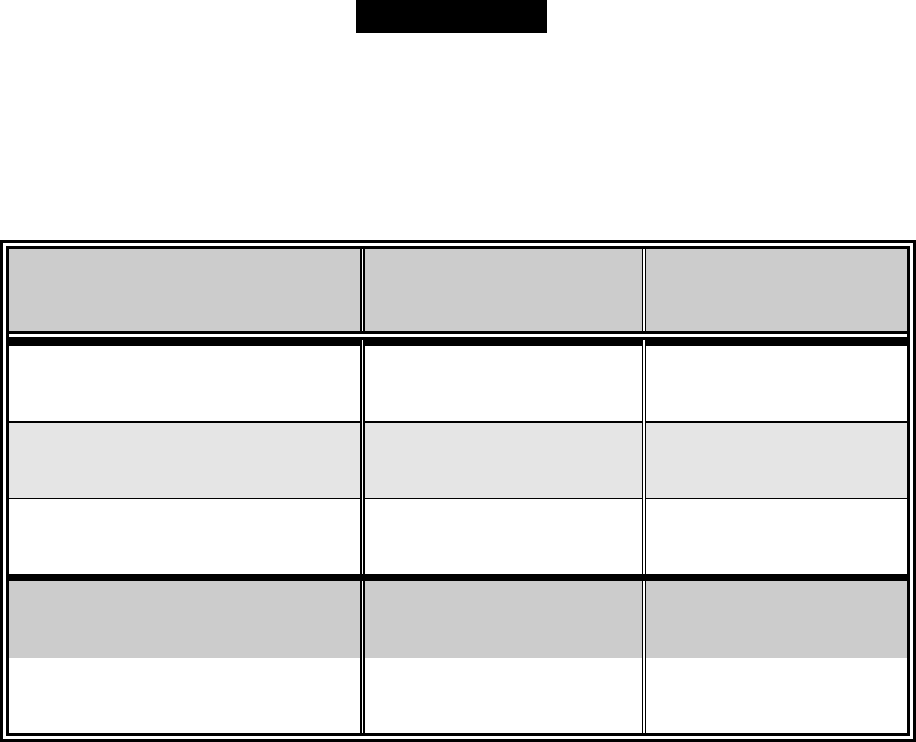

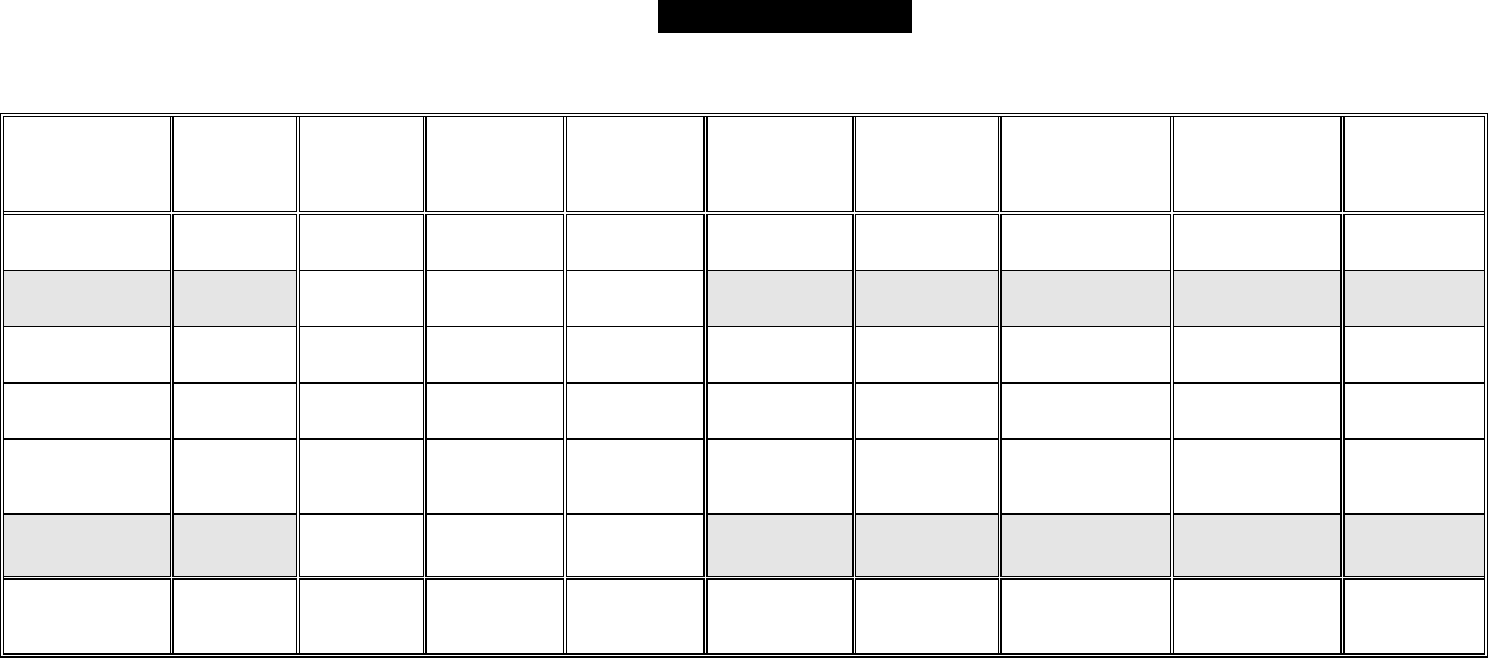

TABLES

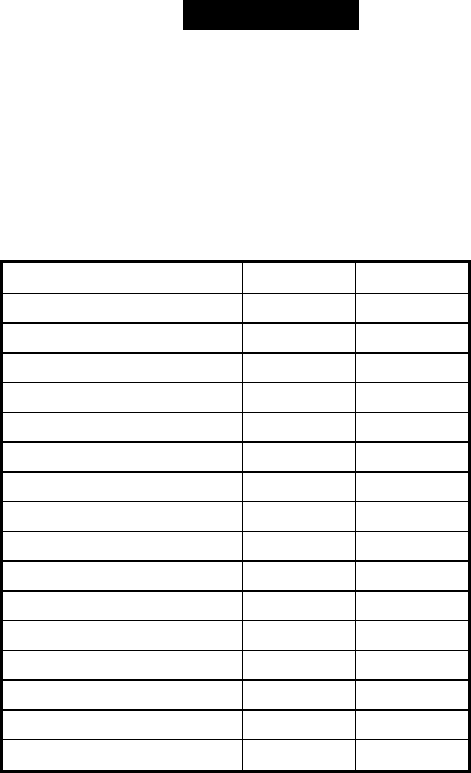

1. Share of Renewable Energy Sources in Gross Inland Energy

Consumption p.47

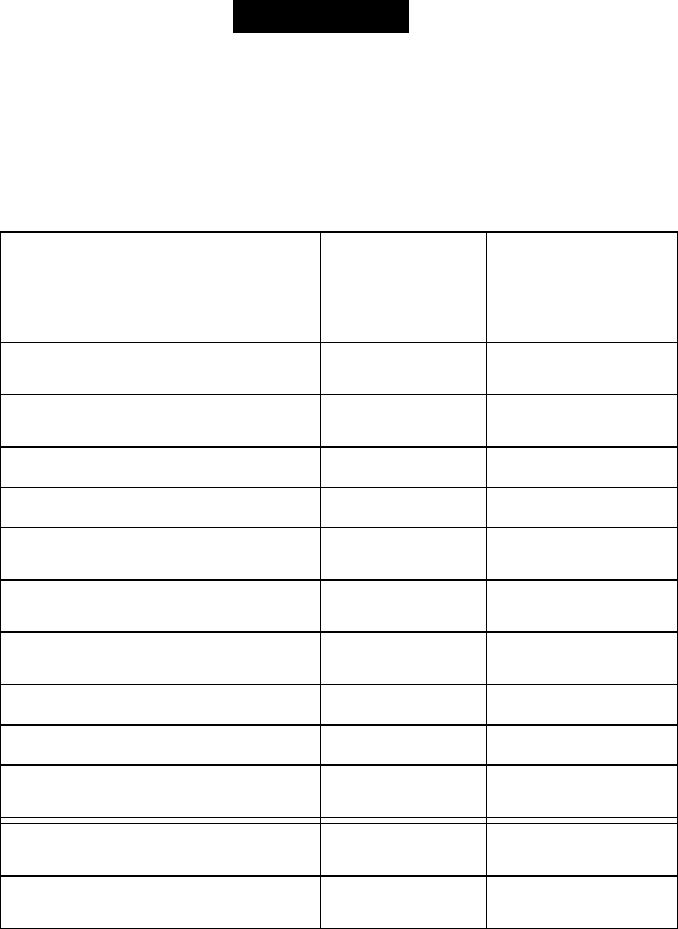

1A Estimated contributions by Sector in the 2010 scenario p.48

2. Current and Projected Future Gross Renewable Energy

Consumption (Mtoe) for 2010 p.49

3. Current and Projected Electricity Production by RES for 2010 p.50

4. Current and Projected Heat Production (Mtoe) for 2010 p.51

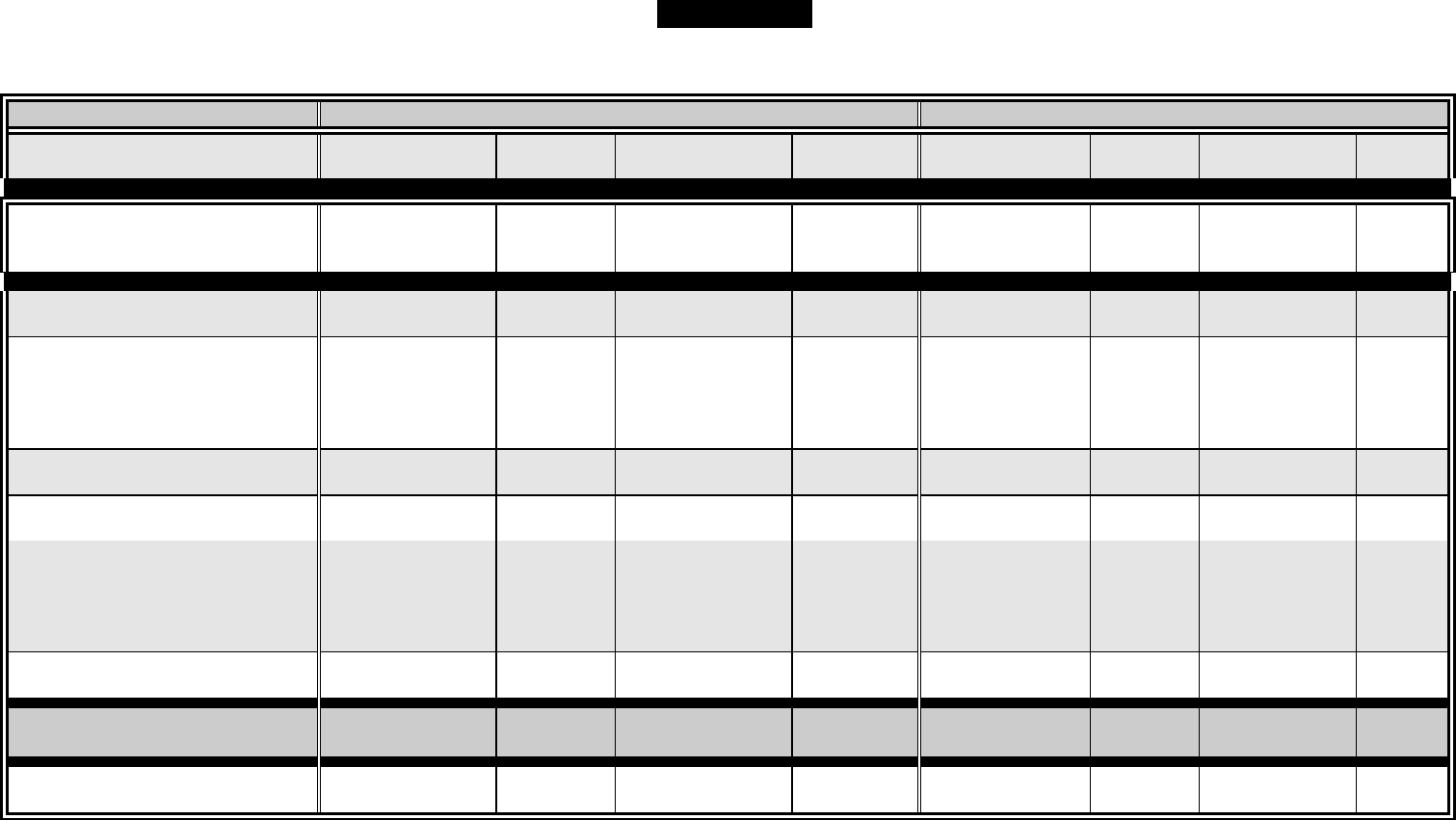

5. Estimated Investment costs and benefits of the overall

Strategy in the 2010 scenario p.52

6. Estimated Investment costs and benefits by sector p.53

4

Chapter 1 Setting the Scene

1.1 The General Framework

1.1.1 Introduction

Renewable sources of energy are currently unevenly and insufficiently exploited in

the European Union. Although many of them are abundantly available, and the real

economic potential considerable, renewable sources of energy make a

disappointingly small contribution of less than 6% to the Union’s overall gross inland

energy consumption, which is predicted to grow steadily in the future. A joint effort

both at the Community and Members States’ level is needed to meet this challenge.

Unless the Community succeeds in supplying a significantly higher share of its

energy demand from renewables over the next decade, an important development

opportunity will be missed and at the same time, it will become increasingly difficult

to comply with its commitments both at European and international level as regards

environmental protection.

Renewable energy sources are indigenous, and can therefore contribute to reducing

dependency on energy imports and increasing security of supply. Development of

renewable energy sources can actively contribute to job creation, predominantly

among the small and medium sized enterprises which are so central to the

Community economic fabric, and indeed themselves form the majority in the various

renewable energy sectors. Deployment of renewables can be a key feature in

regional development with the aim of achieving greater social and economic

cohesion within the Community.

The expected growth in energy consumption in many third countries, in Asia, Latin

America and Africa, which to a large extent can be satisfied using renewable

energies, offers promising business opportunities for European Union industries,

which in many areas are world leaders as regards renewable energy technologies.

The modular character of most renewable technologies allows gradual

implementation, which is easier to finance and allows rapid scale-up where required.

Finally, the general public favours development of renewables more than any other

source of energy, very largely for environmental reasons.

1.1.2 The Current Situation

Five years after the Rio Conference, Climate Change is again at the centre of

international debate in view of the upcoming “Third Conference of the Parties to the

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” to be held in Kyoto in

December 1997. The European Union has recognised the urgent need to tackle the

climate change issue. It has also adopted a negotiating position of 15% greenhouse

gas emissions reduction target for industrialised countries by the year 2010 from the

1990 level. To facilitate the Member States achieving this objective, the

Commission, in its communication on the Energy Dimension of Climate Change

1

identified a series of energy actions - including a prominent role for renewables.

The Council of Ministers endorsed this when inviting the Commission to prepare an

action programme and present a strategy for renewable energy. In preparation for

the international climate change conference in Kyoto, the Commission confirmed

1

COM (97) 196 final, 14 May 1997, “The Energy Dimension of Climate Change

5

the technical feasibility and economic manageability of the Union’s negotiating

mandate. In a recent Communication

2

, the Commission analysed the

consequences of reducing CO2 emissions significantly, including the implications for

the energy sector. In order to achieve such a reduction, the Union will require major

energy policy decisions, focusing on reducing energy and carbon intensity.

Accelerating the penetration of renewable energy sources isvery important for

reducing carbon intensity and hence CO2 emissions, whatever the precise outcome

of the Kyoto Conference.

The EU’s dependence on energy imports is already 50% and is expected to rise

over the coming years if no action is taken, reaching 70% by 2020. This is

especially true for oil and gas which will increasingly come from sources at greater

distances from the Union, often with certain geopolitical risks attached. Attention

will therefore increasingly focus on security of supply. Renewable energies as

indigenous sources of energy will have an important role to play in reducing the

level of energy imports with positive implications for balance of trade and security of

supply.

Much progress has been achieved towards completion of the Internal Energy

Market. Agreement has been reached in the Council of Ministers on the first phase

of liberalisation of the electricity sector and negotiations in the gas sector are well

under way. Opening the markets for the network-bound energies will bring market

forces into play in sectors which until recently were for the most part dominated by

monopolies. This will provide a challenging new environment for renewable

energies, providing more opportunities but also posing the challenge of a very cost-

competitive environment. Suitable accompanying measures are needed in order to

foster the development of renewables.

Renewable energy sources still make an unacceptably modest contribution to the

Community’s energy balance as compared with the available technical potential.

There are signs, however, that this is changing, albeit slowly. The resource base is

better understood, the technologies are improving steadily, attitudes towards their

uses are changing, and the renewable energy manufacturing and service industries

are maturing. But renewables still have difficulties in “taking off”, in marketing terms.

In fact many renewable technologies need little effort to become competitive.

Moreover, biomass, including energy crops, wind and solar energy all offer a large

unexploited technical potential.

Current trends show that considerable technological progress related to renewable

energy technologies has been achieved over recent years. Costs are rapidly

dropping and many renewables, under the right conditions, have reached or are

approaching economic viability. The first signs of large-scale implementation are

also appearing as regards wind energy and solar thermal collectors. Some

technologies, in particular biomass, small hydro and wind, are currently competitive

and economically viable in particular compared to other decentralised applications.

Solar photovoltaics, although characterised by rapidly declining costs, remain more

dependent on favourable conditions. Solar water heaters are currently competitive

in many regions of the Union.

Under prevailing economic conditions, a serious obstacle to greater use of certain

renewables has been higher initial investment costs. Although comparative costs for

2

COM (97) 481 final, 1 October 1997, “Climate Change - The EU Approach to Kyoto”

6

many renewables are becoming less disadvantageous, in certain cases quite

markedly, their use is still hampered in many situations by higher initial investment

costs as compared with conventional fuel cycles (although operational fuel costs are

non-existent for renewables with the exception of biomass). This is particularly the

case due to the fact that energy prices for conventional fuel cycles do not currently

reflect the objective full cost, including the external cost to society of environmental

damage caused by their use. A further obstacle is that renewable energy

technologies, as is the case for many other innovative technologies, suffer from

initial lack of confidence on the part of investors, governments and users, caused by

lack of familiarity with their technical and economic potential and a general

resistance to change and new ideas.

Globally, Europe is at the forefront for several renewable energy technologies.

Significant employment is associated with the industries concerned in the European

Union, involving several hundred companies, mainly small and medium-sized

enterprises, in primary assembling/manufacturing alone, without taking into account

other service and supply needs. For the new renewable energy technologies (i.e.

not including large hydro-electric power stations and the traditional use of biomass)

the world-wide annual turnover of the industry is estimated to be higher than ECU 5

billion, of which Europe has more than a one third share.

1.1.3 The Need for a Community Strategy

Development of renewable energy has for some time been a central aim of

Community energy policy, and as early as 1986 the Council

3

listed the promotion of

renewable energy sources among its energy objectives. Significant technological

progress has been achieved since then thanks to the various Community RTD and

demonstration programmes such as JOULE- THERMIE, INCO and FAIR which not

only helped in creating a European renewable energy industry in all sectors of

renewables but also in achieving a world-wide leading position. This technological

leadership will be maintained by the contribution of the 5th RTD framework

programme in which the renewable energy technologies will have a central role to

play. With the ALTENER programme

4

, the Council for the first time adopted a

specific financial instrument for renewables promotion. The European Parliament for

its part has constantly underlined the role of renewable energy sources and in a

recent Resolution

5

strongly advocated a Community action plan to advance them. In

its White Paper, “An Energy Policy for the European Union”

6

the Commission put

forward its views as regards Community energy policy objectives and instruments to

achieve them. Three key energy policy objectives were identified, viz. improved

competitiveness, security of supply, and protection of the environment. Promotion of

renewables is identified as an important factor to achieve these aims. A strategy for

renewable energy sources was proposed, and specifically cited in the ‘indicative

work programme’ attached to the Energy Policy White Paper.

At the same time some Member States have introduced some measures to support

RES and related programmes. Some have set up plans and targets aimed at

developing RES in the medium and long term. The share of renewable energies in

the gross inland energy consumption differs widely between Member States, from

less than 1% to over 25% (see table 1). A Community strategy will provide the

3

OJ C 241 of 25.9.1986, p.1

4

OJ L 235 of 18.9.1993, p.41

5

PE 216/788; fin

6

COM(95) 682 of 13.12.1995, “An Energy Policy for the European Union”

7

necessary framework and bring added value to national initiatives increasing the

overall impact.

A comprehensive strategy for renewables has become essential for a number of

reasons. First and foremost, without a coherent and transparent strategy and an

ambitious overall objective for renewables penetration, these sources of energy will

not make major inroads into the Community energy balance. Technological progress

by itself can not break down the several non-technical barriers which hamper the

penetration of renewable energy technologies in the energy markets. At present,

prices for most classical fuels are relatively stable at historically low levels and thus

in themselves militate against recourse to renewables. This situation clearly calls for

policy measures to redress the balance in support of the fundamental environmental

and security responsibilities referred to above. Without a clear and comprehensive

strategy accompanied by legislative measures, their development will be retarded. A

long-term stable framework for the development of renewable sources of energy,

covering political, legislative, administrative, economic and marketing aspects is in

fact the top priority for the economic operators involved in their development.

Furthermore, as the internal market develops, a Community-wide strategy for

renewables is required to avoid imbalances between Member States or distortion of

energy markets. The leading position of the European renewable energy industry

world-wide can only be maintained and strengthened on the basis of a significant

and growing home market.

A policy for the promotion of renewables requires across-the-board initiatives

encompassing a wide range of policies: energy, environment, employment, taxation,

competition, research, technological development and demonstration, agriculture,

regional and external relations policies. A central aim of a strategy for renewable

energy will be to ensure that the need to promote these energy sources is

recognised in new policy initiatives, as well as in full implementation of existing

policies, in all of the above areas. In fact, a comprehensive action plan is required to

ensure the necessary co-ordination and consistency in implementing these policies

at Community, national and local levels.

The role of Members States in the implementation of the Action Plan is crucial. They

need to decide on their own specific objectives witin the wider framework, and

develop their own national strategies to achieve them. The measures proposed in

this White Paper must also be adapted to the particular socio-economic,

environmental, energy and geographic situation of each Member State as well as to

the technical and physical potential of RES in each Member State.

With a view to illustrating the potential effects of specific policy initiatives in the

renewable energy field, the Commission sponsored an exercise referred to as

TERES. The TERES II study

7

builds on one of the scenarios previously developed

in the Commission’s European Energy to 2020

8

report but goes further by adding

various specific renewable energy policy assumptions to form three additional

scenarios. These scenarios predict the contribution of renewable energy sources to

gross inland energy consumption to be between 9.9% and 12.5% by 2010. The

technical potential, however, is much larger.

7

TERES II, European Commission, 1997

8

European Energy to 2020. A Scenario Approach, European Commission, 1996

8

The various scenarios clearly illustrate that renewable energy sources can make a

significant contribution to the energy supply of the European Union. On the other

hand the renewable energy component of the energy mix is very sensitive to

changing policy assumptions. Unless specific incentives are put in place, the large

potential for renewable energy will not be exploited and these sources will not make

a sufficient contribution to the European energy balance.

1.2 The Debate on the Green Paper

As a first step towards a strategy for renewable energy the Commission adopted a

Green Paper on 20 November 1996

9

A broad public debate took place during the

early part of 1997 focusing on the type and nature of priority measures that could be

undertaken at Community and Member States’ levels. The Green Paper has elicited

many reactions from the Community institutions, Member States’ governments and

agencies, and numerous companies and associations interested in renewables. The

Commission organised two conferences during this consultation period where the

issues were extensively discussed.

The Community Institutions have delivered detailed comments on the Green Paper

as well as opinions on what should be the essential elements and the major actions

to be undertaken for a future Community strategy on renewable energy sources and

the role of the Community in this process. The Council in its Resolution

10

on the

Green Paper, affirms that adequate action on renewables is vital for achieving

sustainable economic growth, the aim being a strategy that would lead to improved

competitiveness and a substantial share of renewables in the long term. Thus, it

confirms that Member States and the Community should formulate indicative targets

as a guideline for this ambitious indicative target of doubling the overall share of

renewable in the Community by 2010. The Council Resolution states that such a

comprehensive strategy should be based on certain basic priorities: harmonisation

of standards concerning renewables, appropriate regulatory measures to stimulate

the market, investment aid in appropriate cases, dissemination of information to

increase market confidence with specific actions to increase customer choice. It also

takes the view that adequate provision for the support for renewables in the Fifth

Framework Programme for Research, Technological Development and

Demonstration is required, as well as effective co-ordination and monitoring of

progress in order to optimise available resources.

The European Parliament in its Resolution

11

on the Green Paper recognises the

important role that renewable energy can play in combating the greenhouse effect,

in contributing to the security of energy supplies and in creating jobs in small and

medium enterprises and rural regions. It believes that the European Union urgently

needs a promotion strategy which will tackle the issues of tax harmonisation,

environmental protection and standards, internalisation of external costs, and

ensure that the gradual liberalisation of the internal energy market will not place

renewables at a disadvantage. It proposes a goal of a 15% share of renewables for

the European Union by the year 2010. It calls on the Commission to submit specific

measures to facilitate the large-scale use of renewable energy sources and

advocates certain specific measures. These include the setting of targets per

Member State, the concept of a common energy-related tax model, free non-

discriminatory access to the grid combined with a minimum payment by the utilities

9

COM(96)576 of 20.11.1996, “Energy for the future : renewable sources of energy”

10

Council Resolution n° 8522/97 of 10 June 1997

11

PE 221/398.fin

9

for the electricity supplied from renewable energies, the main features of a plan to

establish a European fund for renewable energies, a strategy for a common

programme to promote renewable energies to include a further 1,000,000

photovoltaic roofs, 15,000 MW of wind and 1,000 MW of energy from biomass.

Parliament’s Resolution also calls for a buildings directive, a plan for greater use of

structural funds, a strategy for the better utilisation of agricultural and forestry

biomass and an export strategy for renewable energy technologies. It reaffirms its

belief in the need to increase the Community budgetary appropriations in support of

renewable energy sources to the level currently used for nuclear research. It also

proposes the constitution of a new Treaty for the promotion of renewable energy

sources. The Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development of the Parliament

has also issued an Opinion in which it considers that the contribution of biomass-

derived energy to the primary energy mix could reach 10% by 2010. It also calls for

a better co-ordination of European Union energy policy and the common agricultural

policy and emphasises the need to make the necessary arable land available under

the latter.

The Economic and Social Committee

12

and the Committee of the Regions

13

have

also presented detailed comments on all chapters of the Green Paper, which also

stress, analyse, and support the overall goals relating to sustainability and the

different ways the potential contribution of renewables can be maximised.

Furthermore, these contributions set out ways in which the role and responsibilities

of regional and local public authorities and other bodies could be best harnessed to

facilitate renewables support and market penetration. Given the predominantly

decentralised implementation of most renewable technologies, practical measures

in this direction would allow recourse to the subsidiarity principle, in the framework

of a Community Strategy and Action Plan, facilitating local authorities in their

decision-making power and environmental responsibility. Moreover, this context is a

prime example where energy policy aims and those of structural and regional policy

can synergise with one another to great effect, as illustrated by the case of rural,

island, or otherwise isolated communities where sustainable development and the

maintenance of a population base can be actively supported by replacement of

inefficient small-scale fossil fuel use by renewables plants. That leads to better

living standards and job creation.

More than 70 detailed written reactions have been received from Member State

agencies, industries, professional associations, regional associations, institutes and

non-governmental organisations following the publication of the Green Paper. The

extensive public debate on the Green Paper and the many contributions received

have provided valuable input for the Commission in drafting this White Paper and in

proposing the Action Plan.

1.3 Strategic Goals

1.3.1 An Ambitious Target for the Union

In the Green Paper on Renewables the Commission sought views on the setting of an

indicative objective of 12% for the contribution by renewable sources of energy to the

European Union’s gross inland energy consumption by 2010. The overwhelmingly

positive response received during the consultation process has confirmed the

12

CES 462/97 of 23-24 April 1997, Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee

13

CdR 438/96.fin, Opinion of the Committee of the Regions

10

Commission’s view that an indicative target is a good policy tool, giving a clear political

signal and impetus to action. The strategy and action plan in this White Paper

therefore, are directed towards the goal of achieving a 12% penetration of renewables

in the Union by 2010 - an ambitious but realistic objective. Given the overall

importance of significantly increasing the share of RES in the Union, this indicative

objective is considered as an important minimum objective to maintain, whatever the

precise binding commitments for CO2 emission reduction may finally be. However, it

is also important to monitor progress and maintain the option of reviewing this

strategic goal if necessary.

The calculations of increase in RES needed to meet the indicative objective of 12%

share in the Union’s energy mix by 2010 is based on the projected energy use in the

pre-Kyoto scenario (conventional wisdom, European Energy to 2020, see footnote 8)

It is likely that the projected overall energy use in the EU 15 may decrease by 2010 if

the necessary energy saving measures are taken post Kyoto. At the same time, the

enlargement of the Union to new Member States where RES are almost non-existent

will require an even greater overall increase. It is therefore considered at this stage,

that the 12% overall objective cannot be refined further. It is in any case, to be

emphasised that this overall objective, is a political, and not a legally binding tool.

1.3.2 Member States Targets and Strategies

The overall EU target of doubling the share of renewables to 12%by 2010 implies that

Member States have to encourage the increase of RES according to their own

potential. Targets in each Member State could stimulate the effort towards increased

exploitation of the available potential and could be an important instrument for

attaining CO

2

emission reduction, decreasing energy dependence, developing

national industry and creating jobs. It is important, therefore, that each Member State

should define its own strategy and within it propose its own contribution to the overall

2010 objective, indicate the way it expects different technologies to contribute and

outline the measures it intends to introduce to achieve enhanced deployment.

Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that both the Community and the Member

States have to build on existing measures and strategies, as well as tackle new

initiatives. Some Member States have developed national Plans for RES and set

objectives for 2010, 2020 or even 2030. Annex III outlines the plans and actions of

Member States for renewables development. Member States are indeed already

making efforts to develop RES and the Community Strategy will provide a framework

to encourage those efforts and to ensure their cross-fertilisation. Action at the level of

the Community can provide added value in terms of the sharing and transfer of

successful technological and market experiences.

1.3.3 Possible Growth of RES by Sector

Achievement of the average 12% overall indicative objective for the Union clearly

depends on the success and growth of the various individual renewable technologies.

Views expressed during the consultation process on the Green Paper confirmed that it

is important to analyse how the overall objective can be achieved by a contribution

from each sector, and hence to estimate the contribution each renewable source is

likely to make. The potential sectoral growth of RES suggested in this Strategy has to

be considered as a first attempt to identify a possible combination of renewable

technologies that could allow the EU to reach the overall target, within technical,

practical and economic limitations. However, renewable energy technologies may well

evolve differently, depending on many factors, including market developments,

options chosen by Members States and technical developments. The estimate share

of different technologies are clearly indicative and will serve to help monitor progress

11

and ensure that each technology makes its optimal contribution, within a clear policy

framework.

The current share of renewables in the energy mix of approximately 6% includes

large-scale hydro, for which the potential for further exploitation in the European

Union, for environmental reasons, is very limited. This means that the increases in the

use of other renewables will have to be all the more substantial.

In Annex II a set of indicative estimated contributions from each renewable energy

source as well as for each market sector are outlined, as a projection of one way in

which the overall desired growth of RES can be achieved. According to the particular,

scenario outlined, the main contribution of RES growth (90 Mtoe) could come from

biomass, tripling the current level of this source. Wind energy, with a contribution of

40 GW is likely to have the second most important increase. Significant increases in

the solar thermal collectors (with a contribution of 100 million m

2

installed by 2010) are

also anticipated. Smaller contributions are foreseen from photovoltaics (3 GWp),

geothermal energy (1 GWe and 2.5 GWth) and heat pumps (2.5 GWth). Hydro power

will probably remain the second most important renewable source, but with a relatively

small future increase (13 GW), keeping its overall contribution at today’s level. Finally,

passive solar could have a major contribution in reducing the heating and cooling

energy demand in buildings. A 10% contribution in this sector, representing fuel

savings of 35 Mtoe, is considered feasible. If the sectoral growth outlined in the

scenario is achieved then the overall doubling of the current share of renewables can

be achieved, as shown in the tables in Annex II. As far as the market sectors are

concerned, the doubling of the current electricity and heat production from

renewables plus a significant increase of biofuel in transport fuel use by 2010 are

important elements in the scenario for achieving the overall Union objective.

1.4 Preliminary Assessment of some of the Costs and Benefits

In order to assess the feasibility of achieving the overall Community objective, the

necessary costs have to be estimated. Equally important, however, is the estimation of

the related benefits. The doubling of the current market penetration of renewable

energies by 2010 will have beneficial effects among others in terms of CO

2

emissions;

security of supply and employment. In table 6 of Annex II the estimated investment costs

required to achieve the target together with the estimated benefits are presented. The

total capital investment needed to achieve the overall target is estimated at 165 billion

ECU for the period 1997-2010. What is more relevant, however, is the net investment

which is estimated at 95 billion ECU

14

. However, it must be underlined that there are very

significant avoided fuel costs.

In table 5 of Annex II these figures are compared with the total investment of the energy

sector for the same period, as projected by the Conventional Wisdom scenario of the

“European Energy to 2020” study of the Commission. If we consider that in this scenario

an amount for investments in renewable energies is already included, the additional net

investment needed if the action plan is to have its full effect is then equal to 74 billion

ECU. In the same table, it can be seen that the doubling of the share of renewables may

require an increase of approximately 30% in the total energy sector investment but it

could create an estimated gross figure of 500,000 - 900,000 new jobs, save annually (in

2010) 3 billion ECU in fuel costs and a total of 21 billion ECU for the period 1997-2010,

14

It has been calculated by taking the total investment and subtracting the investment that would have

been needed if the energy from renewables was provided by fossil fuel technologies

12

reduce the imported fuels by 17.4% and the CO

2

emissions by 402 million tonnes/year by

2010.

This amount of CO

2

savings represents a significant contribution towards the CO

2

reduction needed to successfully combat climate change. The calculation of the figures

in the table needs some clarification. In the recent Communication from the Commission

“Climate Change - the EU approach to Kyoto”

15

it is estimated that the 800 million tonnes

CO

2

emission reduction potential can be achieved with an annual compliance cost of 15

to 35 billion ECU and with a total (primary and secondary) benefit which might range

from 15 to 137 billion ECU per year. From the analysis presented in Annex II, it is shown

that doubling the share of renewables can reduce the CO

2

emissions by 402 million

tonnes per year with respect to 1997. This corresponds to an additional reduction

possibility of 250 million tonnes of CO

2

with respect to the 2010 “business as usual” Pre-

Kyoto scenario used in the Climate Change Communication and one third of the

expected CO

2

reduction target. The difference between figures (402 and 250) is due to

the fact that in the scenario for 2010, an increase of 30 Mtoe in the use of renewable

between 1995-2010 is assumed which corresponds approximately to annual savings of

150 million tonnes of CO

2

by 2010. Therefore, the estimates of CO2 emission reduction

from RES cited in this White Paper results from a technical assessment and represents

the full expected reduction from a doubling of the current share of RES, whereas in the

policy communication on Kyoto, the figure cited is the additional reduction in CO2

emissions to be attained to reach a specific reduction target, over and above what may

have been attained under the specific Conventional Wisdom pre-Kyoto scenario for

2010.

Net employment figures in the renewable energy sector are difficult to predict and

calculate. Real figures exist in the sectors that have reached a certain level of

development. Wind energy, for example, has already created more than 30,000 jobs in

Europe. Each renewable energy technology has its own characteristics as far as the

quality and the kind of employment generated. Biomass has the particularity of creating

large numbers of jobs for the production of raw material. Photovoltaics creates a large

number of operational and maintenance jobs, since PV installations are small and

dispersed. Hydro is not expected to create more jobs than those already existing in

Europe.

Detailed estimations of net employment have been made in the TERES II study using the

SAFIRE market penetration model developed under the JOULE II programme. The

model predicts for 2010 a net employment of 500,000 jobs directly created in the

renewable energy sector and indirectly in the sectors that supply the sector. This is a net

figure allowing for losses of jobs in other energy sectors. Sectorial studies performed

mainly by the industry give much larger employment figures. The European Wind Energy

Association (EWEA)

16

estimates that the jobs to be created in 2010 by the wind sector

will be between 190,000 and 320,000, if 40 GW of wind power is installed. The European

Photovoltaic Industry Association (EPIA) estimates

17

that a 3 GWp installed power in

2010 will create approximately 100,000 jobs in the PV sector. The European Biomass

Association (AEBIOM)

18

believes that the Biomass employment figures in the TERES II

study are underestimated and that employment in the sector will increase by up to

1,000,000 jobs by 2010 if the biomass potential is fully exploited. The European Solar

Industry Federation (ESIF) estimates that 250,000 jobs will be created in order to meet

15

COM(97)481 final - see footnote 2

16

EWEA Strategy Paper ‘97, ALTENER publication, 1997.

17

EPIA, “Photovoltaics in 2010”, European Commission, 1996.

18

Statement of AEBIOM on the Green Paper of the European Commission, February 1997.

13

the solar collector 2010 market objective. While it is not possible to reach any hard

conclusions as is the likely cumulative level of job creation which would derive from

investments in the various forms of renewable energy sources, it is quite clear that a pro-

active move towards such energy sources will lead to significant new employment

opportunities.

An important additional economic benefit not included above is the potential growth of

the European renewable energy industry in international markets. In most technical

areas, European industry in this field is second to none in its ability to provide the

equipment and technical, financial and planning services required for market growth.

This offers therefore, significant business opportunities for exports and possibilities for

expansion of the European renewable technologies industry. A 17 billion ECU annual

export business is projected for 2010, creating potentially as many as 350.000 additional

jobs.

Considering all the important benefits of renewables on employment, fuel import

reduction and increased security of supply, export, local and regional development, etc.

as well as the major environmental benefits, it can be concluded that the Community

Strategy and Action Plan for renewable energy sources as they are presented in this

White Paper are of major importance for the Union as we enter the 21st century.

14

Chapter 2 Main Features of the Action Plan

2.1 Introduction

Without a determined and co-ordinated effort to mobilise the Union’s renewable

energies potential, this potential will not be realised to a significant extent, resulting

in missed opportunity to develop this sector and to reduce greenhouse gas

emissions significantly. If pro-active steps are not taken in a co-ordinated way within

the Union, renewable energies are only likely to emerge slowly from today’s niche

markets to become more widely used and hence fully cost competitive in around

2020, with full market penetration perhaps still years beyond. The Action Plan set

out below aims at providing fair market opportunities for renewable energies without

excessive financial burdens. Increasing the current share of renewables significantly

will not be an easy task, but the benefits to be obtained justify a major effort.

Investments will have to made made both by the private and public sectors, but

these will provide multiple dividends as Europe’s industry and service companies

demonstrate their technological leadership in a globally competitive market. At the

same time, the increasingly liberalised and globalised energy markets present a new

situation, which will have to be used in a positive sense to provide new

opportunities, while new obstacles to RES growth in the electricity sector will have to

be avoided.

The Community Strategy and Action Plan should be seen as an integrated whole, to

be further developed and implemented in close cooperation between the Member

States and the Commission. The challenge facing us requires a concerted and co-

ordinated effort by the various players over time. Measures should be taken at the

appropriate level according to the subsidiarity principle within the coordinated

framework provided by this Strategy and Action Plan. It would be incorrect and

unrealistic to assume that actions need only be taken at Community level. The

Member States have a key role to play in taking the responsibility to promote

Renewables, through national action plans, to introduce the measures necessary to

promote a significant increase in renewables penetration, and to implement this

strategy and Action Plan in order to achieve the national and European objectives.

Legislative action will only be taken at EU level when measures at national level

would be insufficient or inappropriate and when harmonisation is required across

the EU. The Strategy and Action Plan must be flexible and be updated over time in

the light of experience gained and new developments including international

commitments undertaken to reduce CO2 emissions. For this reason, a system of

continuous review is proposed.(see section 4.1. below).

2.2 Internal Market Measures

The following is a list of priority measures aimed at overcoming obstacles and

redressing the balance in favour of renewables, in order to reach the indicative

objective of 12% penetration by 2010.

2.2.1 Fair Access for Renewables to the Electricity Market

Electricity is the single most important energy sector as it accounts for about 40%

of gross energy consumption in the EU15. Access for renewables to the electricity

networks at fair prices is therefore a critical step for their development. The basis for

a Community legal framework largely exists and its implementation will have to

15

provide for the necessary degree of legislative harmonisation. Experience of

liberalisation elsewhere has shown that it can form the basis for a dynamic and

secure role for renewables so long as adequate market-based instruments are

provided.

At present Member States are transposing the internal market in electricity

Directive

19

into national law. The Directive, in Article 8(3), permits Member States to

require electricity from renewable sources to be given preference in dispatching.

Further schemes for the promotion of renewables may also be compatible with the

Directive, pursuant to Article 3 and/or Article 24. Most or all Member States are

planning to include such schemes in their transposition of the Directive. The

Commission is examining closely the different schemes proposed or introduced by

the Member States in order to propose a Directive which will provide a harmonised

framework for Member States to ensure that renewable energies make up a

sufficient contribution to overall electricity supply, both at the EU and at national

level. Different preference schemes for electricity from renewables will be

considered in this context.

Such an approach is an important element towards the creation of a true single

market for electricity. Where significant differences exist between Member States

regarding the extent to which renewable energy is supported and, possibly, the

manner in which any consequent support measures are financed, this may result in

significant trade distortions not related to efficiency.

Other issues to be addressed will include the following :

• the way in which transmission system operators should accept renewable

electricity when offered to them, subject to provisions on transport in the internal

market in electricity Directive;

• the guidelines on the price to be paid to a generator from renewable sources

which should at least be equal to the avoided cost of electricity on a low voltage

grid of a distributor plus a premium reflecting the renewables’ social and

environmental benefits

20

and the manner in which it is financed : tax breaks, etc.;

• • on which categories of electricity purchases such measures fall;

• • with regard to network access, avoiding discrimination between electricity

produced from solar radiation, biomass (below 20 MWe), hydroenergy (below 10

MWe) and wind.

2.2.2 Fiscal and Finance measures

The environmental benefits of renewable energies

21

justify favourable financing

conditions. The so-called “Green tariffs” already offered in certain Member States by

appealing to voluntary environmental solidarity on the part of those consumers -

19

Directive 96/92/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 1996 concerning

common rules for the internal market in electricity. JO L 27, 30.1.1997, p.20

20

This premium could be above 20% of that avoided cost which is about equivalent to the average tax

on electricity in the European Union. The avoided cost introduced here above refers to the cost at

the “city gate”, i.e. the wholesale price at which the grid operator of a municipal low voltage grid

buys electricity from the transmission network. The premium is put equivalent to the tax rebate or

tax exemption of renewable energy as it is currently implemented in those European Union Member

countries which have introduced CO

2

tax. Renewable energy tax exemption is also requested in a

recent Commission proposal modifying the Directive on taxation of energy products

21

Environmental benefits as established by the EXTERNE project (see also Annex II.11)

16

domestic or corporate - able and willing to pay higher rates are not sufficient, nor

appropriate in all cases.

The Commission has already made or will make the necessary additional proposals

for legislation and amendments to existing Directives before the end of 1998,

including tax exemption or reduction on RES energy products on behalf of Member

States “prerogatives” under art. 13 to 16 of the proposed Directive “Restructuring

the Community Framework for the Taxation of Energy Products”

22

;

In some cases it will be appropriate and sufficient for Member States’ authorities to

enact the necessary legislation or other provisions, in areas such as

• flexible depreciation of renewable energies investments;

• favourable tax treatment for third party financing of renewable energies;

• start up subsidies for new productions plants, SME’s and new job creation.

• financial incentives for consumers to purchase RE equipment and services;

The Commission however will also make a survey of the progress made throughout

the Union in this regard by the end of the year 2000, and if this indicates a

remaining need for Union-level measures in certain of the areas listed, the

necessary proposals will be put forward.

Other financial measures, which are proving their value in some Member States, will

also be examined and promoted more widely as appropriate such as:

• so-called “golden” or ‘green’ funds addressed to capital markets. Such funds are

financed from private bank accounts which in this case attract lower interest

rates. The margin consented by the lower interest rate paid to the account holder

is passed on by the bank to the renewable energies investor in the form of

discount rates;

• public renewable energy funds, managed by regulated agencies. The facilities

offered could include revolving funds as well as credit guarantees (renewable

energies bonds) and should in any case conform to the Treaty provisions;

• soft loans and special facilities from institutional banks (see Section 2.5.3)

2.2.3 New Bioenergy Initiative for Transport, Heat and Electricity

Specific measures are needed in order to help increase the market share for liquid

biofuels from the current 0.3% to a significantly higher percentage, in collaboration

with Member States.. The overall environmental effect varies from biofuel to biofuel

and depends, amongst others, on the crop cultivated and the crops replaced.

Promotion of biofuels has to be coherent with the AutoOil Programme and the

European policy on fuel quality, and should take account of the full cycle of

environmental costs/benefits. The role of biofuels in the clean fuel specification for

2005 and beyond is being studied under the Auto Oil II project.

Two new directives, currently under negotiation, concerning transport fuel

23

and

sulphur reduction in liquid fuels

24

already include provisions encouraging the use of

22

Com(97)30 final, 12 March 1997, Proposal for a Council Directive on “Restructuring the Community

Framework for the Taxation of Energy Products”

23

COM(97)248 final, 18 June 1997

24

COM(97)88 final, 12 March 1997 - Proposal for a Council Directive on “Reduction of sulphur content

in certain liquid fuels” and modification of Directive EC/93/12.

17

biofuels for transport, i.e. alcohols and ETBE, vegetable oils and esters for

biodiesel.

Given the fact that currently the production cost of liquid biofuel is three times that of

conventional fuels, a priority effort needs to be placed on further research and other

measures to reduce production costs of biofuels. An increased use of liquid biofuels

at present can only be obtained if there is a high rate of tax relief and subsidised

raw material production. Detaxation of biofuels is currently made on a limited scale,

in the framework of the directive 92/81

25

on harmonisation of the structures of

excise duties, allowing such detaxation on a pilot scale. The Commission proposes

that a market-share of 2% for liquid biofuels could still be considered a pilot phase.

This level may well be reached in the short or medium term in some countries (in

particular Austria, Germany, France and Italy). The Commission has already made

proposals for adjusting the relevant European legislation in order to allow a large

scale liquid biofuels detaxation

26

.

For biogas promotion, production of landfill gas or biogas from the food industry or

farms will be encouraged, in order to obtain with energy and environmental policy

benefits. Fair access to the electricity market will be promoted as indicated in point

2.2.1. above. Measures for biogas will contribute to the achievement of the

Commission’s strategy on reducing methane emissions

27

from manure by using

anaerobic digesters or covered lagoons as well as meeting the objectives on

protection of waters

28

and on landfill

29

.

It is proposed under this strategy that demonstration programmes at European

Union, national, regional and local level should be supported to install recovery and

use systems for intensive rearing. In addition, the Commission will examine the

possibility of integrating biogas actions in the structural funds.

In order for the markets for solid biomass to be further developed, the following

must be actively promoted:

• co-firing or fossil fuel substitution in coal power plants and in existing district

heating networks;

• new district heating or cooling networks as an outlet for co-generation with

biomass;

• greater access to upgraded fuels such as chips and pellets and a more intensive

exploitation of appropriate forest, wood and paper industry residues;

• new scaled up IGCC (Integrated Gasification in Combined Cycle) systems in the

capacity range of 25-50 Mwe based on a mixture of biomass and waste derived

fuels;

• Clean energy generation from municipal waste either by thermal treatment,

landfill gas recovery or anaerobic digestion as long as energy generation from

waste complements and does not replace waste prevention and recycling.

25

OJ L.316 of 31.10.1992, p. 12

26

a) JO n° C 209 of 29.7.1994, p.9 - Proposal for a Council Directive on excise duties on motor fuels

from agricultural sources; b) the above-mentioned in para 2.2.2 proposal for a Directive on the

taxation of energy products - see footnote 17

27

COM (96)557 of 15.11.96

28

OJ L.375 of 31.12.91 - Council Directive 91/676/EEC concerning the protection of waters against

pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources and OJ. C184/20 of 17.06.97, Proposal for a

framework Directive concerning waters protection

29

COM (97) 105 of 05.03.97 - Proposal for a Council Directive on the landfill of waste

18

The Commission has recently published a strategy

30

to promote combined heat and

power. CHP is of paramount importance for the success of biomass

implementation. Almost 1/3 of the new additional biomass exploitation by 2010

could fall in this category. District heating and cooling is also vital to maximise the

financial and economic benefits of cogeneration. Increased use of bioelectricity is

linked, like that for wind and solar electricity, to European Union wide measures for

fair access to the electricity market (see Section 2.2.1).

2.2.4 Improving building regulations: its impact on town and country planning

Energy consumption in the domestic and service sectors can be significantly

reduced by improving energy intensity overall in addition to more use - in retrofitting

as well as for new buildings - of renewables such as solar energy. It is important to

adopt a global approach and to integrate measures of rational use of energy (for the

building envelope as well as for heating, lighting, ventilation and cooling) with the

use of renewable energy technologies. Total energy consumption in this sector

could be reduced by 50% in the European Union by 2010, half of which could be

accounted for by introducing passive and active solar technologies in buildings for

which concrete promotional measures are necessary. This could be facilitated by

amendments to the existing Directives on improving energy efficiency in buildings

31

and to the Directive on building materials

32

in order to include new building materials

for solar efficiency in the standards specifications.

In order to promote the use of RES in buildings, the following specific measures are

proposed:

• incorporation of requirements on the use of solar energy for heating and cooling

in building approvals under current legislative, administrative and other provisions

on town and country planning should be considered;

• promotion of high efficiency windows and solar facades, natural ventilation and

window blinds in new buildings and for retrofitting;

• promotion of active solar energy systems for space heating and cooling and

warm water, e.g. solar collectors, geothermal heating and heat pumps;

• promotion of passive solar energy for heating and cooling;

• encouragement of PV systems to be integrated in building construction (roofs,

facades) and in public spaces;

• photovoltaic electricity sales to utilities from private customers should be priced

so as to allow direct reversible metering;

• measures to encourage the use of construction materials with a low intrinsic

energy content, e.g. timber.

2.3 Reinforcing Community Policies

The priority given to renewable energies in existing Community policies,

programmes and budgets is mostly very low. There is much scope for

reinforcement. It is also important to make the renewable energies potential better

known and to increase awareness among all those bearing responsibility for

Community programmes.

30

COM(97)514 final, “A Community strategy to promote CHP and to dismantle barriers to its

development”

31

Council Directive 93/76/EEC of 13 September 1993 “To limit carbon dioxide emissions by improving

energy efficiency (SAVE).

32

Council Directive 89/106/EEC of 21 December 1988 “On the approximation of laws, regulations and

administrative provisions of the Member States relating to building materials.

19

2.3.1 Environment

The Fifth Environmental Action Plan gives due consideration to renewable energies

and proposes support measures including fiscal incentives

33

The measures in the

Fifth Environmental Action Plan referring to renewable energies, will be

implemented by the year 2000, within the overall framework of the strategy

proposed in this White Paper. The net environmental effects of different renewable

energy sources will be taken into account when implementing different measures.

It is important to underline that a significant increase in the share of renewable

energy sources will play a key role in meeting the Union’s CO2 emission reduction

objectives, in parallel to efforts for energy efficiency and other areas. Measures

related to climate change will take into account the Community Strategy on RES.

2.3.2 Growth, Competitiveness and Employment

The Commission’s White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness and Employment

constitutes an important point of reference for further action on renewable

energies

34

There is indeed a great potential for renewable energies to contribute to

the aims set out in that White Paper. Achieving the indicative objective of 12% in

2010 would lead to an increase in the market for European Industry and could

create a significant number of new jobs as outlined in Section 1.4. The export

market is particularly important as Europe, with its traditional links with Africa, South

America, India and lately South-East Asia, is in a very favourable position. The

following actions deserve particular attention:

• strengthening the competitive edge of European industry in the global renewable

energies market by supporting its ventures into technological leadership and

supporting development of a substantive home market in addition to emerging

export opportunities;

• investigating opportunities for the creation of new SMEs and jobs;

• introducing RES issues in the actions addressed to SMEs under the social fund;

• action for education and training relating to renewable energies within existing

Community programmes.

2.3.3 Competition and State Aid

In considering the various ways in which to promote the development of renewable

energy sources, the positive effects of competition should be taken into account. In

order to make renewables more competitive, priority should be given to ways which

let the market forces function to bring down the costs for producing renewable

energy as rapidly and as far as possible.

When authorising State Aids, the Commission has to take into account the

derogations laid down in Article 92 of the Treaty. The guiding principle for the

Commission in assessing aid for renewable energies, contained in the Community

Guidelines on State Aid for Environmental Protection

35

is that the beneficial effects

of such measures on the environment must outweigh the distorting effects on

competition. The Commission will consider appropriate modifications in favour of

renewable energies in support of its policy in this area during the revision of the

present guidelines taking into consideration the Council’s Resolution on the Green

33

COM (92) 33, ... Fifth Environmental Action Plan - “Towards Sustainability”

34

COM (93) 700.fin - “Growth, Competitiveness and Employment - The Challenges and Ways

Forward in the 21st Century”

35

O.J. n° C72, 10 March 1994, p.3

20

Paper “Energy for the future : renewable sources of energy” which states that

investment aid for renewables can, in appropriate cases, be authorised even when

they exceed the general levels of aid laid down in those guidelines.

2.3.4 Research, Technological, Development and Demonstration

It is generally recognised that there is still great scope for Research, Technological

Development and Demonstration to improve technologies, reduce cost and gain

user experience in demonstration projects on condition that technological

development is guided by appropriate policy measures for introduction into internal

and third country markets and subsequent implementation.

Every kind of action, whether of a fiscal, financial, legal or other nature, is

addressed to facilitate the penetration of the technologies into the market. The

strategic goals presented under 1.3 above have to be reached at the end by the use

of renewable energy technologies, and the role of RTD is to help the development

of technologies which are continuously more efficient.

As research, development and demonstration on renewable energies is moving

strongly into industrial development and higher cost intensity, the financial means to

be earmarked for renewable energy sources should be increased significantly. The

4th Framework Programme for Research, Technological Development and

Demonstration and more particularly the Non Nuclear Energy RTD programme is

giving a priority to Renewable Energies sources as they represent about 45% of its

total budget. The 5th Framework Programme should offer the possibility to finance

the necessary RTD efforts in this area. The specific programme “Competitiveness

and Sustainable Growth” which will be part of the 5th Framework Programme,

contains a key action on energy which indicates clearly the important role of

renewable energies and decentralised production energy systems”.

All RTD activities related to RES should take into account the present Strategy and

Action Plan, including the socio-economic aspects. The complementarity between

RTD on RES and RTD on other technologies should also be encouraged. The role

of RTD is important upstream of the actions in the “Campaign for Take Off”

described later in that it should provide the cost efficient technologies to be used in

this Campaign.

2.3.5 Regional Policy

Renewable energies already feature to some extent in the European Union’s

regional policy. In 1999 new guidelines for 2000-2007 will be decided. The next

multi-annual funds negotiation package will be the occasion to extend, consolidate,

and clarify the aid opportunities available for renewable energies and above all to

increase the weight given to RES within the energy programmes. Decision-making

criteria must reflect the importance of renewables’ potential for less favoured

regions (which are in general dependent on energy imports), peripheral and remote

areas, islands, rural areas, in particular those lacking traditional energies. In those

areas RES have a high potential for new job creation, for the development of

indigenous resources and industrial and service activities (particularly in objective 1

areas). The latter also applies to industrial areas under reconversion and cities

(future objective 2). New incentives should also be undertaken in the tourism sector

as the great potential of renewable energies in this area is still largely unexplored.

The Community will give support to regional and local projects and planning in the

framework of its promotional programmes such as ALTENER (see 2.5.1). However,

21

it is essential to encourage the Member States to include RES implementation plans

in the programmes that they will submit to the structural funds for co-financing

(ERDF and accompanying Community Support Frameworks), so that the share of

RES in energy programmes under the Objective 1 CSF could reach at least 12 %.

This would reflect fully the objective set out in this White Paper for renewable

energy consumption by 2010. However, in order to stimulate a shift towards

renewable energy use so that this objective can be reached at MS level, a

considerably higher engagement of the structural funds seems appropriate. Since

the demand for funding for RES projects has to be Member State driven, effort has

to be put in explaining the possibilities for RES funding and raising awareness on

their potential and benefits for the regions. Other programmes for Objective 2

regions should also contribute to the promotion of RES.

It is important for the Commission to highlight that regional funds invested in

renewable energy sources development could contribute to increased standards of

living and income in less favoured, peripheral, island, remote or declining regions in

different ways :

• favouring the use of local resources and therefore indigenous development;

• being usually labour intensive, they could contribute to the creation of local

permanent jobs;

• contributing to reduce the dependency on energy imports;

• reinforcing energy supply for local communities, green tourism, preserved areas,

etc.;

• contributing to develop the local R&TD and Innovation potential, through the

promotion of specific research-innovation projects adapted to local needs.

The CSF sub-programmes for R&TD and innovation should also give particular

attention to projects aiming at the development of new technologies and processes

adapted to local and regional needs in the areas of RES.

2.3.6 Common Agricultural policy and rural development policy

Agriculture is a key sector for the European strategy of doubling the share of

renewable energies in gross energy demand in the European Union by 2010. New

activities and new sources of income are emerging on-farm and off-farm. Among

those, the production of renewable raw materials, for non-food purposes in niche

markets or the energy sector, can represent a new opportunity for agriculture and

forestry and contribute to job creation in rural areas

36

The reference in Agenda 2000 refers to the encouragement of renewable energies.

In particular biomass should be fully implemented using all available policy

instruments be they agricultural, fiscal or industrial. In the future CAP alternative

use for agricultural products will be a major element. Member States should be

encouraged, in the context of the national aid regimes, to support renewable

energies.

Within the future rural development policy, the Commission will encourage

Member States and regions to give renewable energy projects a high priority within

their programmes for rural areas. However, the regions will continue to have to

assume their responsibility for the selection of the projects.

36

COM(97)2000 Vol.I, p 26 (EN)

22

The Common Agricultural Policy could contribute by supporting the biomass energy

sector to increase standards of living and income in different ways :

• developing energy crops and utilising agricultural and forestry residues as a

reliable source of raw material, under the reformed common agricultural policy,

negotiated in accordance with Agenda 2000, making full use of the results of the

research and development policy;

• giving support for bio-based renewable energies under the rural development

policy and other ongoing programmes;

• supporting the regions by co-financing innovative, demonstrative and

transferable renewable energy projects, such as the installation of combined

solar, wind and biomass heat and electricity production under a new Community

initiative for rural areas, as it is already possible within the existing LEADER

programme;

• applying the regulation 951/97 on processing and marketing of agricultural

products in relation to renewable energy products wherever feasible;

the Commission will table a proposal enabling Member States to make the granting

of direct payments for arable crops and set-aside conditional on the respect of

environmental provisions, allowing them to be increasingly used to pursue

environmental objectives

37

.

The existing possibilities under Regulation 2078/92 will be reviewed in the context of

Agenda 2000. In this context, programmes which reduce environmental pressures

from biomass-production and other uses under the agri-environmental objectives

should be developed. In particular, schemes where energy crops are produced

using reduced water supply, low inputs, by organic methods or harvested in a way

to promote biodiversity etc could attract a premium. The Commission could

envisage more agri-environmental schemes being developed by national authorities

to support energy crops respecting the fact that priorities for programmes would

continue to be set by regional needs and potentials.

On a European forestry strategy the European Parliament, in its “Thomas Report”

has called on the Commission to put forward a legislative proposal. This report,

inter alia, considers the need for adding value to biomass through energy production

including a wide range of instruments. The report is currently under examination by

the Commission, and particular attention will be paid to this point.

Non food policy should also provide for support for energy uses of agricultural

products, by-products and short rotation forestry. The Commission intends to

examine the adequacy of existing instruments particularly in the sense of the need

to promote RES and to improve further harmonisation. Some support is in fact

already provided for in the European legislation, such as 1586/97 (non food set

aside) Regulation 2080/92 (forest measures), 2078/92 (agro-environmental

measures) and 950/97 (improvement of efficiency in the agricultural sector). Full use

should be made of those existing Regulations.

37

COM(97)2000 Vol. I, p 29 (EN)

23

2.3.7 External Relations

Information on and promotion of RES is important for third countries, especially as

they will also have to contribute to global CO2 emission reductions. In that respect,

it is important to promote RES in the European assistance programmes, such as

PHARE, TACIS, MEDA, the European Development Fund and other Lomé

Convention facilities, as well as in all relevant co-operation and other agreements

with developing or industrialised third countries, taking into account the possibilities

and constraints of each programme. For PHARE and TACIS, the promotion of

renewable sources has to be considered in the context of the economic and energy

sector reform priorities of these programmes.

A proactive co-operation and export policy to support renewable energies will be

stimulated, by enlarging the scope and basis of the relevant European Union energy

programmes such as SYNERGY, as well as the Scientific and Technological

Cooperation components of the 5th RTD Framework Programme. The action list

should include the following:

• support for co-operation on energy planning and integrated resource planning

with emerging economies, in order to optimise exploitation of the available

renewable energy potential;

• support for exporters, in the form of credit guarantees and “currency turmoil”

insurance and in the organisation of trade missions, fairs, joint workshops etc.;

• • collaboration in the implementation of the “Word Solar Programme 1996-2005”

which intends to realize worldwide, and especially in the developing countries,

high priority regional and national projects;

• • cooperation with the international financing organisations such as the World

Bank and the Global Environment Facility GEF.

Special action concerning ACP Countries :

• a special initiative to promote solar electricity (photovoltaics for deprived rural

areas in third countries currently without electricity)

38

;

• encourage increased use of alternative renewable energy sources to resolve the

problems caused by overconsumption of fuelwood in both rural and urban areas

of developing countries;

• encourage the development of suitable fuelwood species plantation;

• stepping up the ACP States’ research and development activities as regards the

development of new and renewable energy sources;

Special action concerning associated countries:

• • a special initiative to promote the process of approximation of Community

legislation on renewables in associated countries;

• • implementation of Protocols concerning the participation of associated countries

in promotional EU programmes such as ALTENER;

• • involving associated and third countries in demonstration programmes under the

5th RTD Framework Programme, in addition to specific energy policy

programmes such as SYNERGY and ALTENER;

38

Today, an estimated 2 billion people worldwide lack access to modern energy sources.

Photovoltaics technology is now cost-effective in stand-alone power applications remote fom utility

grids.

24

2.4 Strengthening co-operation between Member States

For successful implementation of the European Union Strategy and Action Plan for

renewable energies, effective co-operation between Member States is of paramount

importance. At present serious discrepancies persist in levels of advancement both

as regards renewable energy implementation in the different Member States, and

between the technologies themselves. Co-operation within a Europe-wide

implementation strategy offers considerable added value to Member States, as

successful policies and experiences at national level can be shared, and national

renewables goals better co-ordinated, with the result that the efficiency of overall

policies as well as particular projects will increase.

The Commission adopted on 4 October 1996 a proposal for a Council Decision

concerning the Organisation of Co-operation around Agreed Community Energy

Objectives

39

. The draft decision identifies the promotion of renewable energy

resources as one of the agreed common energy objectives and calls for supportive

measures at both Community and national levels with the aim of achieving a

significant share of renewables in primary energy production in the Community by

2010. Concrete measures will be proposed as part of the implementation of the

Council Decision, once adopted.

2.5 Support Measures

2.5.1 Targeted Promotion

The ALTENER II

40

programme, and the subsequent programme included in the

proposed Energy Framework Programme

41

will have a crucial role to play as the

basic instrument for the Action plan.

ALTENER II will continue to support the development of sectoral market strategies,

standards and harmonisation. Support will be given to RES planning at national,

regional and local levels and to information and education infrastructures. Support

will also be given to the development of new market and financial instruments.

Dissemination of information is also a major action in ALTENER II. In addition,

promotion of innovative and efficient renewable energy technologies and

dissemination of related information are also supported by JOULE-THERMIE.

In order to enhance the impact of ALTENER II in RES market penetration, new

measures to help overcome obstacles and increase operational capacity for the