Alison Wallace and Julie Rugg

Centre for Housing Policy

Spring 2014

Buy-to-let

Mortgage Arrears:

Understanding the factors that influence

landlords’ mortgage debt

2

About the University of York

York has become one of the top ten universities in the UK for teaching and research. In the Times

Higher Education world rankings of universities less than 50 years old it is first in the UK and seventh

in the world.

There are now over 30 academic departments and research centres and the student body has

expanded to nearly 16,000. Virtually all our research is “internationally recognised” and over

50% is “world-leading” or “internationally excellent” (Research Assessment Exercise 2008). The

University of York is consistently a top 10 UK research university and attracted over £200 million of

funding in the academic year 2011/12. The University works with public, private and third sector

organisations across its research activities.

About the Centre for Housing Policy

The Centre for Housing Policy at the University of York has a twenty-year record of academically

excellent and policy-relevant research, with measurable impacts on policy and services. Researchers

have internationally recognised expertise across the full range of housing issues, and skills

from analysis of large-scale data sets to interviewing vulnerable people. The Centre undertakes

independent, evidence based research for Government departments, charities, and private sector

organisations.

For further information about CHP see www.york.ac.uk/chp

About the authors

Alison Wallace is a Research Fellow and joined the Centre for Housing Policy at the University

of York in 2001. Her expertise is in homeownership and housing markets and, prior to joining

academia, she worked as a social housing practitioner in London.

Julie Rugg is a Senior Research Fellow and joined the Centre for Housing Policy in January 1993.

She has completed work including qualitative research on welfare and its impact on claimant and

landlord behaviour, aspects of the private rented sector and young people’s housing biographies.

© Lloyds Banking Group

3

About Lloyds Banking Group

Our vision

To be the best bank for customers. Becoming the best bank for customers means being the best bank

for businesses, for shareholders, for our people and for our communities.

Our strategy

We will put our customers at the heart of everything we do. We are already re-shaping our business

so that by working together we can focus all our future decisions around our customers. The investment

the Group is making is considerable and will have far reaching benefits in expanding products and

capabilities for our customers – including finding new and innovative ways to help homebuyers. As

a result, we are very pleased to be supporting research in this area. The recently announced Helping

Britain Prosper Plan is designed to make a visible difference for all our customers and within our

communities.

Our brands

The Group operates the UK’s largest retail bank and has a large and diverse customer base. Services

are offered through a number of recognised brands including Lloyds Bank, Halifax, Bank of Scotland,

BM Solutions and Scottish Widows, as well as a range of distribution channels including the largest

branch network in the UK.

BM Solutions is one of the market-leading specialist lenders providing support to the buy to let sector.

Our main aim at BM Solutions is to provide awardwinning service, forward-thinking technology and

competitive products.

Helping homebuyers

As the leading lender to homebuyers across the country, the private rental sector is a core focus for

Lloyds Banking Group. In addition, we helped more than 80,000 first time buyers to purchase their

first home, advancing mortgages totalling over £9.7 billion to these buyers during 2013. Through

our participation in government schemes such as Help to Buy we are providing strong support for the

recovery in the housing market, by facilitating access to mortgage financing for creditworthy home

buyers at up to 95 per cent of property purchase values.

Find out more

Please email [email protected] or call 020 7356 2189 and we will be

pleased to tell you more about our work.

4

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the people who helped us by providing research contacts, data

and access to landlords: Mark Alexander, property118.com; Vanessa Warwick, propertytribes.com;

Tom Entwhistle, landlordzone.co.uk; Wendy Alcock, moneysavingexpert.com; Mark Long, BDRC

Continental; Julie Norris, Bristol City Council; Vicky Watts, Sunderland City Council; and Jennifer

Marlew, Wigan Council.

We are very grateful to all of the lenders, landlords and their advocate organisations who gave time

to talk to us about their experiences and perceptions of the buy-to-let market and landlord mortgage

debt within it.

David Rhodes at the Centre for Housing Policy provided assistance with the quantitative analysis,

and Nicola Moody and Atholynne Lonsdale at the Centre helped prepare the report and provided

office support.

Lloyds Banking Group commissioned the report and we would like to acknowledge the support and

contribution made by Michael Vennard and his colleagues; and of Kate Webb and her colleagues

at Shelter for comments on an earlier draft.

The cover photo is licensed for use by the Press Association.

5

Contents

About the University of York ........................................................... 2

About the Centre for Housing Policy ................................................ 2

About the authors .......................................................................... 2

About Lloyds Banking Group .......................................................... 3

Acknowledgements ........................................................................ 4

Forewords..................................................................................... 6

Executive Summary ........................................................................ 9

1: Introduction ............................................................................. 11

2: Buy-to-let and landlords’ finances ............................................. 13

3: Evidence from the English Housing Survey Private

Sector Landlords Survey 2010 .................................................. 27

4: Lender Loan Book Data Analysis ............................................... 47

5: Landlords and lenders’ experiences of buy-to-let

mortgage arrears .................................................................... 65

6: Summary, discussion and conclusions ........................................ 87

References .................................................................................. 91

Appendix 1: Research Methods .................................................... 95

Appendix 2: Landlord Topic Guide ................................................ 97

Appendix 3: Lender Topic Guide ..................................................101

6

Forewords

Lloyds Banking Group

Lloyds Banking Group is one of the biggest providers of Buy-to-Let mortgage finance in the UK,

primarily through the Birmingham Midshires brand. Buy-to-Let mortgages have been available for

nearly 20 years, and as demand for private rented property grows, deeper understanding of the

market is becoming ever more important.

To aid this understanding we have commissioned this report, in partnership with Shelter, because

there is little research available specifically exploring the issues that cause landlords to default on

their mortgage.

There are clear lessons within this research for landlords, legislators and lenders that can be used to

improve the private rental sector for all.

Potential landlords need to understand their market and treat the letting proposition as a business.

For the best chance of being successful, they should have a clear business plan and ensure they have

enough resources to cover events that cause financial stress – such as repairs and voids.

Legislators must review the obstacles preventing Landlords from getting their property back where

rent isn’t being paid. Small scale landlords often do not have large reserves to draw upon in order

to pay for mortgage payments and maintenance when a tenant stops paying the rent.

A balance clearly needs to be struck to ensure rogue landlords don’t abuse the system, but faster

court processes to enable landlords to evict non-paying tenants are needed before landlords will risk

entering into longer-term tenancies that some tenants want.

Finally the report helps answer some of the questions lenders will have when called upon to look at

lending policies. It clearly demonstrates that tenant circumstances alone rarely cause landlords to

default. In fact, it shows most make as much effort as owner-occupiers to keep their hard-earned

property, often subsidising payments from other income.

Lenders can help by engaging with Landlords, Government and organisations like Shelter in order to

ensure mortgage conditions and processes support a strong and vibrant private rental sector whilst

still delivering the risk mitigation required.

At Lloyds Banking Group we recognise our customers are both landlords and tenants, and believe this

research provides some of the answers to help us deliver Buy to Let mortgages that are appropriate

for the changing market for private rental properties.

Stephen Noakes

Home & Lifestyle Director

Lloyds Banking Group

7

Shelter

Spiralling house prices and the shortage of social housing means that private renting is increasingly

the only option for low and middle income families unable to afford a home of their own. In the long

term we must build the homes Britain needs – including genuinely affordable homes – but in the

interim we must urgently fix private renting for the millions of ordinary people who will be renting

for the foreseeable future.

Alongside ensuring that the Private Rented Sector is genuinely affordable, it is critical that we also

make it more stable. Shelter has proposed the Stable Rental Contract, a five year tenancy model

that provides predictability for renters and landlords alike. We would like to see the Stable Rental

Contract as the mainstream offer for most private renters; however, practices in the buy-to-let market

are still based on yesterday’s private rented sector, usually stipulating a maximum twelve month

tenancy. We welcome Lloyd’s decision to commission this report to deepen understanding of the

challenges of altering current industry norms. By demonstrating a lack of any significant relationship

between landlord arrears and tenancy length we hope this report will instil confidence in the lender

community and enable longer-term tenancies to become more widely available.

Although investigating arrears and tenancy lengths is where this report started, its scope quickly

expanded to consider the general question of what causes buy-to-let mortgage arrears. Stability for

renters requires a secure and stable market because even when families have the stability of a longer

tenancy, landlord mortgage arrears could mean eviction and the loss of their home.

Given the greater role the private rented sector is expected to play in years to come, the report does

not always make for comfortable reading. Its examination finds worrying levels of inexperience in

many parts of the buy-to-let market, with significant numbers of “have-a-go” landlords with poor

business plans and limited resilience to financial shocks. With an interest rate rise in the near future

almost certain, we should all be concerned about the knock-on effect this could have on private

renters.

This report also finds no clear relationship between accepting tenants in receipt of housing benefit

and landlord mortgage arrears. It demonstrates that the rental market has the capacity to rely

on perception rather than robust business sense. In a climate where some landlords have made

headlines by refusing to accept those who use housing benefit to pay all or part of their rent, it is

those renters who need a safety net who will lose out from misconceptions about the risk of arrears.

We all have an interest in improving private renting. Lenders have a role to play as they set the terms

and conditions of their mortgage products and their business practices, which should reflect genuine

risks and rigorously ensure landlords’ ability to repay. By taking the lead, Lloyds have demonstrated

their commitment to playing their part and provided an example to the rest of the sector to follow.

Campbell Robb

Chief Executive

Shelter

8

9

Buy-to-let Mortgage Arrears:

Understanding the factors that influence

landlords’ mortgage debt

Executive Summary

Buy-to-let mortgages underpinned the expansion of the private rented sector, which in the 2000s,

brought in a range of new small sideline investors. The private rented sector now plays a critical role

in the housing market, accommodating excess demand from social renting and homeownership.

This new role has prompted calls for improvements in the quality and management of the sector

and for greater security for tenants who wish to stay long term. This is the first study to examine the

factors that lie behind buy-to-let mortgage arrears, which have the potential to increase the churn

of properties and landlords and thus undermine stability in the sector. It is based upon analysis of

survey data, loan book data and in-depth interviews with landlords and lenders.

Key findings

• The stock of mortgage arrears in the buy-to-let sector is lower than in the residential market but

annual possessions in the buy-to-let market are slightly higher. Lenders have a greater appetite

to move to possess in the buy-to-let market as the property is not the borrowers’ home and the

market is unregulated.

• Landlords are more affluent than the wider population but there are indications that a minority of

landlords have precarious finances. Over a fifth of landlords in the 2010 English Housing Survey

Private Landlords Survey (EHS-PLS) reported problems with their mortgage costs. Three per cent

of buy-to-let loans in the lenders’ data were one month or more in arrears in September 2013.

There was evidence of landlords subsidising their rental property or portfolios to manage or

avoid mortgage debt. While this indicates a strong commitment to the loan it also suggests that

landlords’ financial stress goes beyond the official arrears and possession figures.

• The ability of a landlord to meet their buy-to-let mortgage commitments are challenged by

events arising in the market- tenant demand, rental income, house prices; from the business - the

effectiveness of lettings, rent collection, property management; and from policy - changes to

housing benefit or regulation, for example.

• Through the recession 2008-9 rents dropped, tenant arrears rose, void periods increased and

house prices fell. Change was not uniform and market conditions deteriorated less and recovered

the fastest in the southern regions of the UK. There is therefore an imbalance in the regional

distribution of buy-to-let arrears.

• The most significant factors that increased the odds of a landlord reporting problems with their

mortgage costs were letting property in the North East, and reporting problems with finding

builders, tenant damage, local housing benefit administration, deposit disputes and asking

tenants to provide a reference. These are indicators of letting in difficult markets and problems

relating to the operation of the business. These factors account for a quarter of the variance of

landlords reporting problems with their mortgage costs.

• The factors most likely to increase the odds of loan accounts being one month or more in arrears

were: single applicants, letting a flat, high current loan-to-values, having multiple loans, negative

equity and taking out the loan during the period 2006 to 2008, letting property in the North

East, London and in Northern Ireland. The influence of these factors on the incidence of buy-to-let

10

mortgage arrears was shallow and overall only explained nine per cent of the observed variation

between the loan accounts. These factors are also likely to reflect other attributes associated with

the exuberance of letting at the peak of the housing market.

• Lenders and regulators conceive of buy-to-let as a business but it is not always operated as such.

Market and policy risks become more apparent in weaker housing markets where landlords must

demonstrate more proficient business skills to sustain their property or portfolio. Stronger markets

are more forgiving to landlords who have, or had, less business-orientated approaches to their

letting activities.

• Across all markets adverse events in landlords’ personal and/or financial lives also contribute

substantially to the incidence of buy-to-let mortgage arrears.

• Some professional landlords successfully let properties to tenants in receipt of housing benefit, but

this sector demands a different skill set and more intensive management.

• The 2009-2010 EHS-PLS data does not associate housing benefit paid directly to the tenant with

tenant arrears, but interviews for this study found problems with tenants not passing on housing

benefit or claiming incorrectly. This had contributed to some landlords’ mortgage arrears but did

so in the context of difficult markets and/or limited experience.

• Lenders were also complicit in supporting poor investments, notably at the height of the market

prior to the financial crisis. Lenders with more prudent approaches to the buy-to-let market have

fewer arrears, and after 2008 lenders were adopting a cautious approach.

• However, by pursuing a mainstream part of the market lenders potentially could undermine the

ability of the private sector to house a wide range of households, including those on housing

benefit. However, there were indications that policy changes in this area combined with the

availability of alternative financially robust tenants in some markets exerted a greater influence

over whether landlords let to all tenant groups than lender practices.

• Financially insecure landlords may undermine the ability of the market to deliver a stable secure

and sustainable private rented sector. Lenders have great leverage in supporting these wider

ambitions for the sector. This would entail paying greater attention to appraising the sustainability

and proficiency of landlords to manage in their local markets during mortgage applications.

11

1: Introduction

Summary

• The private rented sector now plays a critical role in the housing market, accommodating

excess demand from social renting and homeownership.

• The sector has expanded substantially over the last decade, but to fulfil its greater role in

the housing market there are calls for private renting to be made more secure, stable and

professional

• Buy-to-let mortgages have contributed to the expansion of the sector and now lenders are

under pressure to permit landlords to offer longer term tenancies and accept tenants on

housing benefit.

• This research examines the factors that may undermine landlords’ finances and present risks

to buy-to-let mortgages to inform future policy discussions.

Background

The private rented sector is an essential component of the UK housing system, performing a wide

range of crucial roles that complement and underpin the operation of both the owner occupied

and the social rented housing sectors, in addition to providing accommodation of ‘first choice’

to many households. The sector has expanded substantially over the last decade, but to fulfil its

greater role in the housing market there are calls for private renting to be made more secure, stable

and professional. The Government has produced a model long-term tenancy for the sector and, in

addition, the Opposition propose a national register of landlords. Lenders have provided the finance

through buy-to-let mortgages for the expansion of the private rented sector and are also under

pressure to remove barriers to the introduction of longer term tenancies and to permit landlords to let

to a wider range of tenants, including those in receipt of housing benefit. However, there is a concern

that the absence of a robust understanding of the factors related to landlord mortgage arrears may

prohibit innovation in the market, and may limit the support that lenders can offer. These policy

discussions will be informed by a precise understanding of risks in the market.

Overall, more than one half of private rented sector dwellings in England were acquired with a

mortgage. Private individual landlords, which are the most common type of private landlord, were

the most likely to have purchased their property, and they were also the most likely to have used a

mortgage to do so. Buy-to-let mortgages were introduced by the Association of Residential Letting

Agents (ARLA) in 1996, and now form an increasingly important part of the mortgage and housing

market. Following the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 there were concerns about the commitment

and sustainability of buy-to-let landlords, however, the market recovered remarkably well. Lending

to first time buyers increased slightly during 2013, which has the potential to undermine demand

for private renting and subsequently the buy-to-let market. However, constrained access to social

housing is likely to remain and the chronic undersupply of homes means that the private rented

sector will retain its new role in the UK housing system for the immediate future.

The buy-to-let and residential mortgage markets have shown different patterns in respect of mortgage

default during this market downturn, as possessions have reduced steadily in the residential market

but have largely been increasing in the buy-to-let market. Unlike the relatively extensive literature

regarding residential mortgage arrears and possessions, no studies have previously examined the

factors implicated in landlords accruing mortgage arrears. At the outset of the recession the position

of tenants was an urgent policy concern as tenancies were brought to a premature close due to the

landlords’ mortgage default, although legislation was introduced to overcome this issue for qualifying

tenancies. And yet, the private rented sector has not attracted the same degree of research as other

12

parts of the housing market. In the context of debates about how to remove the volatility from the UK

housing system and develop a stable and secure private rented sector, providing robust accounts of

why a minority of landlords struggle with mortgage payments is timely.

Research aims and objectives

This research aimed to improve the understanding, among lenders and the wider industry, of the

reasons behind landlords’ buy-to-let mortgage arrears and had three key objectives:

1. What factors are related to buy-to-let landlords’ mortgage arrears and possessions?

2. How do lenders and landlords manage the incidence of buy-to-let mortgage arrears and what

influence does the management of buy-to-let mortgage arrears have on the outcomes?

3. What do the findings suggest can be done by lenders and landlords to prevent or mitigate the

impacts on lenders, landlords and tenants of buy-to-let mortgage arrears?

Research methods

The study involved mixed methods and was undertaken in four phases:

1. A quantitative analysis of secondary data using the English Housing Survey Private Landlords

Survey 2010 (EHS-PLS);

2. A quantitative analysis of buy-to-let loan book data supplied by a single lender;

3. In-depth qualitative interviews with eight buy-to-let lenders; and

4. In-depth qualitative interviews with 25 buy-to-let landlords and two landlord representatives.

The English Housing Survey Private Landlords Survey (EHS-PLS) includes approximately 1000

landlords and the data were collected during 2009-2010. It predates some policy and market

changes but provides robust data relating to landlords and their tenants. The lender loan book data

includes details of all loans made by a single lender from 2001 onward and its total of 338,908

loans represents around a quarter of the entire UK buy-to-let loans. The data provides a rich source

of information about the size and location of landlords and their properties, valuations and mortgage

debt. The in-depth qualitative interviews were undertaken between September and December 2013.

The lenders interviewed offered perspectives from around two-thirds of the buy-to-let market. The

landlords were largely drawn from across the UK and were mainly landlords with more than one

property, and comprised a mixture of landlords in arrears, landlords struggling financially and

landlords who had no problems meeting their mortgage commitments.

Further details of the research methods adopted are provided in Appendix 1 and of the topic guides

used in the in-depth interviews in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 provides an overview of buy-to-let arrears as they stood in Spring 2014 and considers what

the existing knowledge base tells us about landlords’ finances and the range of risks and pressures

they face. Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 present the results of the analysis of the English Housing Survey

and the lenders’ loan book data respectively. These analyses provide an overview of the landlords

surveyed and identify the various circumstances associated with landlords experiencing problems

with their mortgage costs and loan accounts that carry mortgage arrears. Chapter 5 reports the

findings from the qualitative in-depth interviews and provides substance to unresolved questions

evident in the quantitative analysis. The final Chapter 6 provides a discussion of the issues raised by

the evidence collected in the study and concludes with some broad recommendations for lender and

landlord organisations to consider.

13

2: Buy-to-let and landlords’ finances

Summary

• The stock of mortgage arrears in the buy-to-let sector is lower than in the residential market

but possessions in the buy-to-let market are slightly higher. Lenders have a greater appetite

to move to possess in the buy-to-let market as the property is not the borrowers’ home and

the market is unregulated.

• The rise in buy-to-let lending reflects the growing confidence among landlords who see many

aspects of the sector improving, although not uniformly.

• The ability of a landlord to meet their buy-to-let mortgage commitments can be challenged

by events arising in the market- tenant demand, rental income, housing prices; from the

business, – the effectiveness of lettings, rent collection, property management; and from

policy, – changes to housing benefit or regulation, for example.

• Through the recession 2008-9 rents dropped, tenant arrears rose, void periods increased

and house prices fell. Change was not uniform and market conditions deteriorated less and

improved the fastest in the southern regions of the UK.

• Landlords are more affluent than the wider population but there are indicators that a minority

of landlords have precarious finances.

Introduction

Much attention is afforded to understanding the risks within homeownership across the economic

and/or housing market cycle, to households, lenders and the state, and how the incidence of

mortgage default can be managed (Policis, 2010; Ford and Wallace, 2009; Gall, 2009; Stephens et

al., 2008; Ford et al., 2001). To date, there has been little focus on how market cycles impact upon

the private rented sector, and in particular how landlord’s behaviour and housing market turbulence

translate into risks to mortgage finance in this part of the housing system. This is a curious omission

as the private rented sector has expanded significantly in recent years, due to tenure shifts produced

from constrained access to homeownership and limited access to social housing. The increased

importance of private renting demands that closer attention is paid towards understanding factors

that could undermine the stability desired in the sector.

Volatility in the UK housing market may overall have lacked the drama of the house price peaks and

troughs experienced most recently in the Republic of Ireland or Spain, for example, but a degree of

instability has been a defining characteristic of the UK housing market since the 1970s, since when

four significant downturns have occurred (Stephens et al., 2008; Stephens, 2011). Internationally, the

incidence of mortgage defaults throughout the market cycle, and in particular during the downturns,

are a consequence of the interaction between the mortgage market, labour market and social

protection offered to mortgage borrowers, as well as changing patterns of household dissolution

(Ford and Wallace, 2010). Consequently, the UK’s residential mortgages are subject to greater risk

of defaults than in, for example, Germany, where arrears are historically very low; or at a lower

risk in comparison to Ireland or the United States (Schaber and Gill, 1999; FSA, 2012). However,

it is uncertain how the changing housing market, the framework of mortgage market regulation,

statutory support for tenants and/or borrowers, the labour market and changing demographics

influence the buy-to-let mortgages that have supported the expansion of the private rented sector.

To begin to fill these knowledge gaps, this chapter provides an overview of existing evidence about

buy-to-let, the incidence of mortgage arrears and possessions in this part of the market and the

various factors that may exert pressure on landlords’ finances.

14

The rise of the private rented sector

The importance of the private rented sector to UK housing policy has never - at least in the post-

war period - been so high, with increasing policy expectations that the sector will take the strain

from constraints in other parts of the housing market (DCLG, 2011a; Whitehead et al., 2012). A

combination of factors, including limitations on first time buyers obtaining mortgages and persistent

problems of affordability of homeownership in many locations, combined with access constraints

to social housing has increased demand in the privately rented sector. Indeed, there has been a

significant restructuring in UK housing tenure over the last two decades. Private renting more than

doubled in size between 1991 and 2011, growing from just over two million dwellings (nine per

cent of the UK stock) to 4.7 million dwellings (17 per cent of the stock). Over the same period, the

owner occupied stock has dropped slightly from 67 per cent of the UK stock to 65 per cent (peaking

at 69 per cent for much of the 2000s); and social rented housing has dropped from 25 per cent to

18 per cent of the UK stock during the same period (CLG Live Table 101).

The origins of buy-to-let mortgage provision in the mid-1990s are well rehearsed, reflecting the poor

external housing market conditions of the 1990s downturn and the under-performance of alternative

asset classes. It was a market response that permitted landlords ready access to mortgage finance

(Crook et al., 2012; Gibb and Nygaard, 2005; CML, 2001; Rhodes and Bevan, 2003). Buy-to-let

therefore underpinned the expansion of private renting. Arguably buy-to-let also met increased

rental demand to which it had itself contributed, as affordability pressures prevented some first time

buyers accessing homeownership and regulatory imbalances gave landlord investors competitive

advantages (Wilcox, 2013; FSA, 2012).

Accompanying the growth in private renting, buy-to-let lending has become an increasingly

important part of the mortgage market, with the number of loans increasing from approximately

73,000 buy-to-let loans outstanding in 1999 to 1.5 million by 2013 (CML Table AP5). The market

share occupied by buy-to-let loans increased from 0.7 per cent in 1999 to 13 per cent by Q3-2013

(CML Table AP7). The value of lending in this sector grew from £3.9 million in 2000 to £15.7 million

by 2012, although this remains at approximately a third of the size of the market at the height

of the market boom in 2007 when £45 billion was advanced (CML Table MM17). The growth in

buy-to-let finance has meant that in 2010 more than one half of private rented dwellings had been

obtained with a mortgage (56 per cent), a proportion that was highest amongst private individuals

(64 per cent), who account for 89 per cent of private landlords within England (DCLG, 2011b). The

importance of mortgage finance to this part of the housing market reinforces the significance of

understanding the threats to these loans.

The rise in buy-to-let lending reflects the growing confidence among landlords who see many

aspects of the sector improving, although not uniformly (BDRC, 2013). However, the expansion of

the sector runs in parallel to greater demands for reform, to increase the professionalism of what

has regularly been described as a ‘cottage industry’ (Rugg and Rhodes, 2008). Both Shelter and

the Building and Social Housing Foundation have recently proposed that policy attention should

be focussed on measures that protect the interests of the increasing proportion of families living

in the sector (Shelter, 2011; Pearce, 2013). Advocates of ‘stable renting’ are seeking changes to

security of tenure, to promote longer tenancies, and some level of landlord registration or licensing.

The Department of Communities and Local Government has worked with industry representatives

and other stakeholders, to produce a model longer-term tenancy, provided tenants with the right to

request longer tenancies from landlords and proposed that letting agents belong to a redress scheme

(CLG, 2013). To reflect these new uses for the private rented sector and policy ambitions there is also

pressure on lenders to revise clauses in the buy-to-let mortgage terms that often limit the length of

tenancy that landlords can offer tenants to 12 months, or that specify categories of tenants to which

landlords cannot let properties. Two large lenders recently reversed previous policies of prohibiting

landlords from letting to tenants on housing benefit and shorter tenancies, but these risks in terms of

lending are poorly understood.

15

Buy-to-let mortgage arrears and possessions

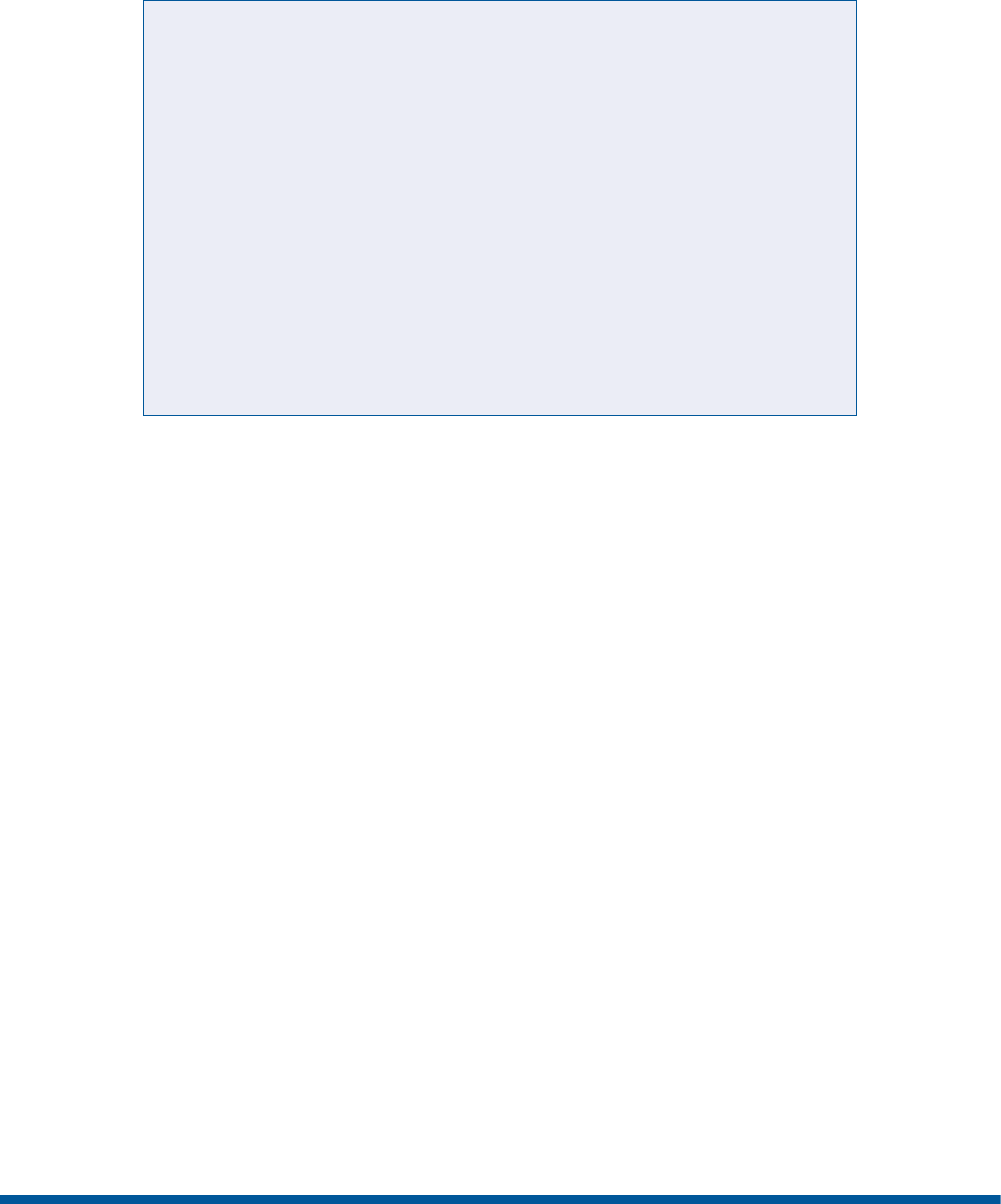

The financial crisis of 2007/8 induced an increase in arrears and possessions across all types

of mortgages, but residential and buy-to-let mortgage arrears have since followed quite different

trajectories. Arrears rose and fell more sharply in the buy-to-let market compared to residential

(Figure 2.1). The rate of possession was initially higher in the residential market but since 2009 has

fallen steadily, compared to the buy-to-let market where there has been additional volatility and up

until 2012 a steady growth in possessions (Figure 2.2). The proportion of all possessions reported

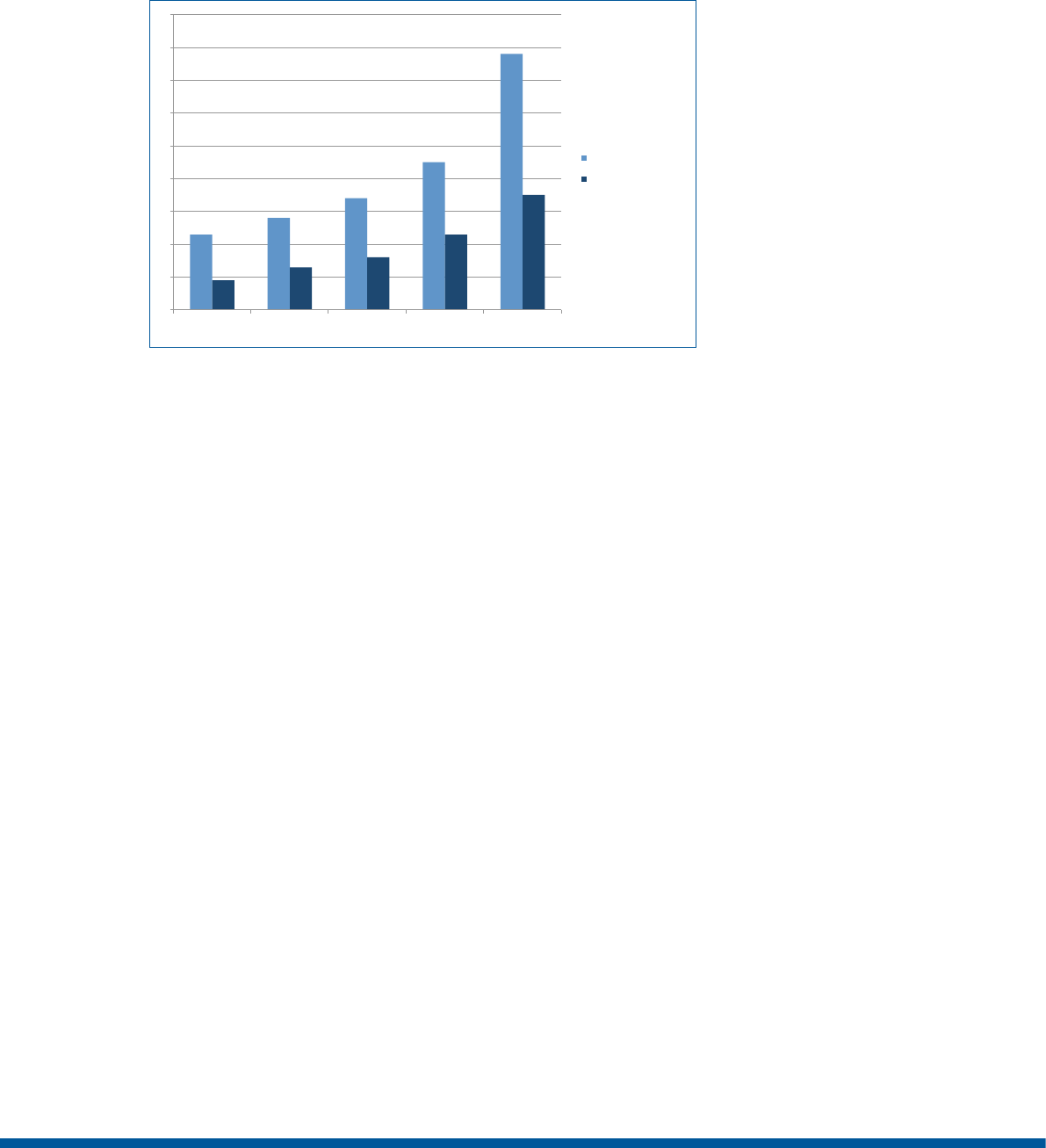

by CML attributable to buy-to-let loans has also grown (Figure 2.3).

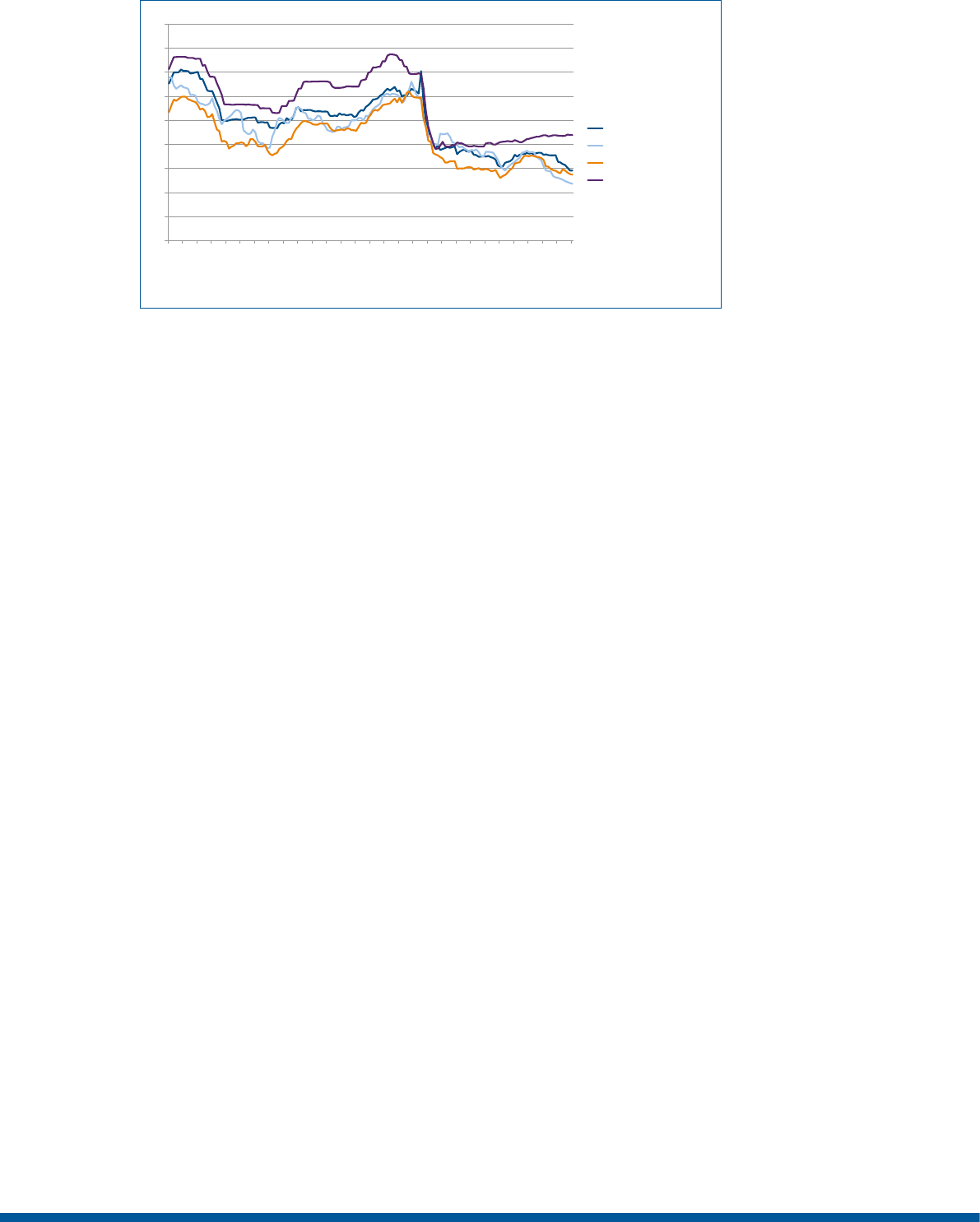

Figure 2.1: Percentage of loans 3 months or more in arrears (%)

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Residential

Buy-to-Let

Source: AP8 CML Statistics NB: Arrears includes loans passed to a Receiver of Rent

Figure 2.2: Percentage of all loans that ended in possession (%)

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

0.14

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Residential

Buy-to-Let

Source: AP7 CML Statistics NB: Possessions include properties sold by Receiver of Rent

16

Figure 2.3: Buy-to-let possessions as a proportion of all possessions (%)

0

5

10

15

20

25

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Source: Table AP8 CML Statistics

As they are commercial loans, lenders are less tolerant of buy-to-let mortgage arrears and do

not apply forbearance in the same manner. Therefore, the duration of arrears on loan accounts is

likely to be shorter than in the residential market. This means comparing buy-to-let and residential

mortgage market data is problematic. The data suggests that there are fewer arrears cases and

higher possessions in the buy-to-let market in comparison to the residential market. However, as

landlords’ accounts in arrears are referred to a receiver of rent

1

or passed through the litigation

process more quickly, this is not necessarily an indication that there is a reduced flow of buy-to-let

loans in arrears, just that the stock of buy-to-loans in arrears at any point in time is smaller.

The buy-to-let mortgage market is also not subject to consumer regulation. Unlike residential loans,

which have been subject to regulation since 2004, buy-to-let loans are not subject to oversight by

the financial services regulator the Financial Conduct Authority (formerly the Financial Services

Authority). Since 2007, the regulator has closely scrutinised the UK mortgage market to ensure

residential lending practices were compliant with the Mortgage Conduct of Business (MCOB) and

Treating Customers Fairly. Earlier light touch principle-based regulation was replaced with a more

stringent regime and a substantial review of the mortgage market undertaken, culminating in

regulatory changes introduced in April 2014. The Mortgage Market Review requires that, among

other things, lenders pay closer regard to the affordability of loans at the point of sale and stress

test affordability for potential interest rate rises (FSA, 2012). Various thematic reviews generated a

great deal of data and analysis relating to the risks in the sector, but these analyses largely omitted

the buy-to-let sector.

The Mortgage Market Review floated the idea of limiting loan-to-values (LTVs) and loan-to-incomes

(LTIs) in the residential market, measures that were subsequently dropped in favour of affordability

checks, although there are indications that counter-cyclical provision in this area may be made to

calm any over-heating markets in the future (FSA, 2010). The FSA analysis did reveal, however, that

only in the buy-to-let market (and ‘other’ loan category) were high LTIs and LTVs of over 90 per cent

associated with higher rates of default (Wilcox, 2013).

1 Law of Property Act Receivers, or Receivers of Rent, act for banks and private lenders who have secured their loans by a Legal Charge

(mortgage) on a property. Under the terms of the Legal Charge the lender can appoint a Receiver to deal with a property when the terms of

the mortgage are not being met – usually when repayments and interest are not being paid. The Receiver assumes management responsibility

of the property, collecting rent and undertaking repairs, and occasionally re-letting the tenancy and passes the rent to the lender to meet the

terms of the mortgage.

17

Landlord financial pressures

There is little existing evidence that informs us about the reasons that landlords have mortgage

arrears, although the growing literature on the sector does provide some insight into the financial

circumstances and pressures felt by landlords. Crook et al. (2012) identify two types of risk to

landlords’ letting activities. Firstly, those arising from the market risks, so once a property has been

purchased the landlord has no further control over the capital values or the rents they can earn.

Obviously tied up with how landlords appraise the properties they purchase at the outset, is the

second set of risks, the business risks, which reflect the skills with which the landlord operates the

day to day management of the property. These activities include choosing tenants, letting tenancies,

collecting rent and organising repairs, for example. These matters are within the landlords’ control.

In addition a third risk may also be apparent as further external factors beyond the landlords

immediate control are regulatory or policy risks. These may arise from local or central government,

and examples would be housing benefit changes or local licensing. There are recursive relationships

between these potential threats to landlords’ finances, but this chapter organises the remaining

literature and data review around these themes.

Market Risks

The key risks arising from the market relate to how the landlords’ property is affected by the local

housing and labour markets as well as the wider mortgage market. Key issues are the sustainability

of rental income, house prices and mortgage costs.

Rental income

Clearly rental income is the key resource that landlords use to meet buy-to-let loan repayments, and

factors that threaten this income stream have the potential to jeopardise the mortgage. Rental income

may be threatened by a drop off in tenant demand for particular property types and/or locations,

raising the possibility of greater vacant periods and declining rents; or by the failure of the tenant to

actually pay the rent due if they become unemployed, for example.

Constrained new supply is a feature of the UK housing system and increased demand for housing

that currently cannot be satisfied in social housing or homeownership, has largely meant higher

tenant demand and some increased rents in the private rented sector. However, this strong tenant

demand was not felt uniformly across the country. Consequently, more landlords were reporting rent

increases in the south of England and London than in the northern regions, Scotland and Wales

(BDRC, 2013). While there does seem to be some disparity regarding the scale of the any rent

increases reflected in the various data sources, the regional differences remain clear. Hometrack

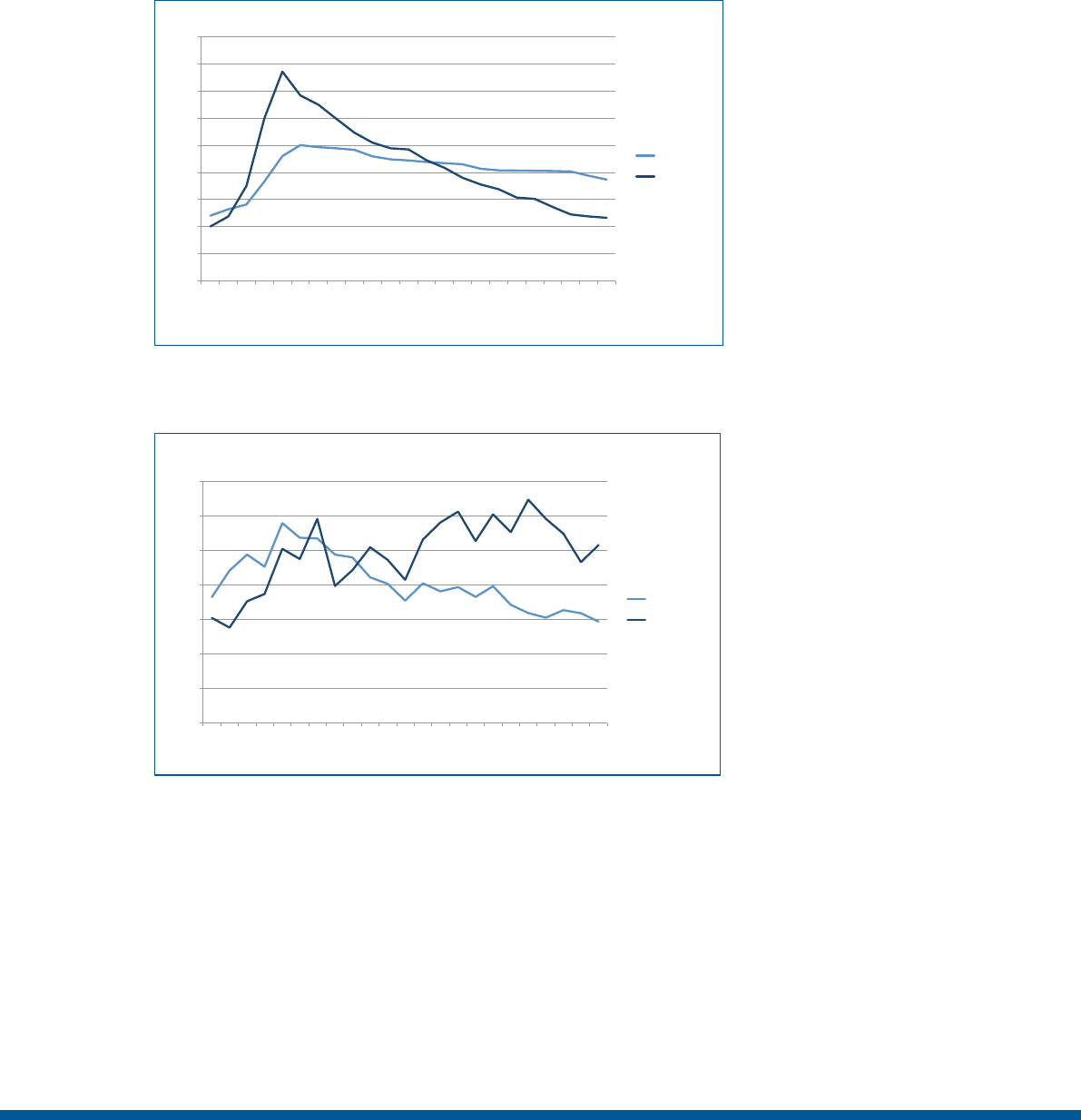

(2013) provide an assessment of changes in rents achieved across the UK (Figure 2.4 and Figure

2.5). Overall rents fell after the onset of the financial crisis but have since recovered, although

outside of London they display greater volatility. Closer analysis of changing rents shows that the

greatest reductions in rents achieved were away from London and the South East, where rents

declined less and recovered faster. Crook et al. (2012) in a study of landlords in Scotland also found

buy-to-let landlords who bought near the height of the housing market and who let in areas where

rents were falling after the credit crunch were experiencing difficulties with loan repayments. We can

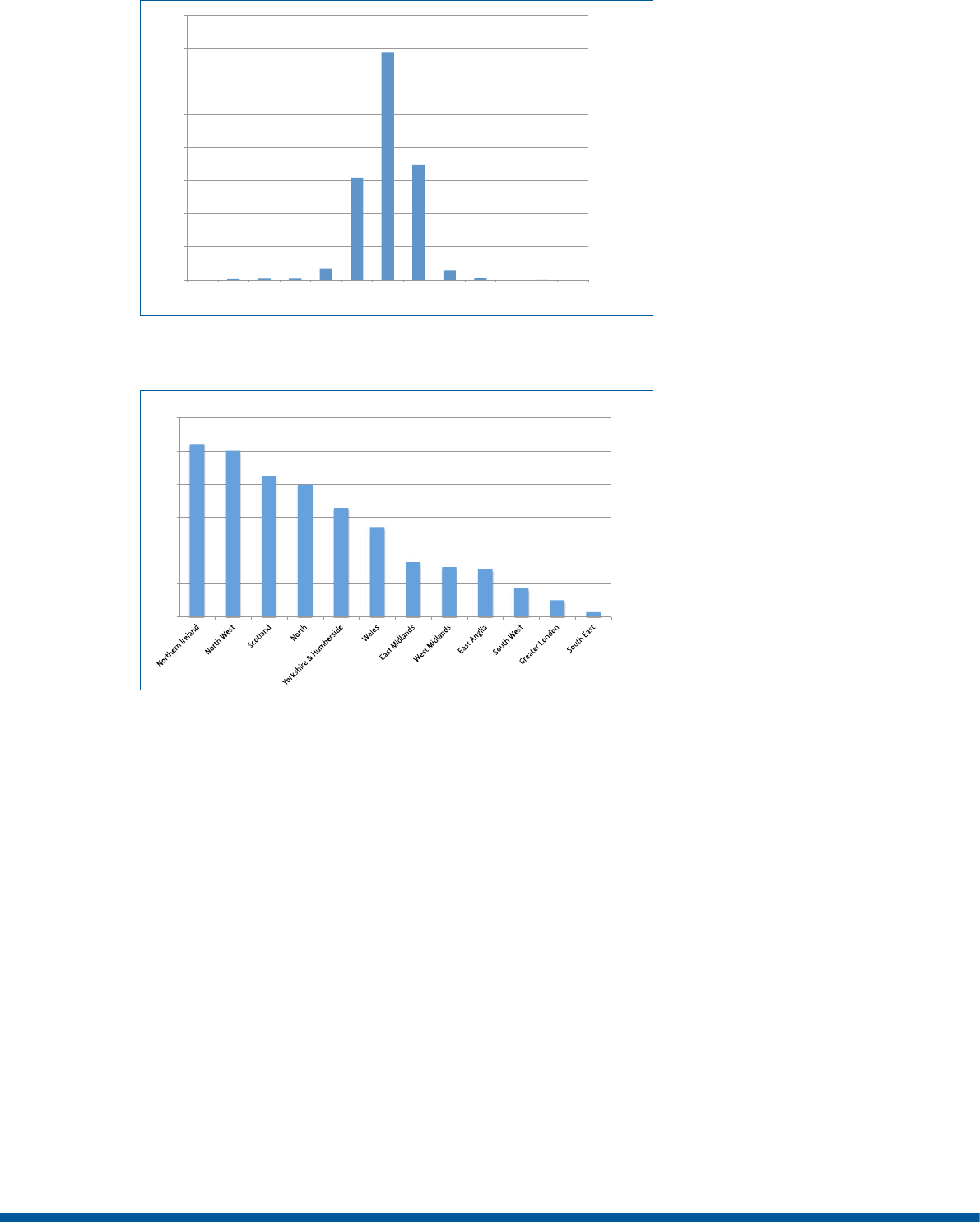

see from the Hometrack data [Figure 2.5] that Scotland experienced the greatest declines in rents

during 2008 and 2009, although it also recovered sharply too.

18

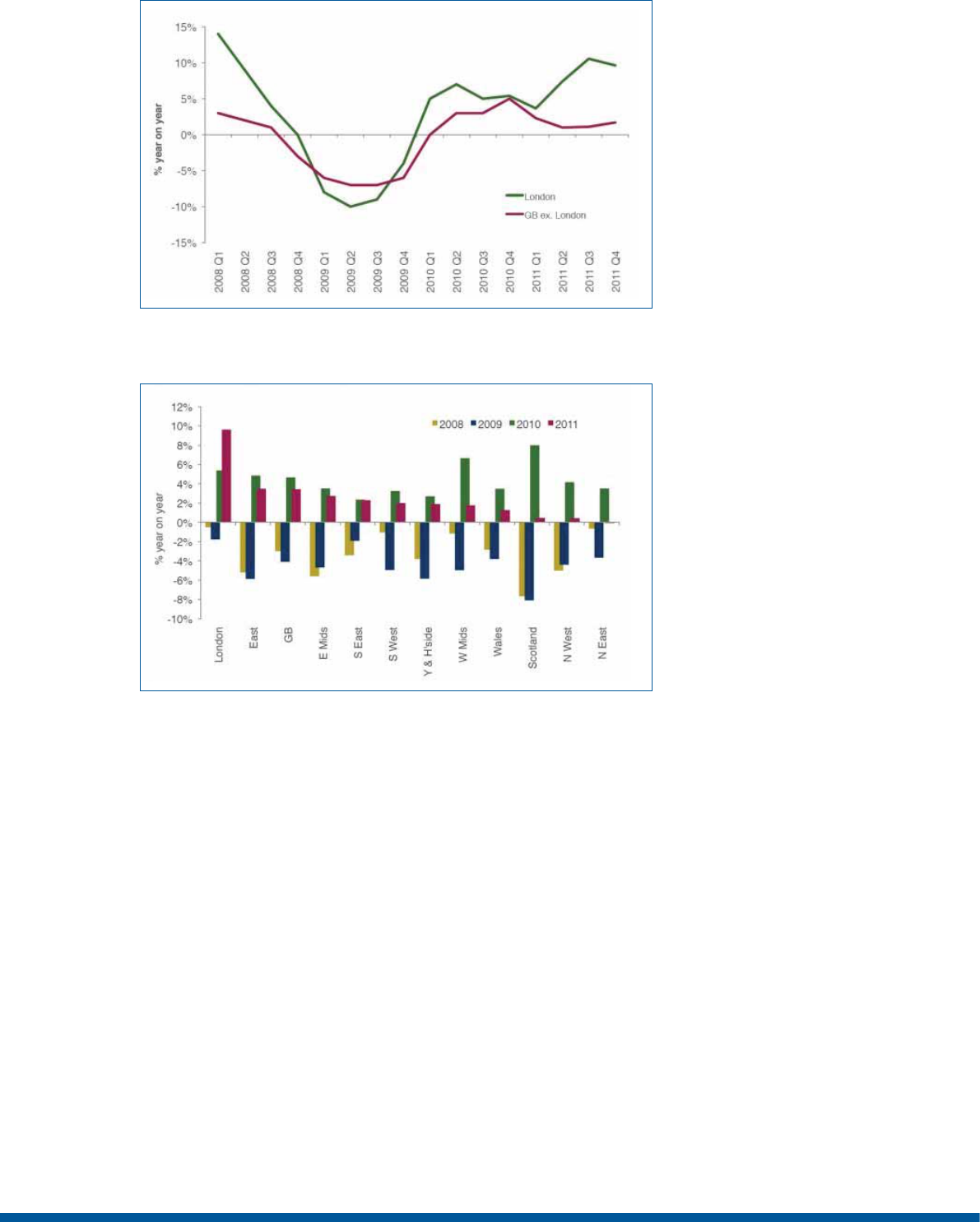

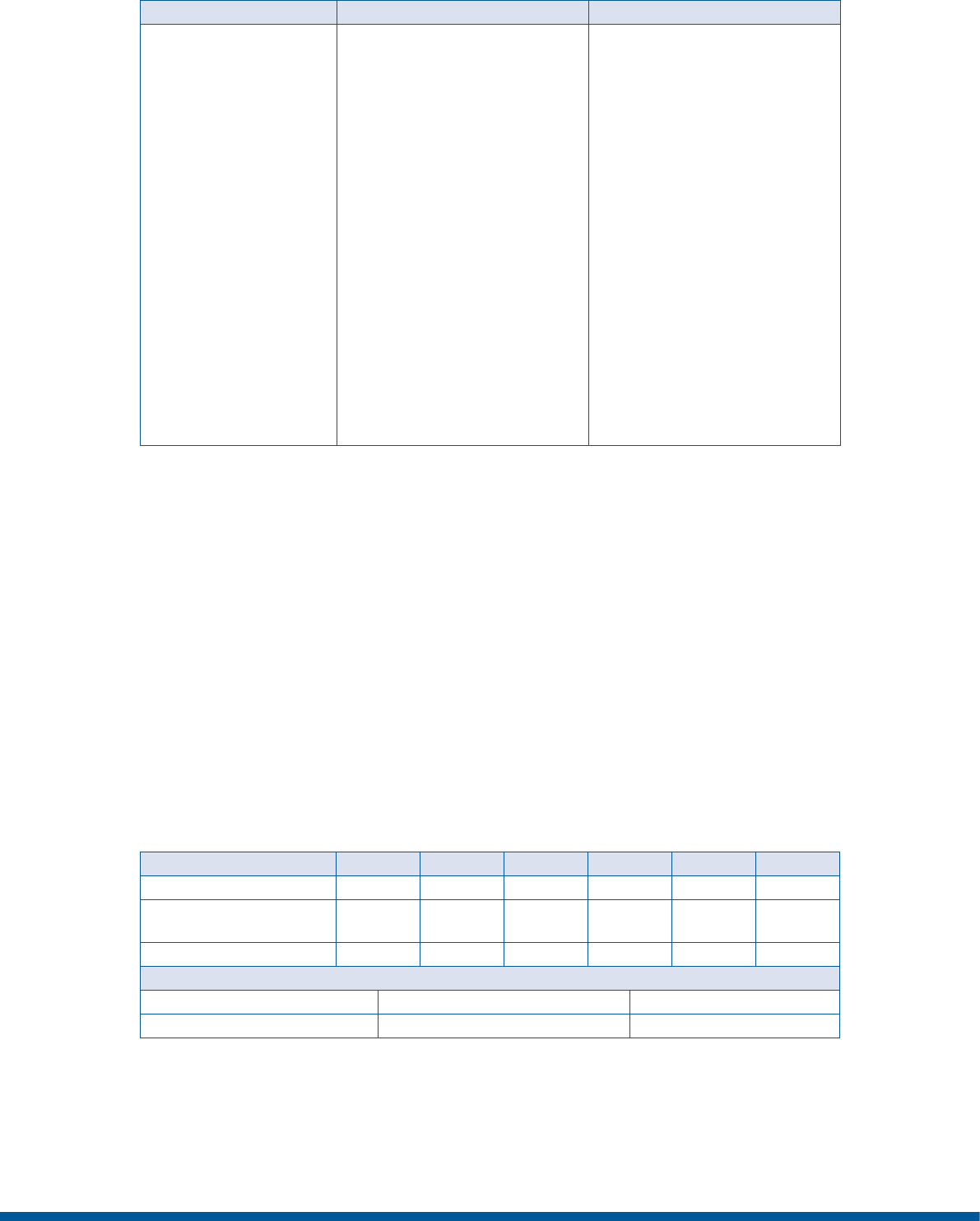

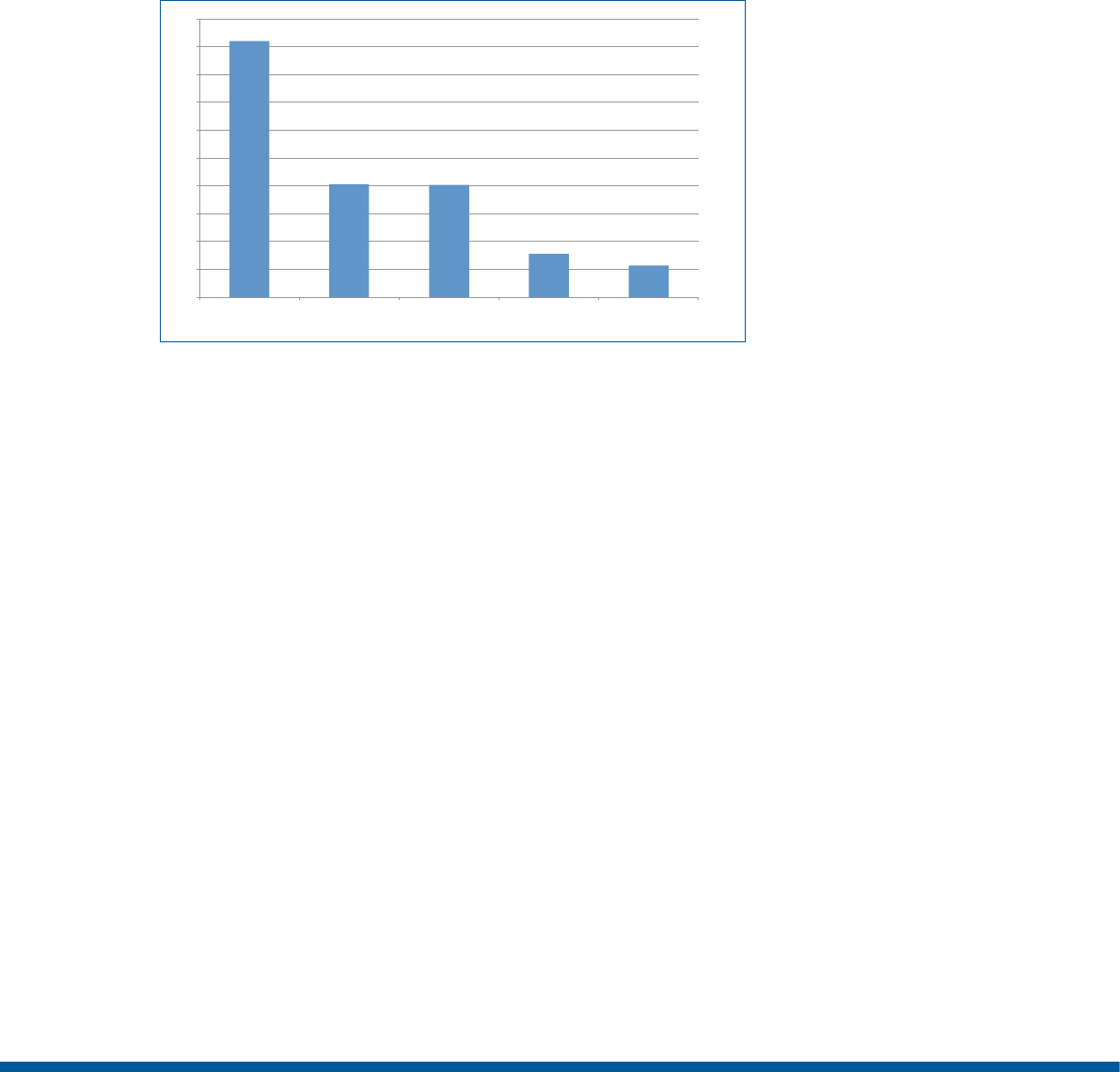

Figure 2.4 Year on year growth in private rents 2008 to 2011

Source: Hometrack (2012)

Figure 2.5: Year on year rental growth by region 2008 to 2011

Source: Hometrack (2012)

Hometrack (2013) also note that rental growth in London was running at minus one per cent in

October 2103, as affordability constraints due to real wages growing less than rents had exerted

a brake on rent rises, as well as the increased availability of mortgage finance which has allowed

some former renters to purchase.

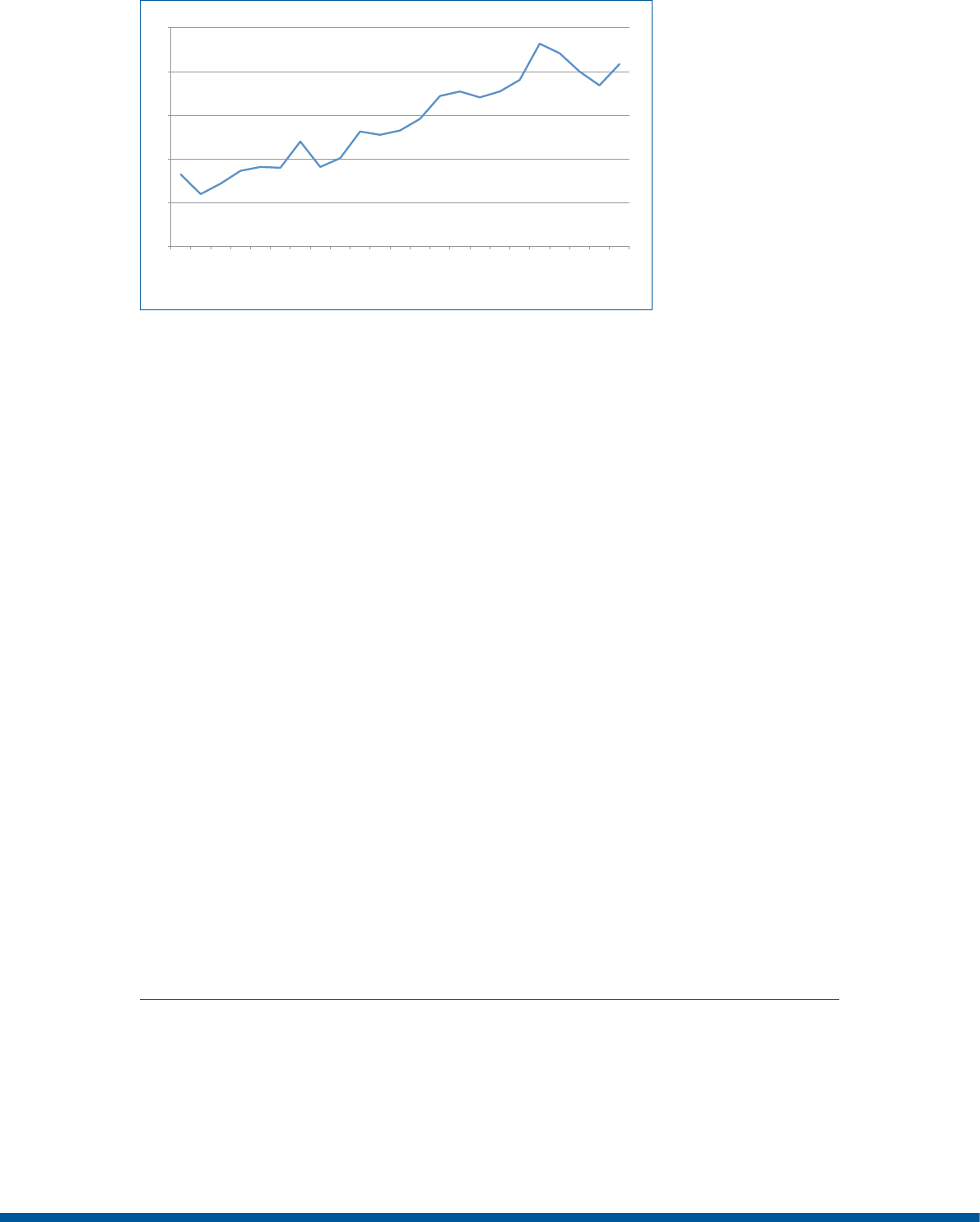

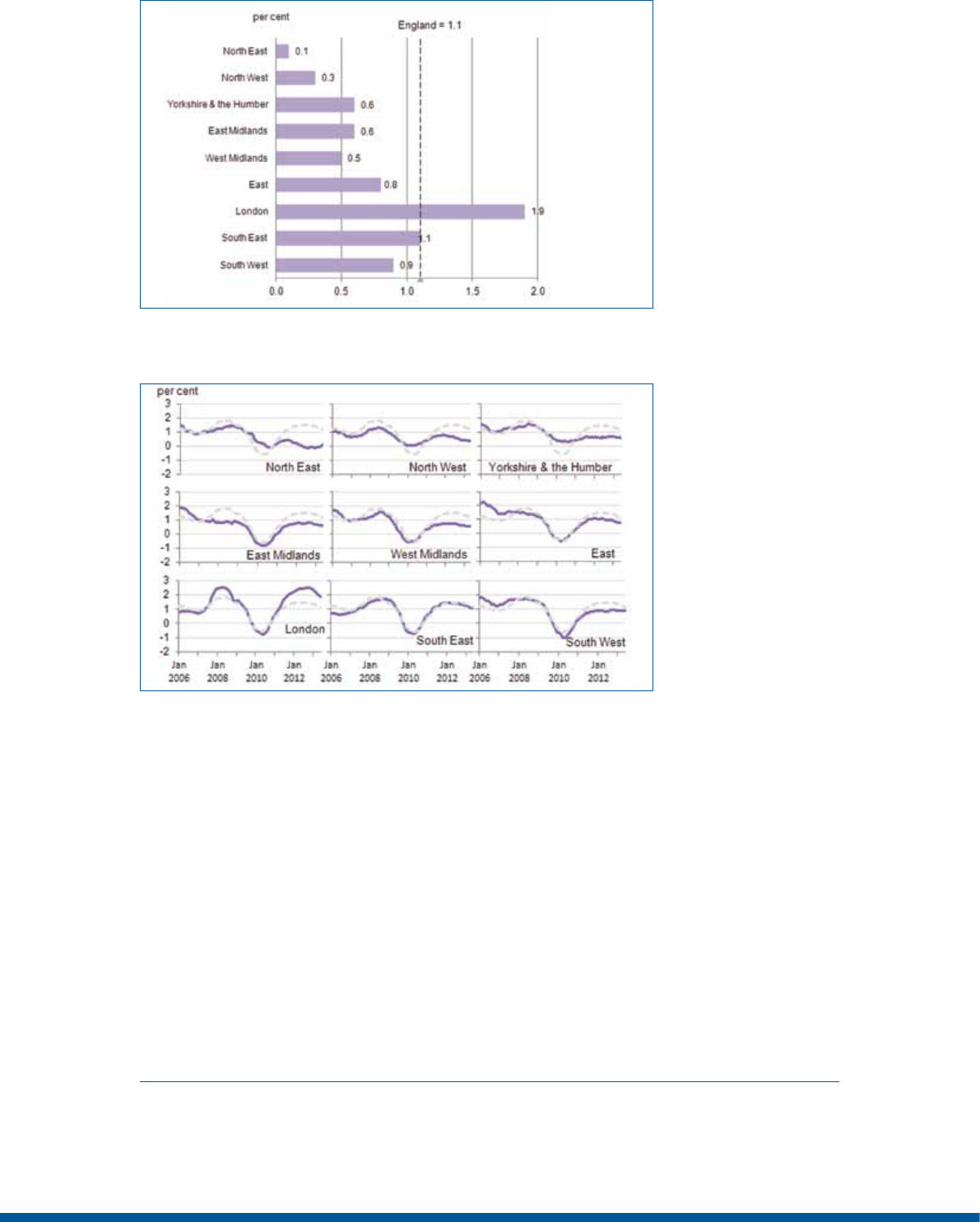

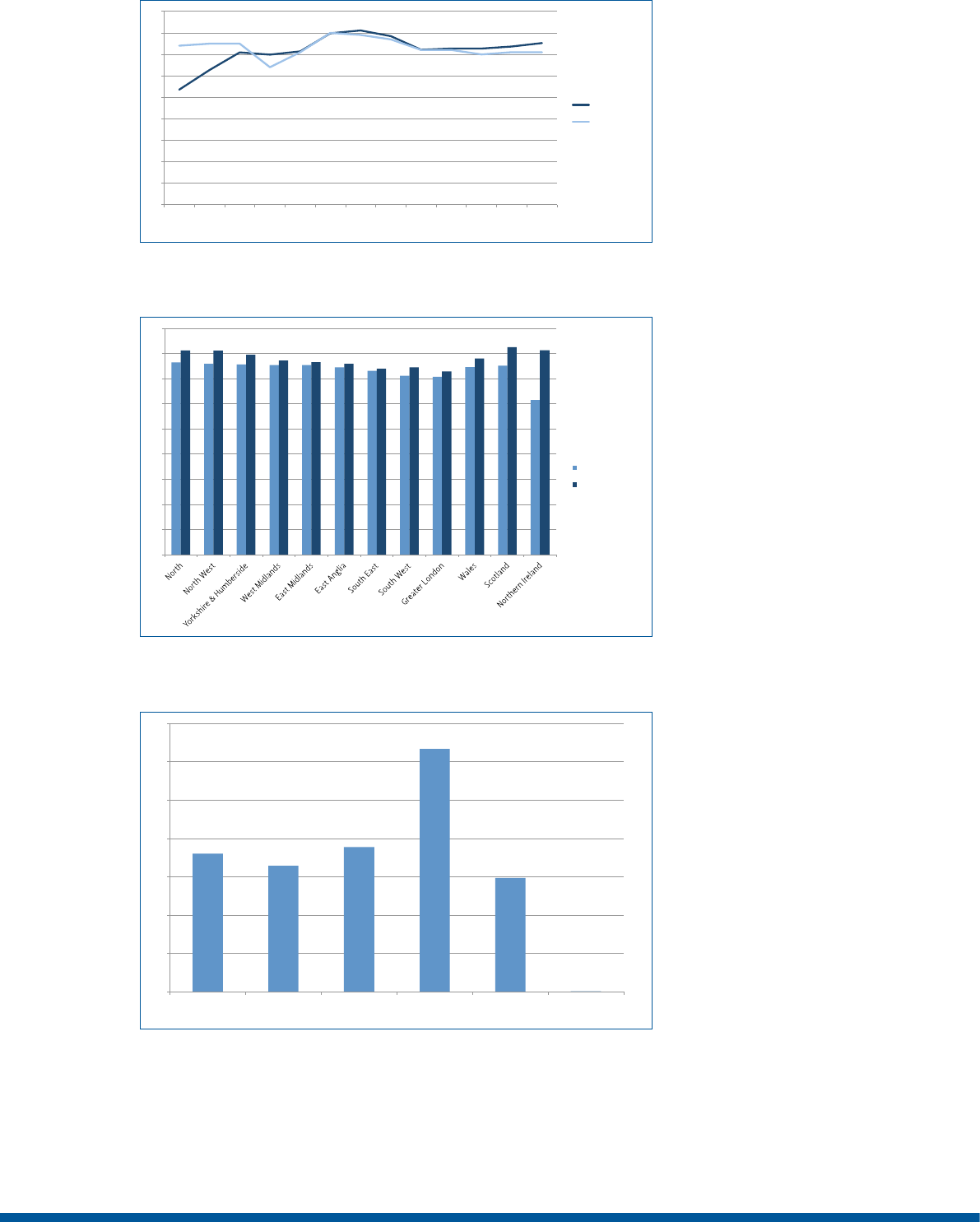

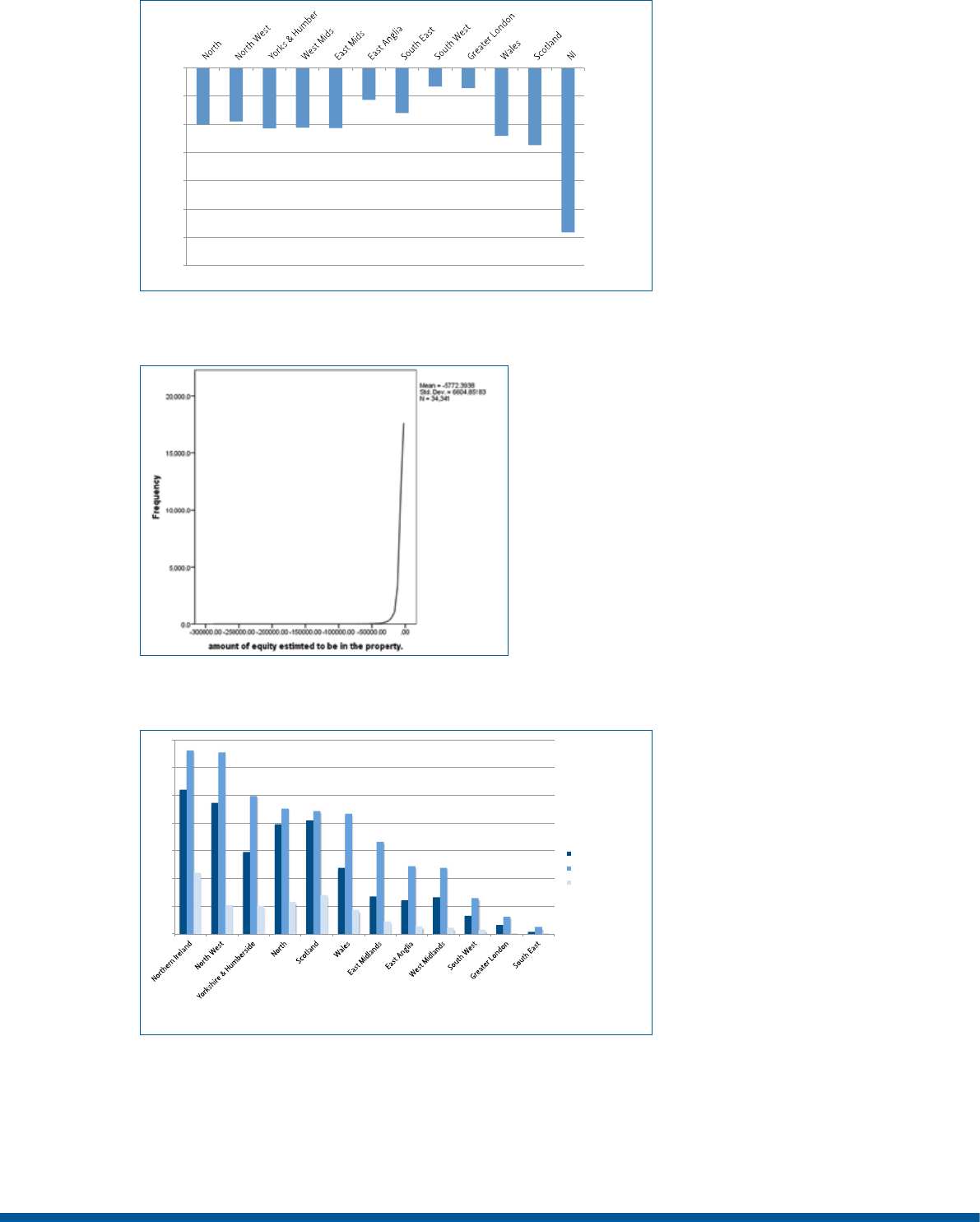

The Office of National Statistics have an experimental rental index that shows the regional disparity

in annual changes in rents by English regions over the last 12 months and between 2006 and 2013

(Figure 2.6 and Figure 2.7) (ONS, 2013). Using these data the significant falls in rental income

since the recession remain pronounced in the northern regions. More recently, despite media reports

of significant rises, any rent increases in the ONS data have been modest, and although more

significant in London, do not seem to reflect a profound change overall.

19

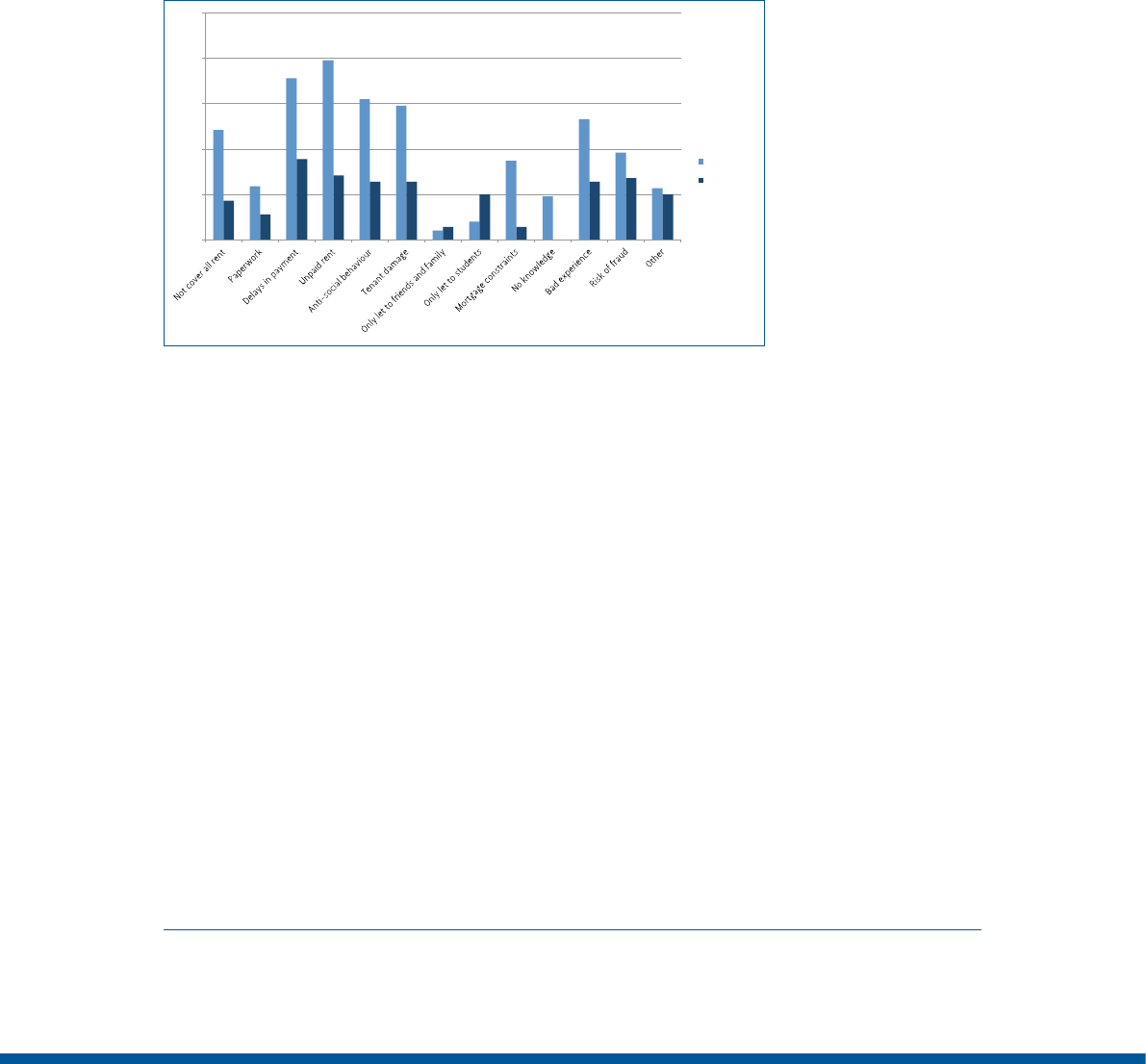

Figure 2.6: IPHRP Change over 12 months by English region August 2012-2013

Source: IPHRP ONS

Figure 2.7: IPHRP Change over 12 months by English region 2006 to2013

Source: IPHRP ONS (darker line=region; broken line= average for England)

Aside from rent levels the propensity of tenants to pay the rent is also intuitively a key influence on

the financial pressures on landlords, but the evidence on tenant rent arrears is slightly unclear. The

ability or willingness of tenants to pay the rent may be influenced by the local economy, and/or

it may relate to policy risks and the ease of obtaining local housing allowance or housing benefit,

which is discussed below.

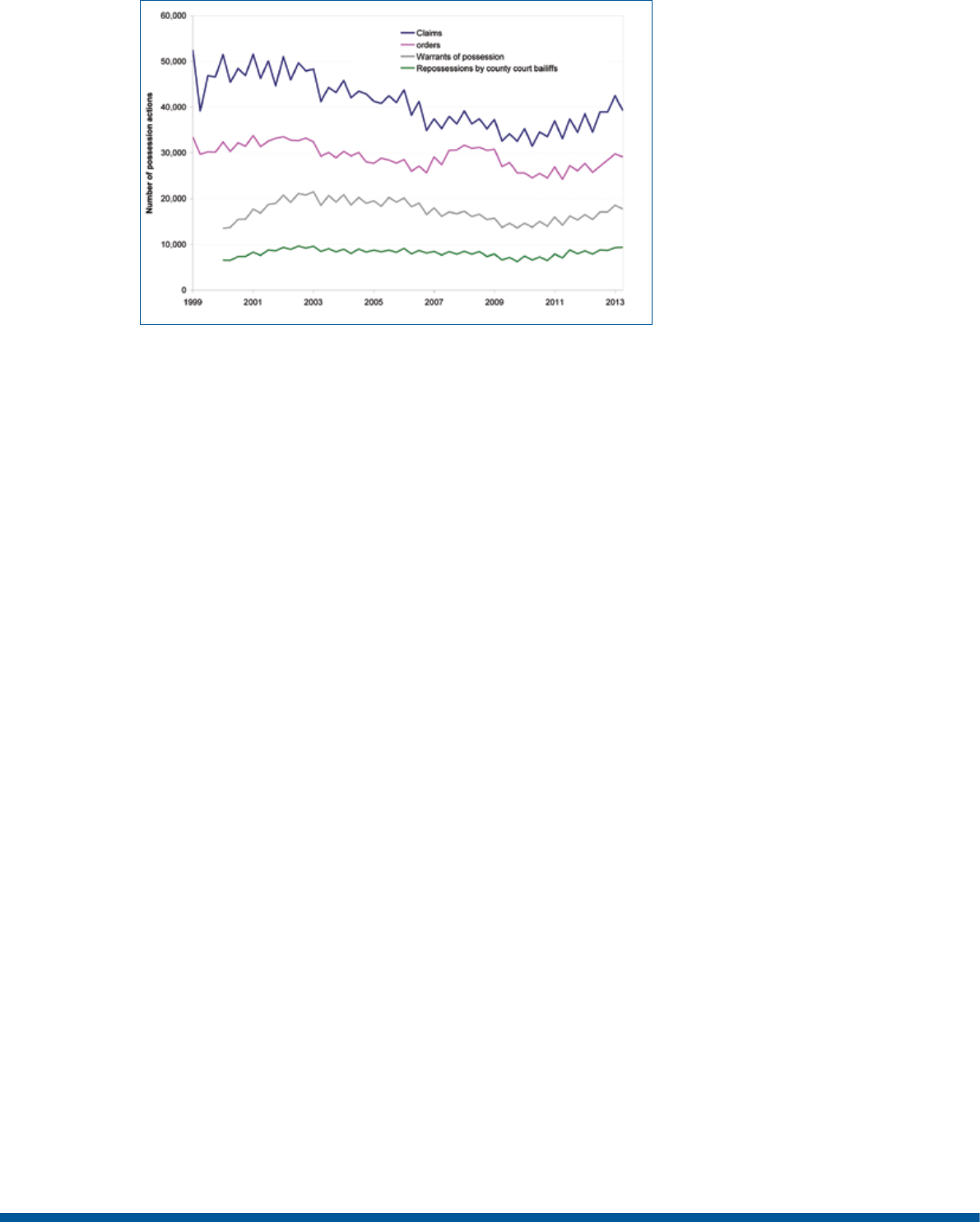

The incidence of landlords seeking possession in county courts on the grounds of rent arrears is an

indicator of trends in this area and represented in Figure 2.8. However, two caveats exist; firstly,

these data include social rented sector landlords as well as private landlords, and secondly, not all

landlords may pursue formal litigation in the county courts as a redress for rent arrears, but choose

to end the tenancy when it expires using section 21

2

(Ministry of Justice, 2013). These data show

that the number of landlord possession claims in County Courts fell during the period 2003 to 2008,

but increased since 2010 by 29 per cent to 45,000 in the third quarter of 2013. This pattern of a

reduction in landlord claims for possession up to 2010 and subsequent rise has been similar across

all regions.

2 Under the Housing Act 1988 Section 21 gives a landlord an automatic right of possession without having to give any grounds (reasons) once

the fixed term has expired.

20

Figure 2.8: Landlord possession claims in the County Courts

Source: Ministry of Justice

Templeton LPA/LSL Property Services also provide a track of private tenants in severe rent arrears-

here defined as two months or more (LSL Property Services, 2013) (Figure 2.9). Templeton/LSL

data shows some volatility, with tenants in serious arrears reaching a peak in 2012 and then falling

subsequently. By Q3-2013 serious rent arrears affected 1.7 per cent of all tenancies, and represented

a fall of 34 per cent from Q3-2012. The LSL Buy-to-Let Index shows the proportion of private tenants

in any arrears at 7.1 per cent in October 2013, which they report as being the lowest since their

records began in 2008 when 13.1 per cent of tenants were in arrears. Similarly, BDRC (2013) report

that the proportion of landlords reporting tenant arrears declined from 63 per cent to 51 per cent

between 2012 and 2013.

Landlord’s rental income is also affected by the number and length of void periods experienced.

Landlords Survey data from BDRC and the National Landlords Association in March 2013 suggests

that a third of landlords had experienced a vacant period within the last 12 months, a decline of

13 per cent from the previous year (National Landlords Association, 2013a). There were significant

regional differences with 54 per cent of North East landlords experiencing voids, compared to only

20 per cent of London landlords.

This aggregate market evidence is mixed but private market data suggests an improving situation

in terms of tenants filling vacant property and meeting rental commitments. What is not clear from

these data, however, is to what extent and how the incidence of tenant rent arrears or voids may flow

into landlords’ mortgage arrears, not least as best practice is to build in void periods and additional

management and maintenance costs to the business model. Moreover, it is also uncertain whether

reductions in tenant rent arrears reflects an increasing ability of tenants to meet their rent as the

economy improves, or a shift in landlords’ letting behaviour in accepting less risky tenants.

21

Figure 2.9: Tenants in two months or more rent arrears

Source: LSL/Templeton LPS

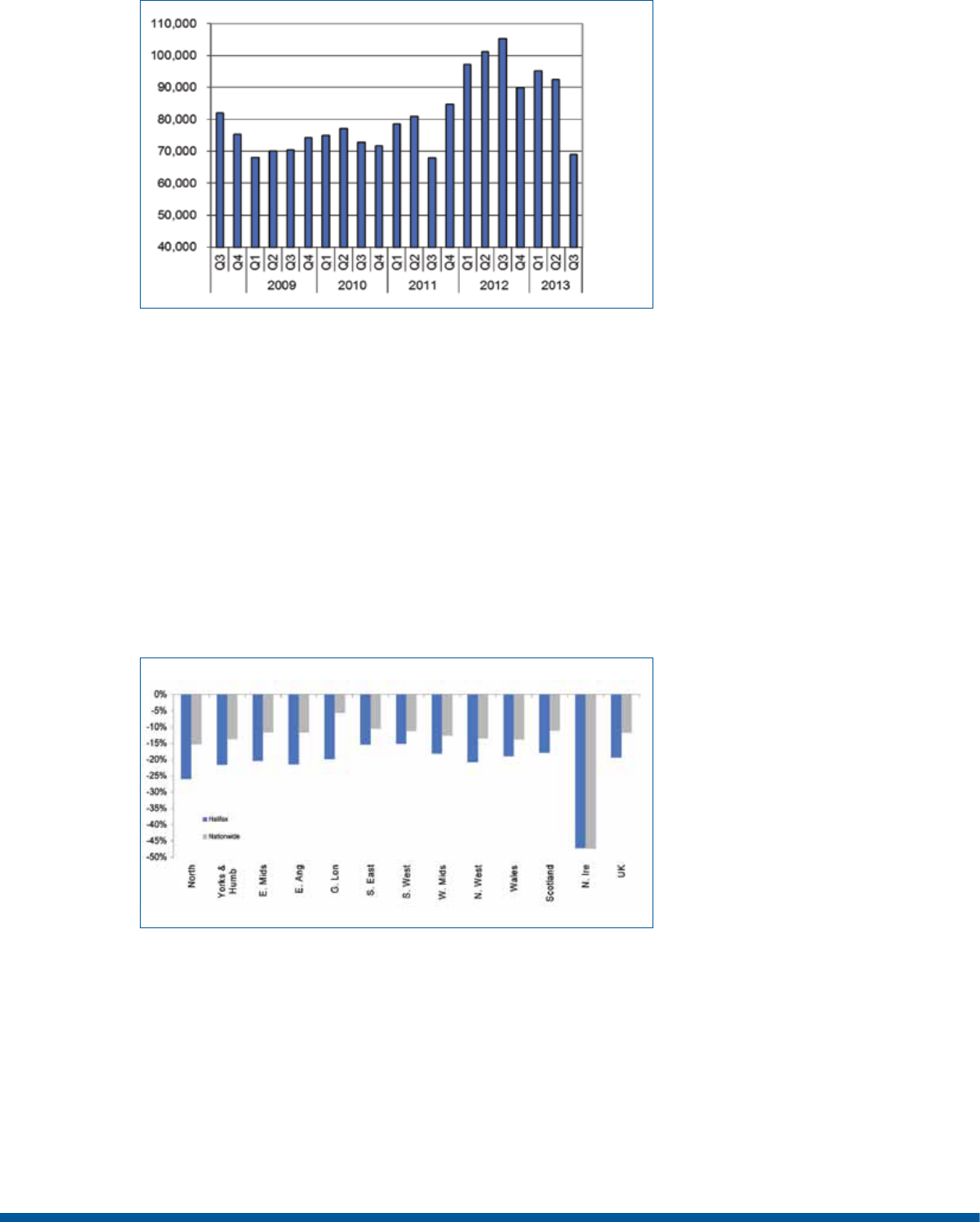

House prices

Landlords are also at risk of house price depreciation. As the prospect of capital gains over the

long-term sits behind many motivations for buy-to-let, short term fluctuations in house prices may

influence the decisions to sell properties and exit the sector. House price falls or negative equity

may not be problematic if the landlord has no intention of selling. However, negative equity may

influence the landlords’ ability to extricate themselves from any adverse impacts of market changes

on their rental investment, as they would incur a shortfall debt to the lender if they sold the property.

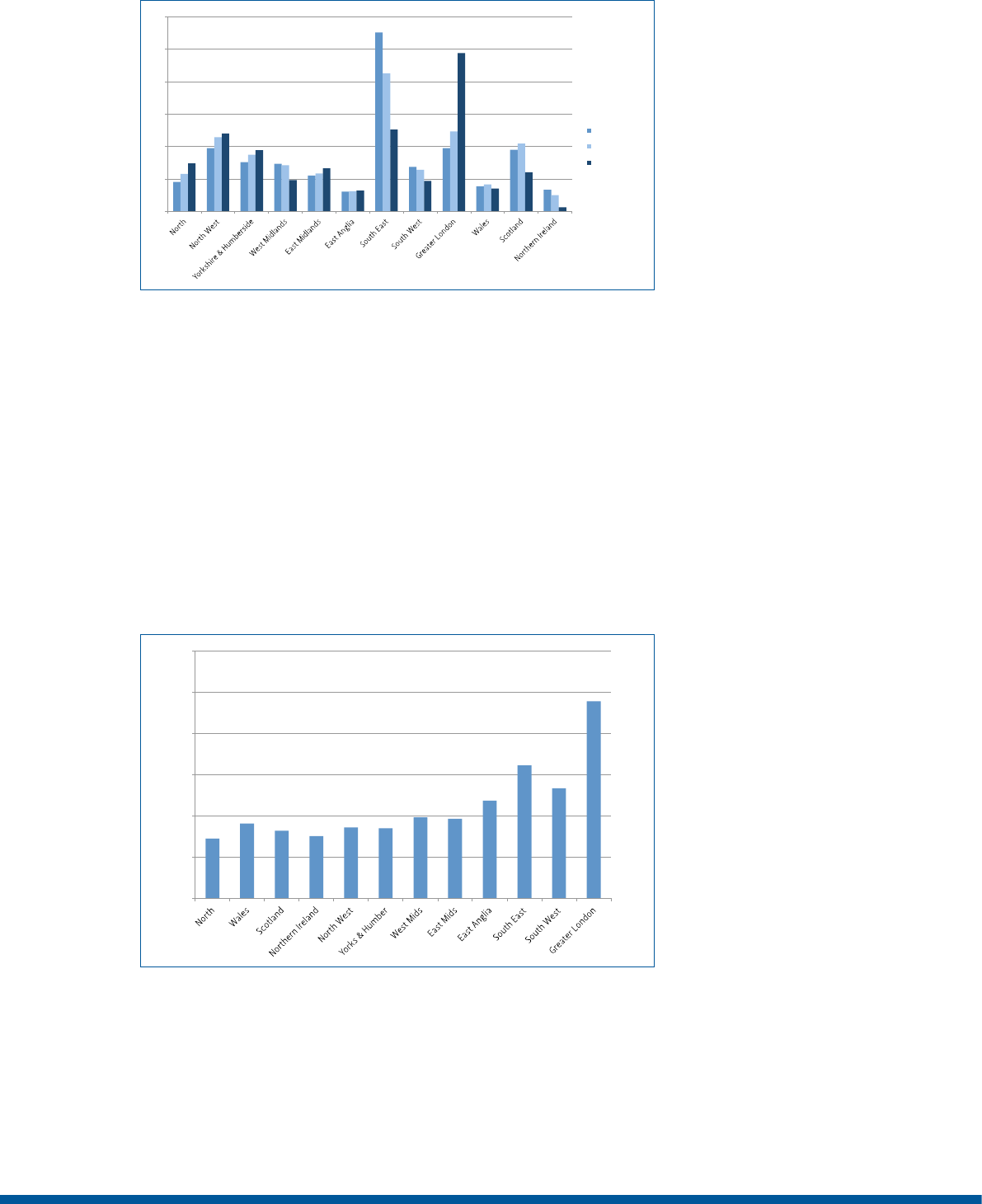

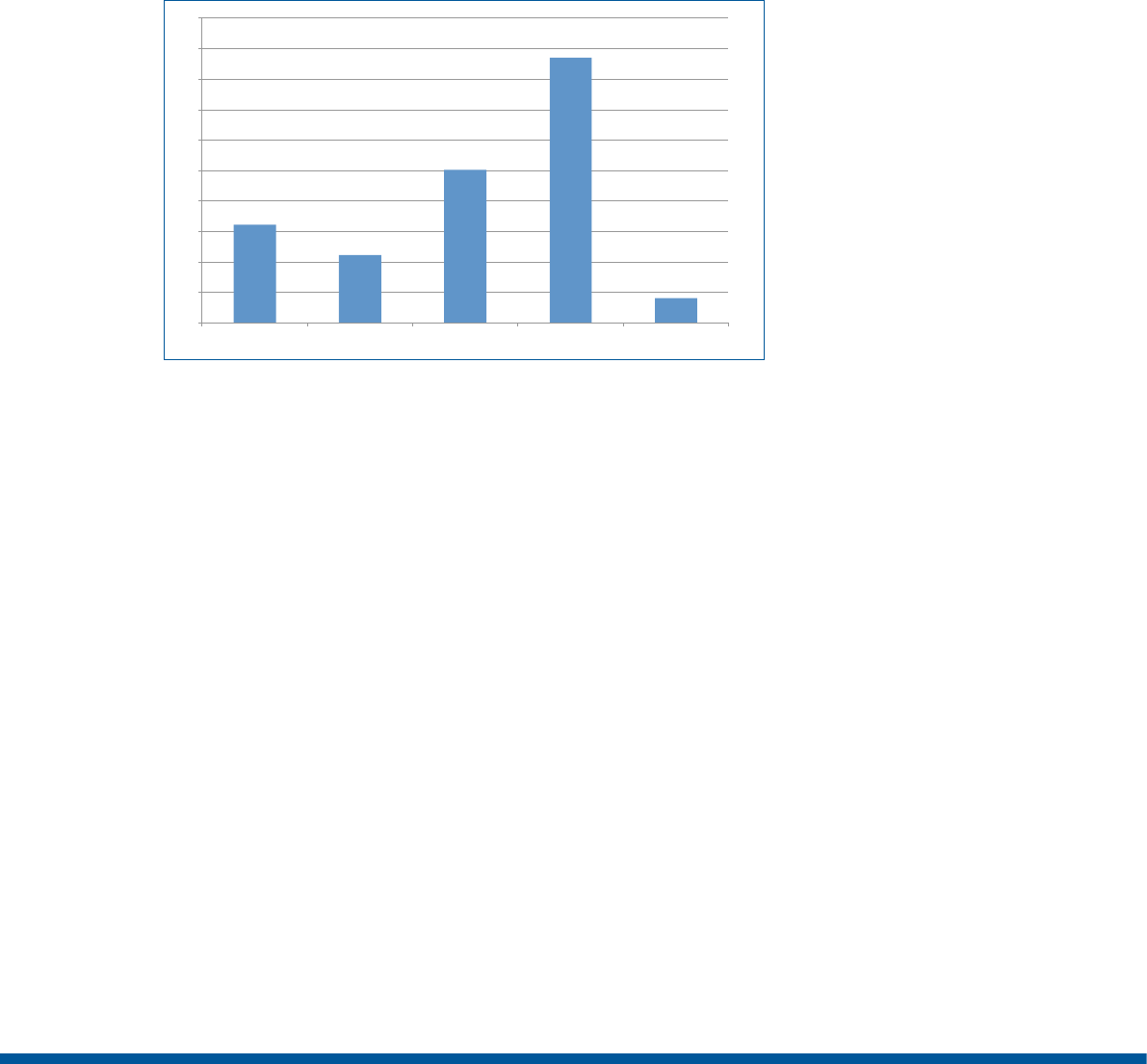

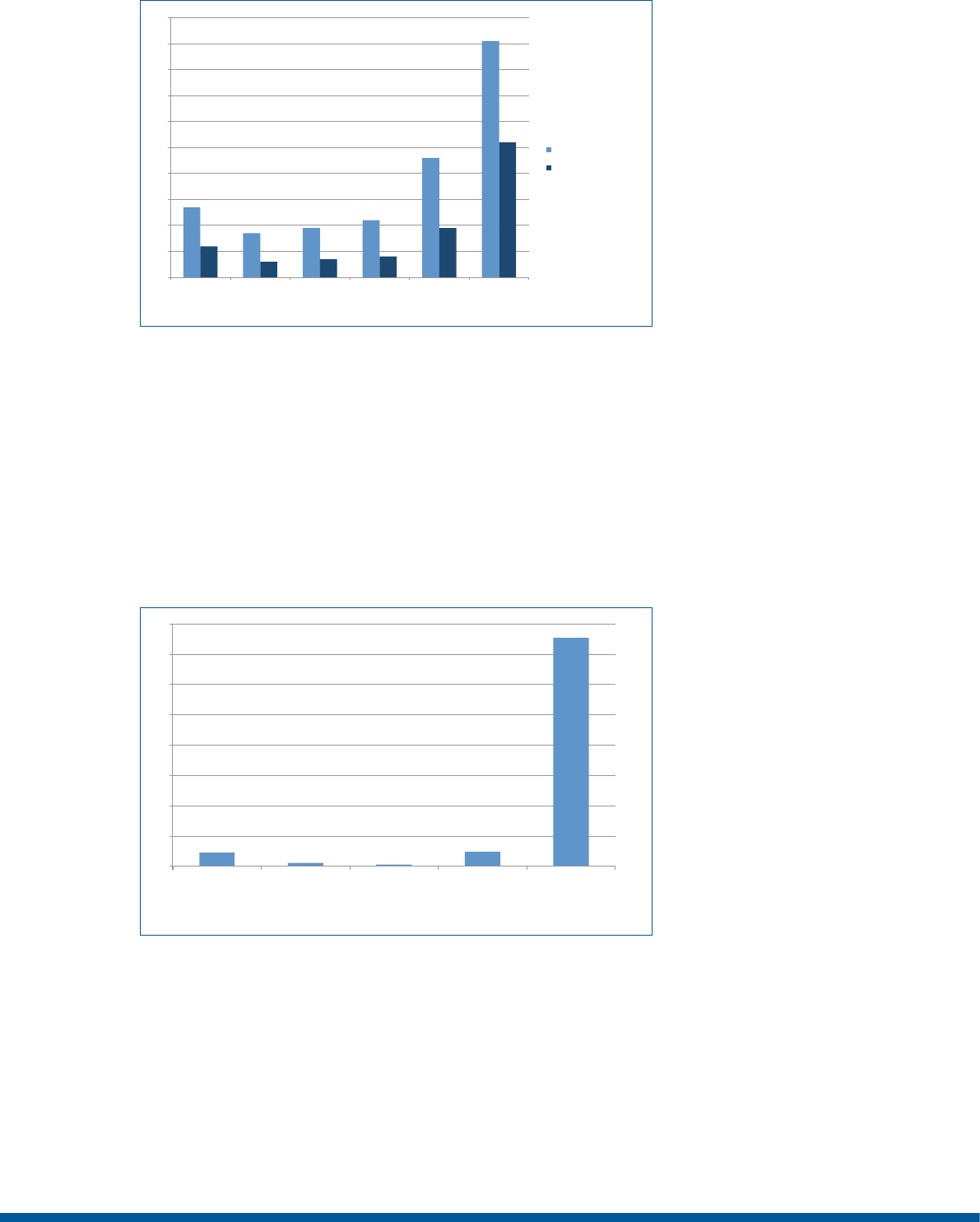

Figure 2.10 depicts the incidence of negative equity across the UK for residential mortgages between

2007 and 2011. It shows that negative equity was by far the most widespread in Northern Ireland,

but also high in the northern regions of England, and in Scotland and Wales. House prices have

increased slightly since 2011 so negative equity may have declined or even diminished in some

locations, however, house price growth is uneven and the regional disparities will remain.

Figure 2.10: Negative equity by region 2007-2011

Source: Purdey (2011)

Anecdotally, some housing sub-markets have been disproportionately affected by negative equity.

Buy-to-let and city centre apartment markets were considered to have been badly affected as

oversupply was widely recognised (French and Leyshon, 2009). As the housing market changed

abruptly from 2008 there were reports of negative equity in these sectors but empirical evidence is

difficult to obtain. Standard and Poor estimated that almost half of buy-to-let property investors would

22

suffer negative equity, compared to only 14-20 per cent of residential borrowers (Property Wire,

2008). Negative equity was also due to valuations inflated beyond what the market could sustain by

the incentives and opaque discounting deals offered by developers to prospective purchasers - often

skewed towards investors - on new-build properties (CML, 2011).

So whether buy-to-let properties are more or less subject to negative equity, the phenomenon’s

relationship to mortgage arrears is uncertain. The CML guards against any association between

negative equity and mortgage arrears in the residential market (Tatch, 2009), but whether landlords

make strategic default decisions when their buy-to-let investment, i.e. not their residential home,

declines in value is unknown.

Mortgage costs

Mortgage costs may also be considered as much a policy risk as a market risk as low base rates

and prudential approach to further lending in the market are arguably as much a result of policy

decisions as a response to market events. In either case, mortgage costs represent an external risk

over which a landlord will have limited control.

The costs of borrowing have changed dramatically over the last decade, and obviously have a bearing

on the sustainability of a buy-to-let mortgage. Neither the Bank of England nor the Financial Conduct

Authority have published typical mortgage rates for buy-to-let loans, but Figure 2.11 illustrates how

mortgage rates in the residential market have changed, showing typical rates for various types of

loans throughout the market cycle. Borrowers on tracker and variable rates were able to reduce their

mortgage payments substantially, limiting the incidence of arrears and possession in comparison to

the market downturn in the 1990s (Ford and Wallace, 2009). In contrast, borrowers on fixed rate

loans were the least able to take advantage of the fall in Bank of England base rates from November

2008, until their loans reverted to the standard variable rate, which following the financial crisis has

moved closer to the rates elsewhere in the market.

The term ‘Mortgage prisoners’ has been coined to describe borrowers unable to remortgage to

secure more advantageous interest rates as they no longer meet the most stringent criteria required

for lending post the financial crisis (FSA, 2012). Not all borrowers unable to remortgage are on the

highest rates, as some may have gone on to standard variable rates, but the FSA estimated that 45

per cent of borrowers in 2012 may have been unable to switch deals.

Again no data is available for buy-to-let loans but landlord borrowers may find remortgaging

difficult as the criteria to obtain loans has changed. The market has reduced the maximum loan-to-

values in particular, with typical LTVs at 75 per cent since 2009, compared to 85 per cent up to 2008

and 80 per cent during 2008 (CML Table MM6). The maximum number of properties a landlord can

hold has also changed, and the maximum loan ceiling any one investor can hold has reduced from

£3 million during 2008-2009 to £1-1.25 million during 2013.

The percentage rental cover required has remained largely the same at 125 per cent throughout the

market downturn, although products with lower rental cover were available during the market peak.

Across the piece, these changes suggest that landlords with mounting payment difficulties will be

unable to switch mortgage deals to reduce outgoings.

23

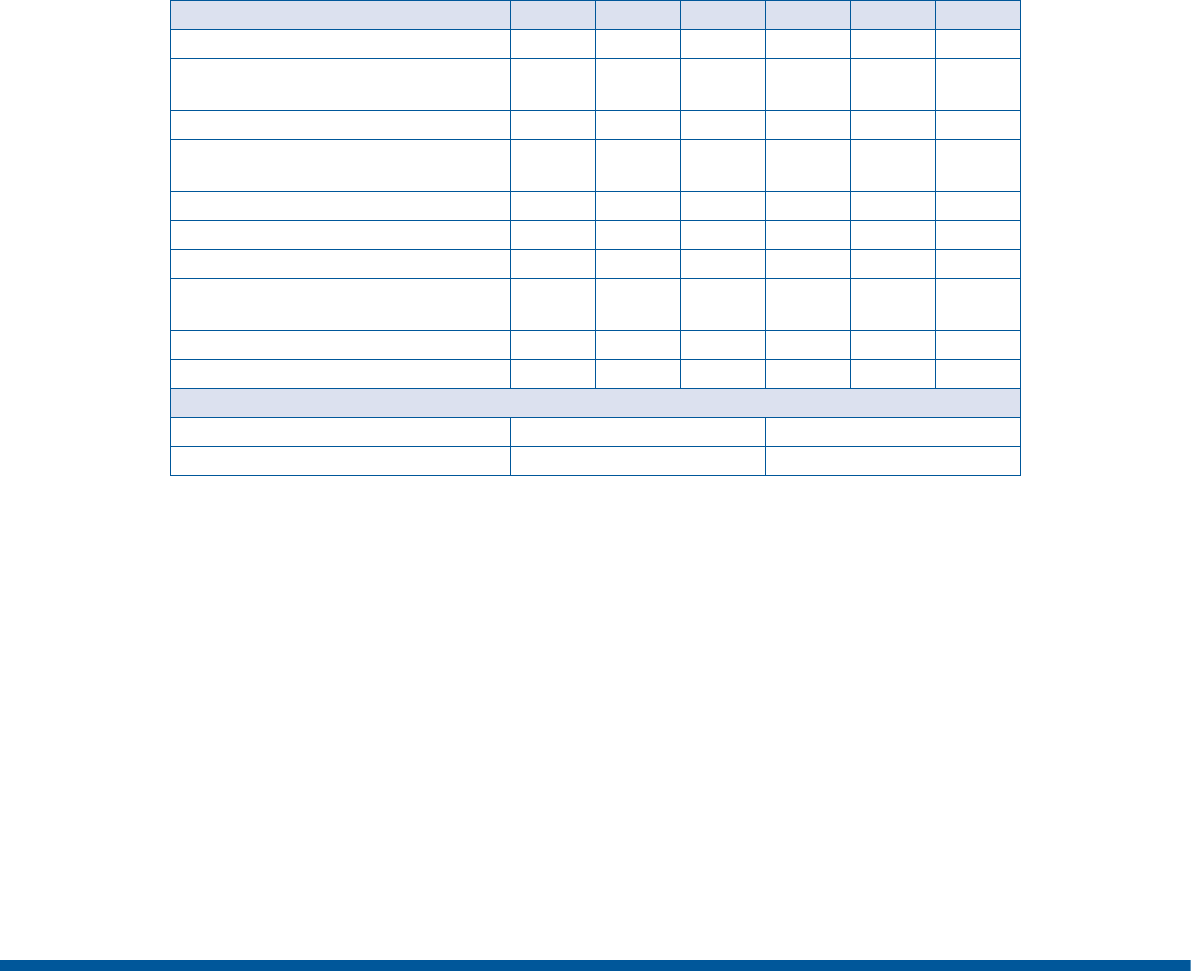

Figure 2.11: Residential regulated mortgage rates by year 2005 to 2012

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

01-Jan-00

01-Jul-00

01-Jan-01

01-Jul-01

01-Jan-02

01-Jul-02

01-Jan-03

01-Jul-03

01-Jan-04

01-Jul-04

01-Jan-05

01-Jul-05

01-Jan-06

01-Jul-06

01-Jan-07

01-Jul-07

01-Jan-08

01-Jul-08

01-Jan-09

01-Jul-09

01-Jan-10

01-Jul-10

01-Jan-11

01-Jul-11

01-Jan-12

01-Jul-12

01-Jan-13

01-Jul-13

01-Jan-14

Lifetime tracker

2 year fix 75% LTV

2 year variable rate 75% LTV

Standard Variable Rate

Source: Financial Services Authority (2012)

Bank of England base rates moved to the historic low of 0.5 per cent in 2009 and since then the

prospect of rising interest rates has been a significant concern. At the time of writing the Governor

of the Bank of England signalled that any UK economic recovery must be sustainable and balanced

prior to any rate rises being implemented, allaying fears of any short-term movement in interest

rates. Although new residential borrowers of regulated mortgages will be subject to stress testing

and affordability checks and should therefore cope better with any rises, existing loans and buy-to-

let loans may not. The BDRC Landlords Survey (BDRC, 2013) reports that 10 per cent of landlords

strongly agreed and 28 per cent agreed with a statement that they were worried about their ability

to pay if mortgage costs were to rise.

Business risks

Landlords have multiple motivations to let property, but several studies indicate that few are

professional full-time landlords. A majority let property as a side-line for medium- to long-term

investment purposes, notably as part of their retirement plan, reflecting the decline in trust and

returns from other assets (Rhodes and Bevan, 2003; Gibb and Naysgaard, 2009, Rugg and Rhodes,

2008; Jones la Salle, 2012).

The management and expertise of some involved in landlord and letting activities has been questioned

(Crook et al., 2009; Rugg and Rhodes, 2008). Most concerns centre on the landlords or agents’

awareness of their obligations or competence, and even sharp practices, in respect of their letting,

rent setting, arranging tenancies and organising repairs. In some instances, informal practices may

favour the tenants (Rugg and Rhodes, 2008), but a less codified approach to the business of being a

landlord that lacks professionalism, may also mean that landlords are not attuned to changes in the

market that could be to their own detriment.

The reliance on rapid capital growth rather than rental income led Leyshon and French (2009) to

note that less than a third of landlords had sustainable business models for their letting activities.

This dependence on capital appreciation meant that there were concerns regarding the impact of

any market downturn on the burgeoning buy-to-let sector and fears that falling capital values in the

housing market could prompt large movements out of the market. However, evidence prior to the

financial crisis showed that landlords were investing for the long term (CML, 2004). Scanlon and

Whitehead (2005) argued that landlords could withstand adverse impacts and that buy-to-let could

have a stabilising effect on the market, but that they would exit if interest rates rose and if the rental

income did not cover the mortgage. Furthermore, Rhodes and Bevan (2003) also found, even at

that time, a small proportion of landlords quite heavily subsidising their rental portfolio or property

24

from their own income, a minority who would be at greater risk in the event of a downturn. While

landlords with fewer properties considered capital growth as a compensation for poor rental income

in these circumstances, professional landlords with property portfolios believed that rental income

should always cover the mortgage and the associated costs of letting, exposing a divergence in

approaches among landlords and a weakness in the small investor sideline landlord model.

Buy-to-let landlords do have greater personal resources than the wider population and Lord et al.

(2013) suggest that they are therefore financially resilient and can cope with substantial income

shocks. Several studies do demonstrate that landlords are indeed typically older, wealthier, well-

educated, higher rate taxpayers, with significant savings and disproportionately living in London

and the South East (Lord, 2013; FSA, 2012; Beatty et al., 2012). Weaknesses in the financial

circumstances of some landlords are, however, evident. BDRC (2013) found 13 per cent of small

landlords, who form the majority of the market, were making a loss at Q3-2013 from their landlord

activities, although this was down from the 16 per cent on Q2-2012. Looking closely at the Lord

et al. (2013) analysis of the Wealth and Assets Survey indicates a minority of financially stressed

landlords, who are, nevertheless, responsible for a significant portion of private rented homes.

For example, 14 per cent of landlords felt the rental income was not sufficient to meet the cost of

everyday outgoings; 11 per cent would have to borrow money and 17 per cent would use a credit

card or overdraft to meet an unexpected major expenditure; and 16 per cent could not cope for

three months if their income dropped by a quarter. Not all landlords struggling financially will

accrue arrears but these data are indicators of financial stress. Although buy-to-let is intrinsically

tied up with personal financial investments, as a business proposition lenders expect it to ‘wash

its face’ or be self-financing. Although, Lord et al. highlighted other conclusions, their study does

indicate that a minority of landlords lack the resources to support adverse events within their buy-

to-let business activities.

Policy risks

In addition to changing wider economic or market factors, policy and regulatory changes may also

exert pressure on landlords’ finances. The most high profile change over the last decade have been

the changes to housing benefit, which affects the tenants’ ability to meet their rent commitments.

Housing benefit for private tenants was reformed from 2008 onwards and a local housing allowance

paid. No longer tied to the rent charged, allowances were based on flat rates applicable to different

size properties and the drive was to increase tenants’ personal financial responsibility by making

payments to the tenant for them to pass onto their landlord. Prior to this it had become common

practice for landlords and tenants to agree that housing benefit could be paid directly to the landlords.

Further changes to housing benefit were made from 2011 onwards:

• Payments routinely paid to tenants not landlords directly (April 2008)

• Maximum local housing allowance reduced from 50 percentile local rents to 30 percentile (April

2011)

• The single room rate previously applicable to people aged under 25 was extended to people

aged under 35, meaning people between the ages of 25 and 34 would no longer receive benefit

to cover a one bedroom accommodation, only for a room in a shared house (January 2012)

• Caps on the maximum amounts of local housing allowances in each area, and a removal of a

five bedroom rate (April 2013)

• A cap on the total amount of benefits an applicant can receive at £500 per week for parents

and £350 per week for single people, which affects larger families and/or families in high rental

areas (April-October 2013)

• The use of sanctions designed to induce changes in claimant behaviour – temporary disqualifications

from benefits or amounts deducted from entitlements for certain periods – has also expanded

25

An interim analysis of the impact of recent changes to the local housing allowance found that

landlords who let in areas dominated by the local housing allowance market were experiencing

pressures on their loan repayments due to a combination of an inability to attract alternative tenants,

declining rents, limited ability to increase rents and high mortgage costs and they feared a rise in

interest rates (Beatty et al., 2012; 2013). However, landlords did note that they could not wholly

attribute adverse impacts and increased arrears in the housing benefit market to the changes in the

local housing allowance as tenants were also subject to the much broader ‘squeeze’ on households’

finances apparent during this downturn. The analysis also highlighted the spatial impacts of the

policy changes, with the greatest reductions in tenants’ entitlements being in the London and other

high cost areas, such as Cambridge and York. In some lower cost areas, the tenants had been able

to get the landlords to absorb these reductions in housing benefits, but in higher cost areas there was

some evidence of landlords reducing their lets to tenants in receipt of housing benefit as alternative

tenants were available. The BDRC Landlords Survey (2013) does indicate a substantial reduction in

the proportion of landlords willing to let to tenants in receipt of local housing allowance from 46 per

cent in 2010 to 22 per cent in 2013.

Beatty et al. (2013) also report that some landlords were nervous about the introduction of Universal

Credit, the new benefit that will see the majority of social security benefits rolled into a single

payment. Landlords viewed it as the end of a discrete housing allowance and perceived risks to their

rental stream. A survey of landlords by the National Landlords Association (2013b) found that 70

per cent of landlords with tenants in receipt of housing benefit are concerned about the changes.

Currently, landlords must wait 8 weeks of non-payment of rent before requesting payments be

switched from the tenant to the landlord. Under Universal Credit, a review process will start earlier

regarding the tenants’ ability to manage their payments, after just four weeks rent arrears, and

payments of the housing element of Universal Credit will revert to the landlords after 8 weeks, so

landlords’ perceptions of additional risks may be unwarranted. Provision to pay the housing element

to landlords directly from the outset for households deemed vulnerable in terms of the guidance and

regulations and those unable to manage money will remain. The roll-out of Universal Credit is not

anticipated to be complete until 2017, so the full impact of the changes will be unknown for some

time.

Since 2006 landlords of Houses in Multiple Occupation have been required to be licensed by law

(BRE, 2010). Criteria for entry and operation under these local schemes vary, but often involve a

cost to the landlord for a permit and possibly the costs of upgrading the property to meet certain

standards. The increasing importance of the private rented sector to the housing market has

prompted further calls to reform the sector, to improve the quality of management, maintenance and

offer stable renting (Rugg and Rhodes, 2008; Shelter, 2011). Several local authorities and devolved

regions are now operating accreditation and local licensing schemes for all landlords, regardless of

the type of properties let. The impact of local licensing arrangements and any associated costs on

landlords’ finances is uncertain.

As mentioned, policy and practice in respect of offering tenants longer tenancies is evolving. Two

recent reports consider the potential impact of longer tenancies on landlords’ business models,

addressing assumptions that greater tenant security would jeopardise landlords’ business plans.

Lloyd (2013) argues that as landlords are on the whole evidently wealthier than the wider population

they can sustain a strengthening of tenants’ rights, through innovations such as longer tenancies,

even if it reduces profitability and that if such rights were enacted that landlords would not exit the

sector in significant numbers. Lloyd’s report was based on Lord et al.’s (2013) analysis of landlords’

personal financial circumstances not their business finances, but Jones La Salle (2013) used data

from eight case study landlords to model the impact of longer tenancies on landlords’ business plans

and found that their returns would be enhanced by longer stable tenancies.

26

Conclusions

The stock of buy-to-let mortgage arrears has fallen at a sharper rate than arrears in the residential

mortgage market, but the proportion of loans subject to possession in the buy-to-let market has been

in excess of the residential market. The extent to which personal rather than business or market factors

emerge as significant triggers for mortgage arrears in the residential market – unemployment, ill

health or relationship breakdown- are also factors in landlords’ accounts of their mortgage arrears is

unknown. Buy-to-let is, however, formulated by lenders and regulators as a self-supporting business

enterprise so in theory should not be affected by these events. Little is known about the determinants

of buy-to-let landlord arrears but we can speculate about some of the pressures landlords may face.

There has been some volatility in the rent levels, vacant periods, and house price values throughout

the market downturn and significant regional differences are evident that may affect landlords’

ability to sustain their mortgage payments. The landlords’ experiences seem to be improving but

the evidence suggests a small pool of financially precarious landlords. The next chapter examines

evidence from the English Housing Survey, which reflects a cross-section of the market experiences

during 2009-2010. The analysis provides an overview of landlords’ circumstances and the factors

associated with problematic mortgage costs.

27

3: Evidence from the English Housing Survey Private

Sector Landlords Survey 2010

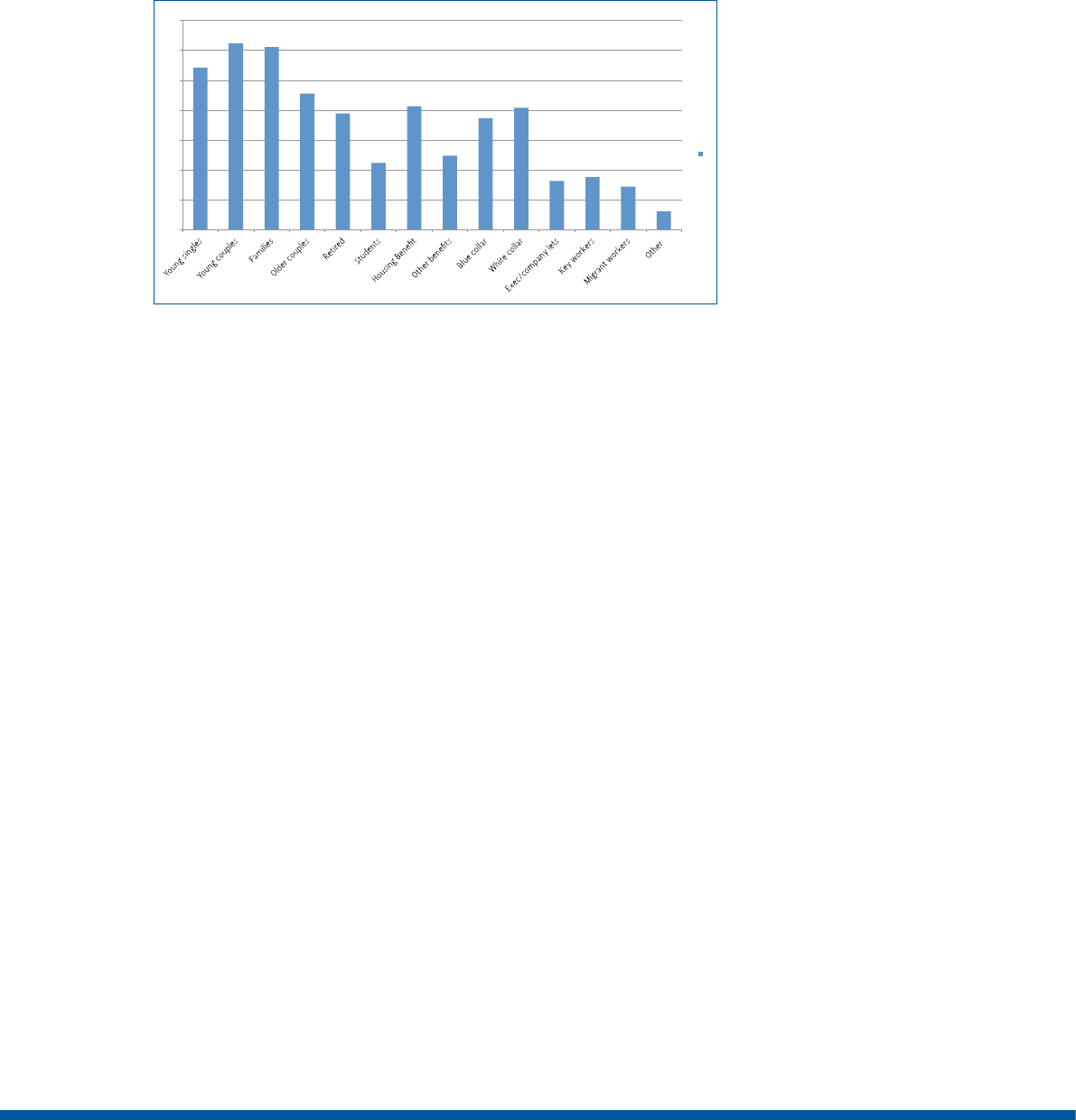

Summary

• Over a fifth of landlords in the 2010 English Housing Survey Private Landlords Survey

reported problems with their mortgage costs. A total of 16 per cent reported small problems

with mortgage costs and six per cent reported serious problems.

• Letting in areas with selective licensing schemes was significantly associated with landlords

reporting mortgage cost problems but fell away as an explanation for problems after further

analysis. This suggests that licensing reflects by proxy the types of neighbourhoods, lettings

and experiences subject to these schemes.

• Tenants being in receipt of housing benefit were associated with tenant rent arrears but, at

the time of this survey, there was no association with landlords losing money as a result.

Moreover, the mechanism by which housing benefit may have contributed to tenant arrears

at this time was unclear, as there was no association between rent arrears and shortfalls in

housing benefit payments, or with tenants receiving the benefit directly.

• As housing benefit administration problems were significantly associated with landlords

reporting mortgage cost problems it could be that administrative delays, payment in

arrears and/or problems with reclaiming overpayments from landlords were the core issues

concerning landlords during 2009-2010 when the data was collected.

• The most significant factors that increased the odds of a landlord reporting problems with

their mortgage costs were letting property in the North East, and reporting problems with

finding builders, tenant damage, local housing benefit administration, deposit disputes

and asking tenants to provide a reference. These factors reflect market conditions in some

locations, policy issues in respect of housing benefit administration and business risks in

respect of managing tenancies.

• These factors account for a quarter of the variance of landlords reporting problems with their

mortgage costs, suggesting that other factors unobserved in the data are also important.

Introduction

This chapter presents the findings of the analysis of the English Housing Survey Private Landlords

Survey (EHS-PLS 2010). As mentioned in the first chapter, these data were collected during 2009-

2010 since when the economic, housing and mortgage market indicators have changed. In addition,

social security policy in respect of housing benefit has been further amended, which has the capacity

to disrupt landlords’ finances if housing benefit no longer covers the rent, for example. The EHS-PLS

data nevertheless represent a robust portrait of landlords’ circumstances, experiences and attitudes

towards their letting activities and mortgage costs.

The next section provides an overview of landlords and their letting activities across the whole

market, and then continues by examining the attributes of landlords and tenants who are identified

as having an outstanding mortgage or loan and are associated with problematic mortgage costs.

The final section presents the findings of the statistical analysis that identifies those factors that

increase the odds of landlords reporting problematic mortgage costs. The analysis shows a wide

range of factors that, taken as a whole, could suggest that landlords reporting problems with their

mortgage costs is associated with letting to individuals or locations in some disadvantage.

28

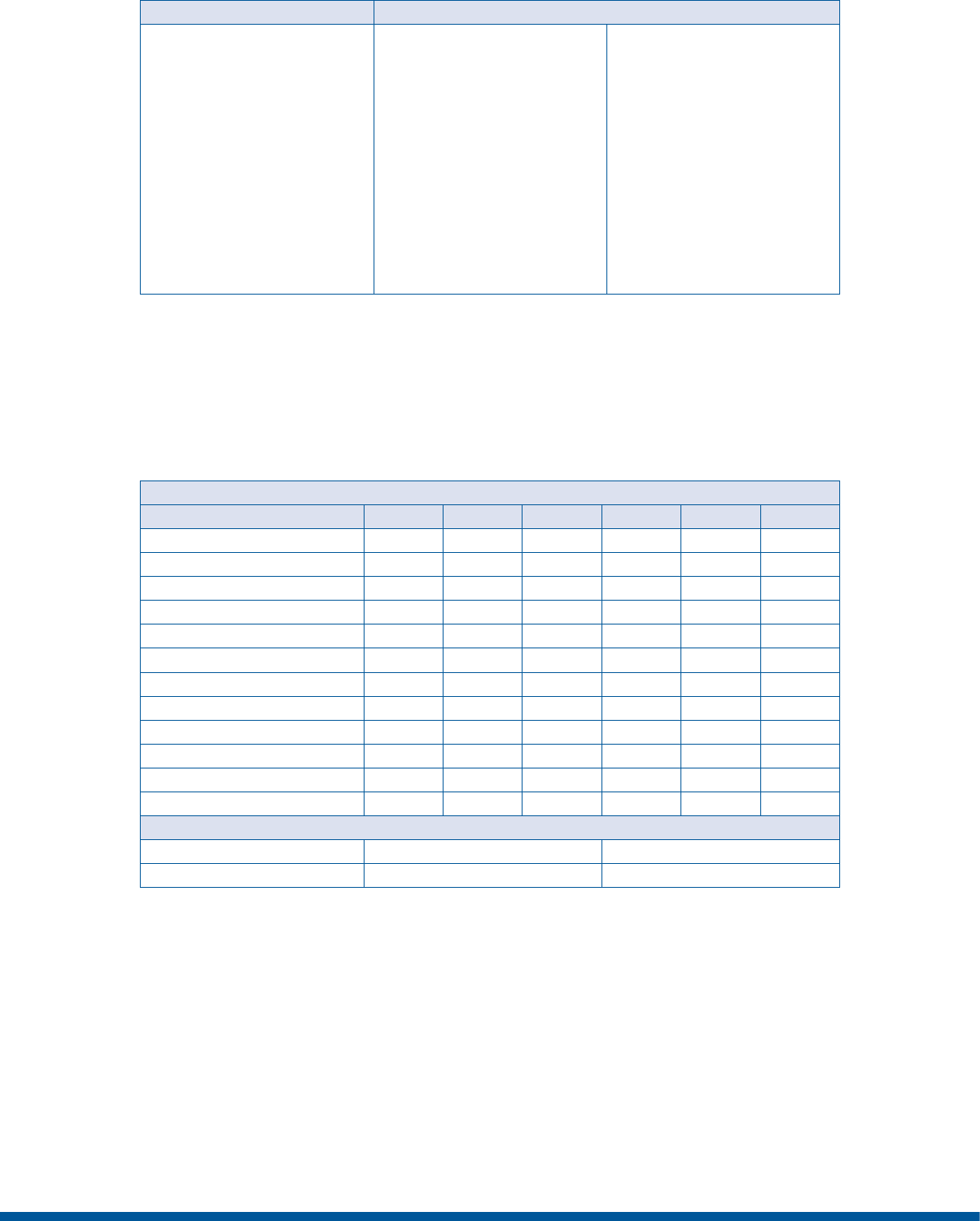

Profile of landlords

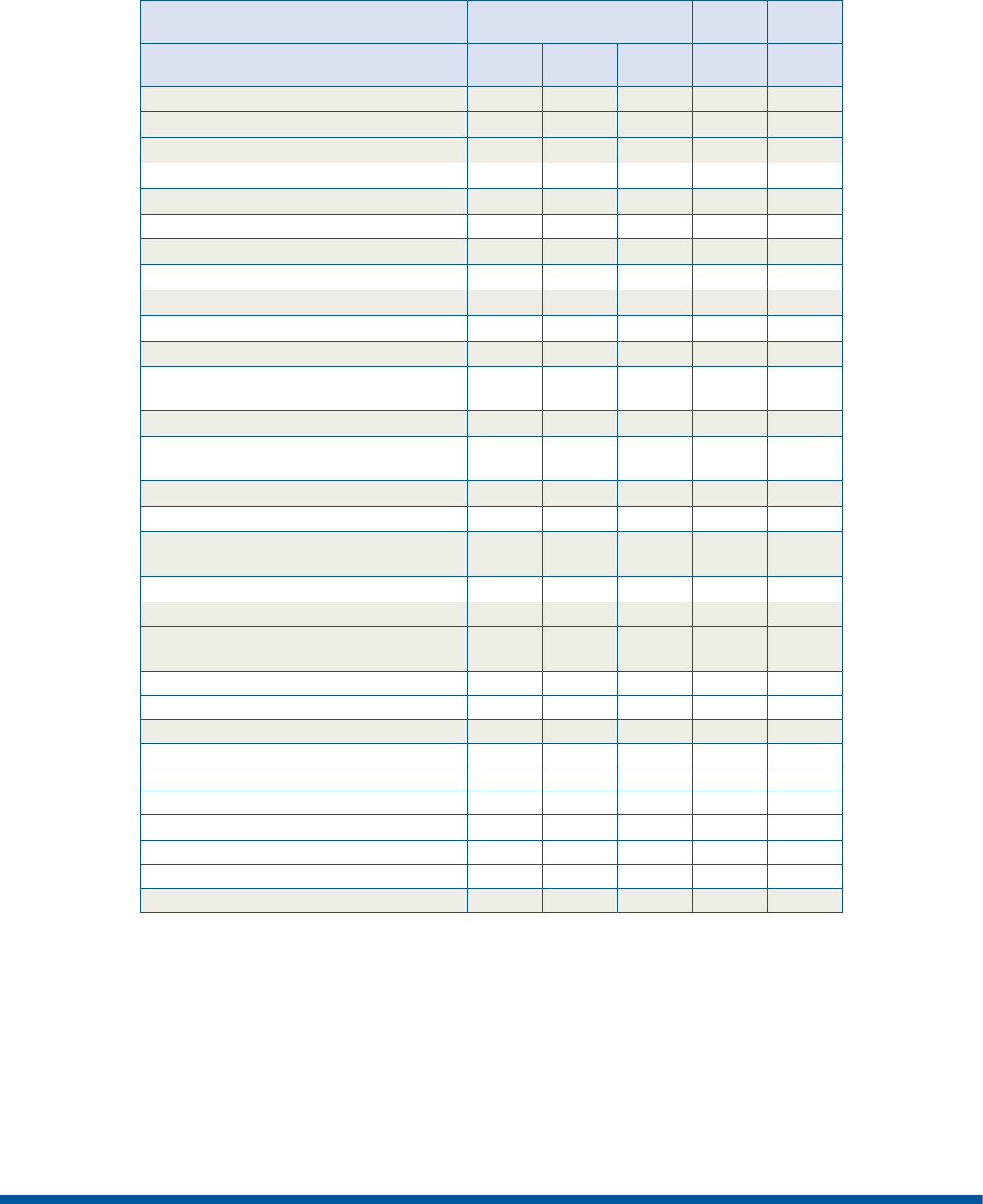

Landlord characteristics

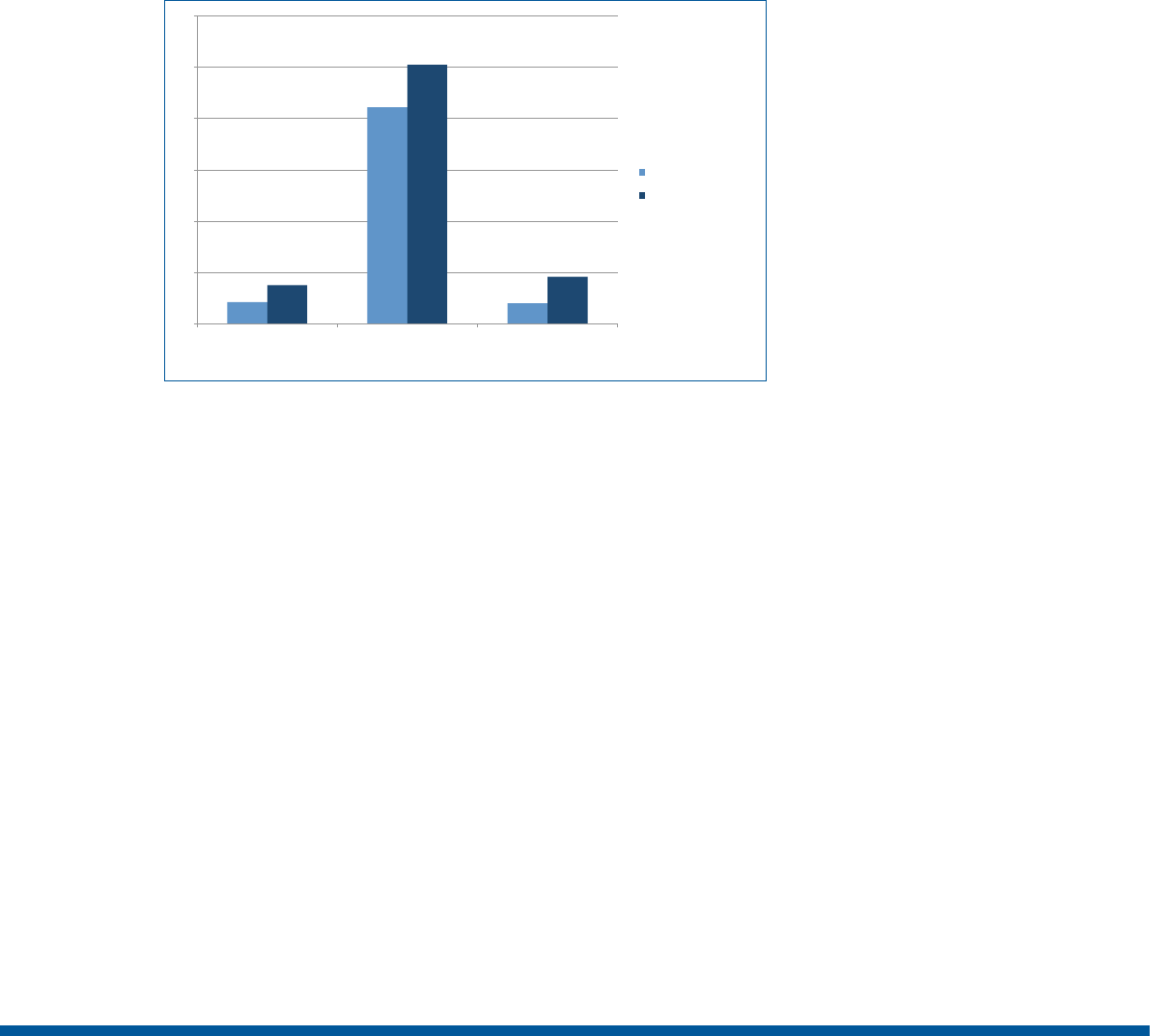

A total of 73 per cent of landlords are individuals, couples or groups of individuals, compared to 27

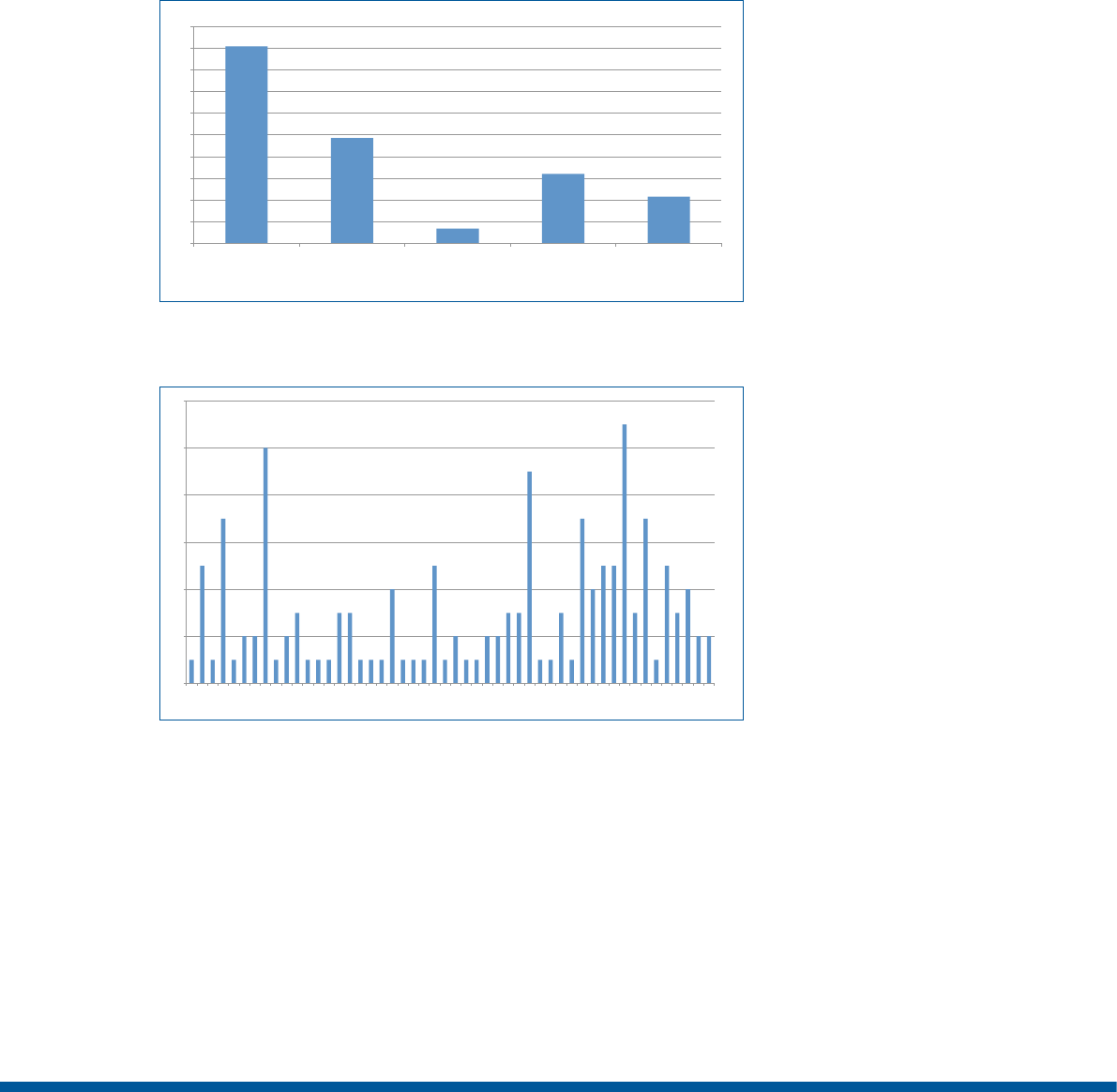

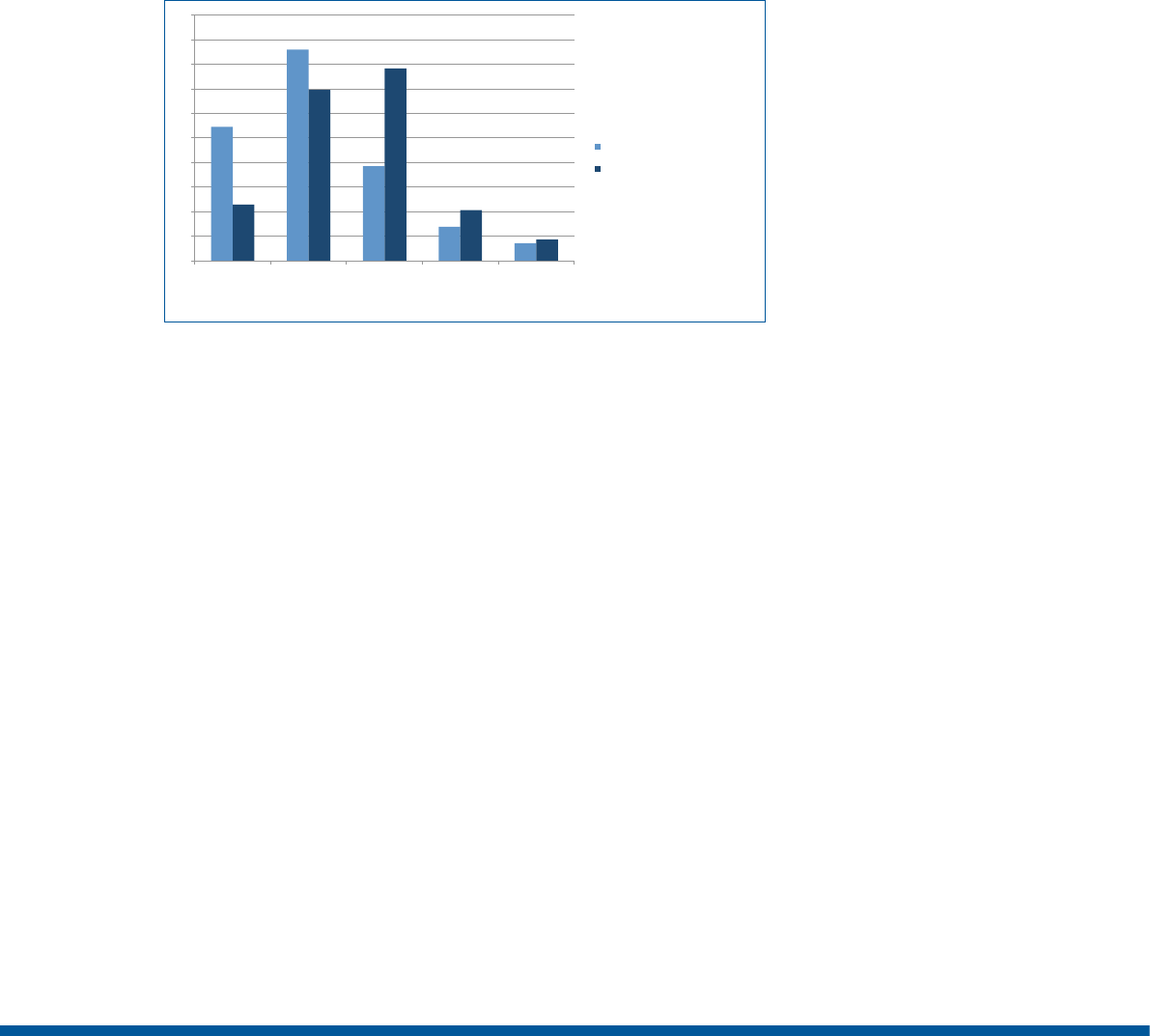

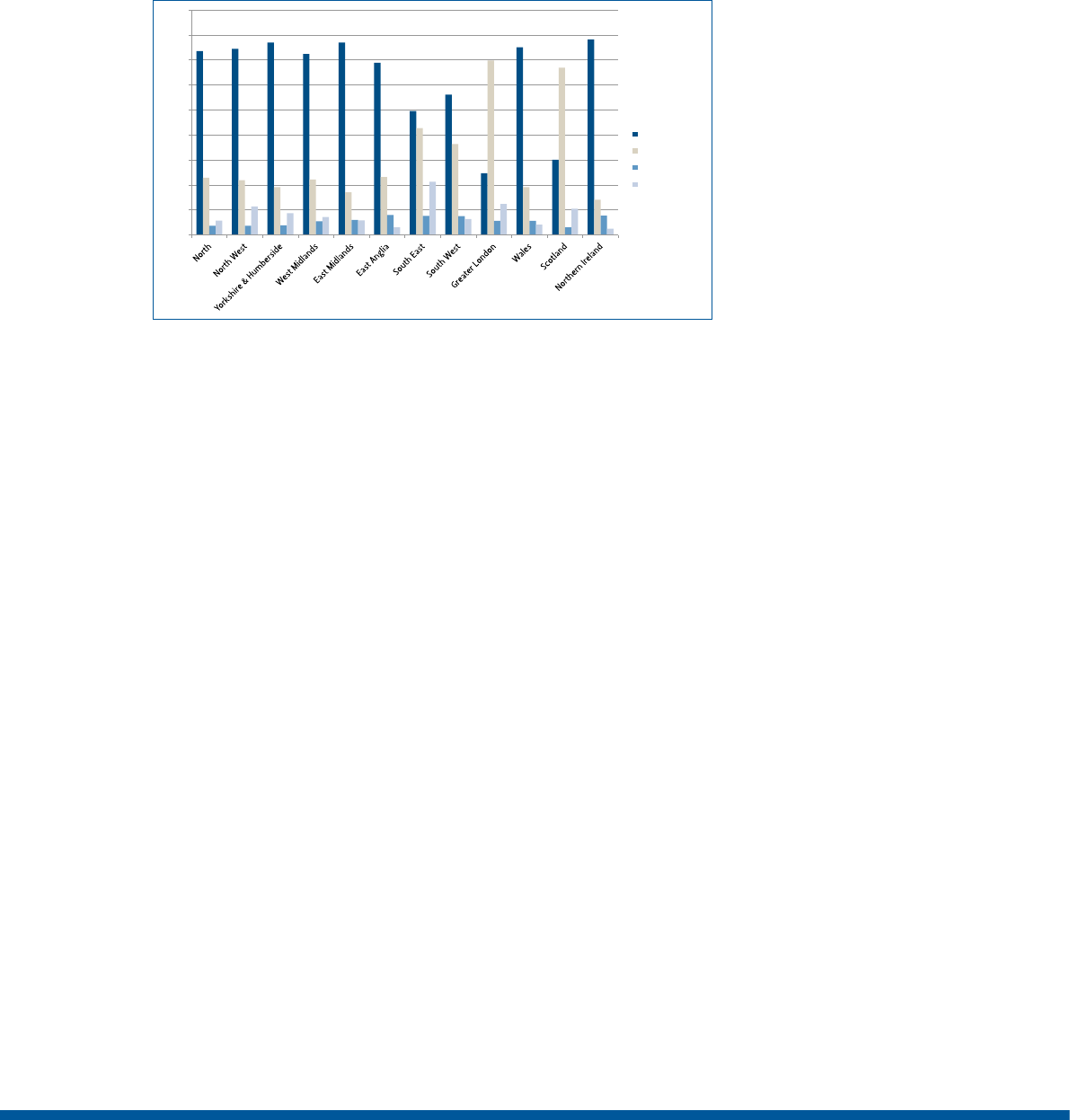

per cent that are a company or other organisation (Figure 3.1).

Companies have been in the letting market consistently over time, but there has been substantial

change in the entry of individual landlords to the market, with some notable spikes after the Housing

Act 1988, that introduced shorthold assured tenancies and rent deregulation; following the advent

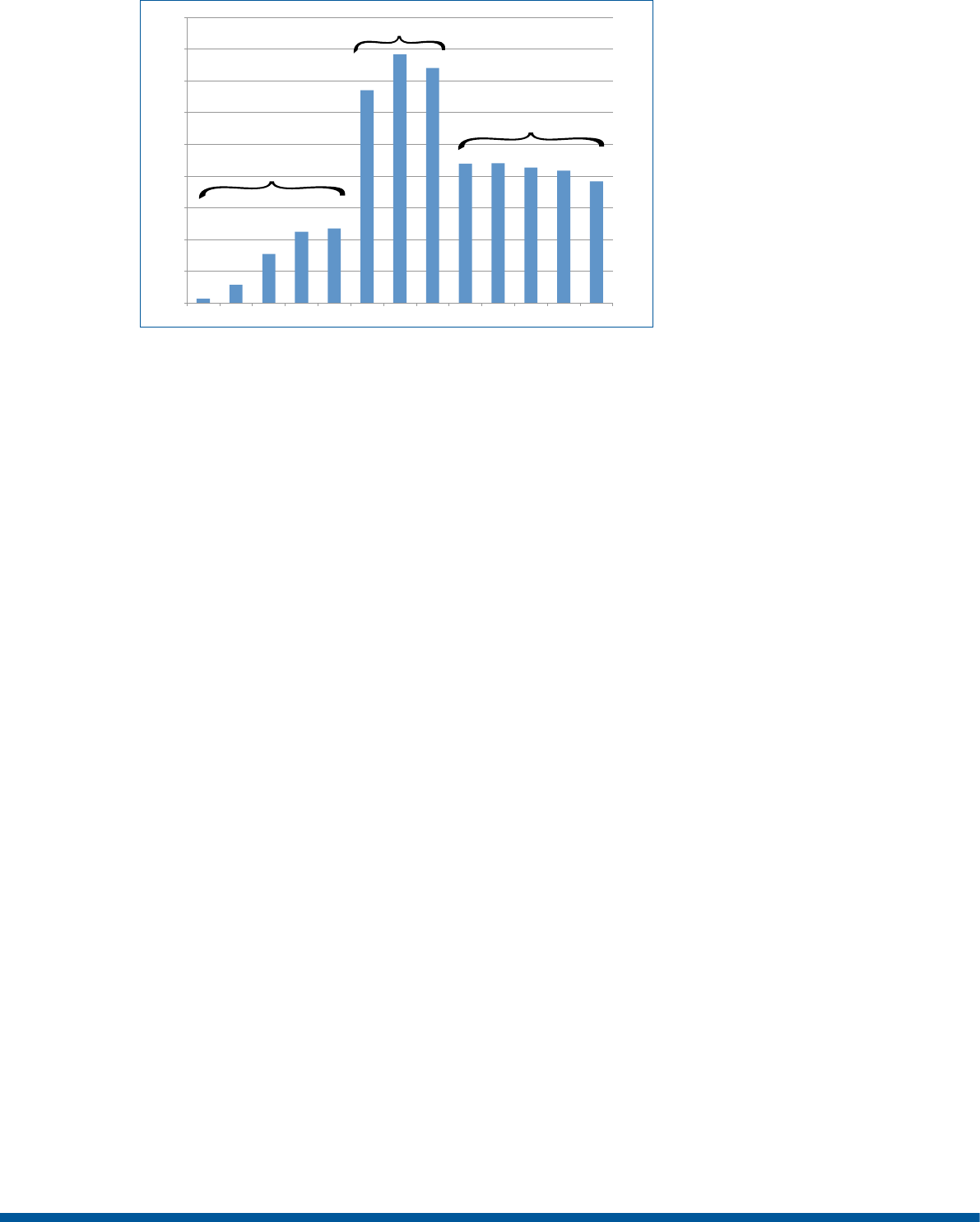

of buy-to-let mortgages in 1996; and during the rising property markets of the 2000s (Figure 3.2

and Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.1: Type of landlord (%) (n=1050)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

An individual A couple A group of individuals A company Some other

organisation

Source: EHS-PLS 2010

Figure 3.2: Year companies started

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

1946

1947

1948

1950

1952

1955

1956

1960

1962

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

1975

1976

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

Source: EHS-PLS 2010 (n=209)

NB 1945 or before

29

Figure 3.3: Year individuals started letting letting

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Source: EHS-PLS 2010 (n=638)

Eleven per cent of landlords work in property or estate management and 26 per cent in the building

or maintenance trade. A fifth (21 per cent) hold a qualification in finance, property, building or the

law. A fifth of individual landlords (19 per cent) also say letting is their main business, compared

to almost half of companies (48 per cent). Half of all landlords are members of a professional

organisation, compared to 59 per cent of company landlords and 46 per cent of individuals.

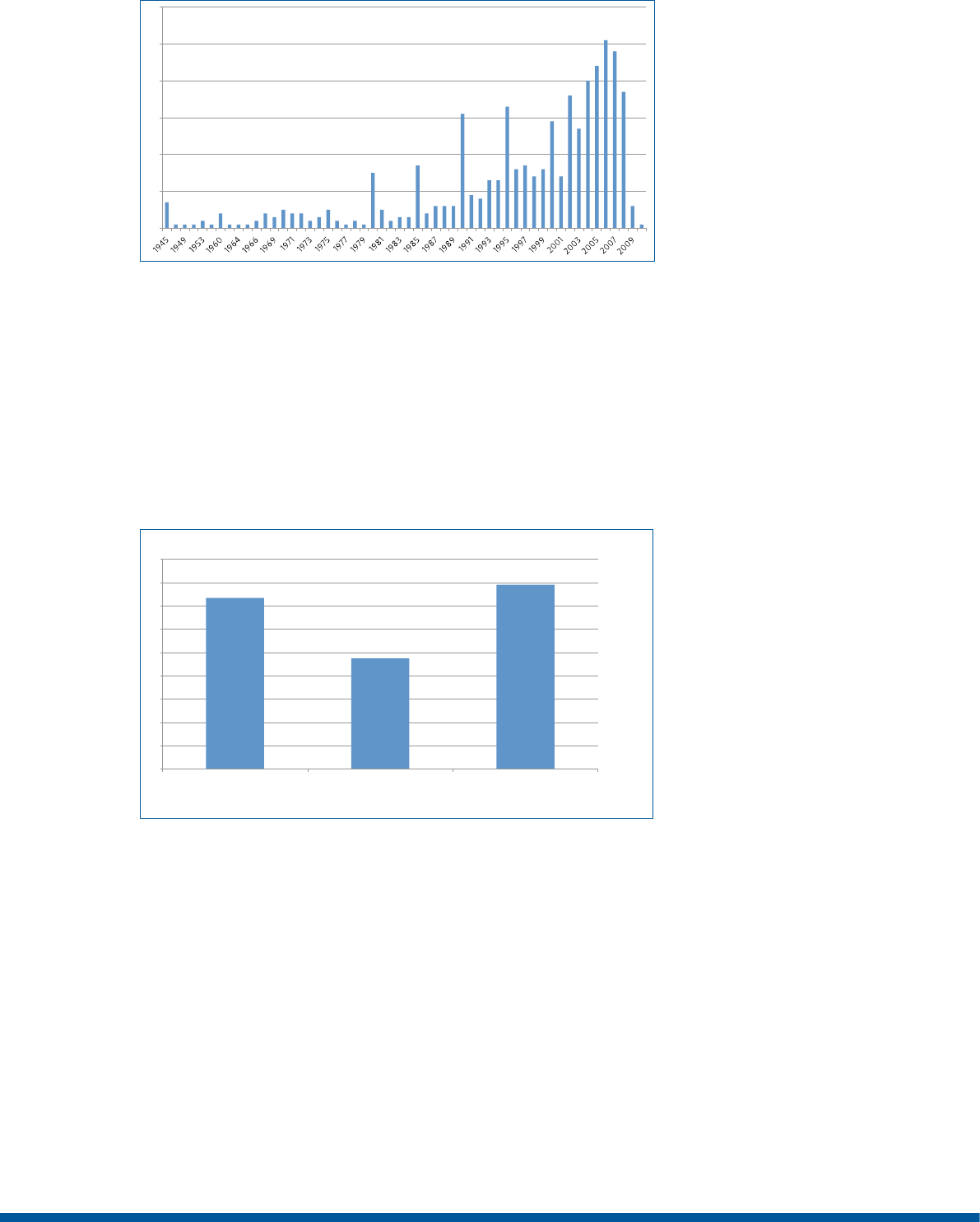

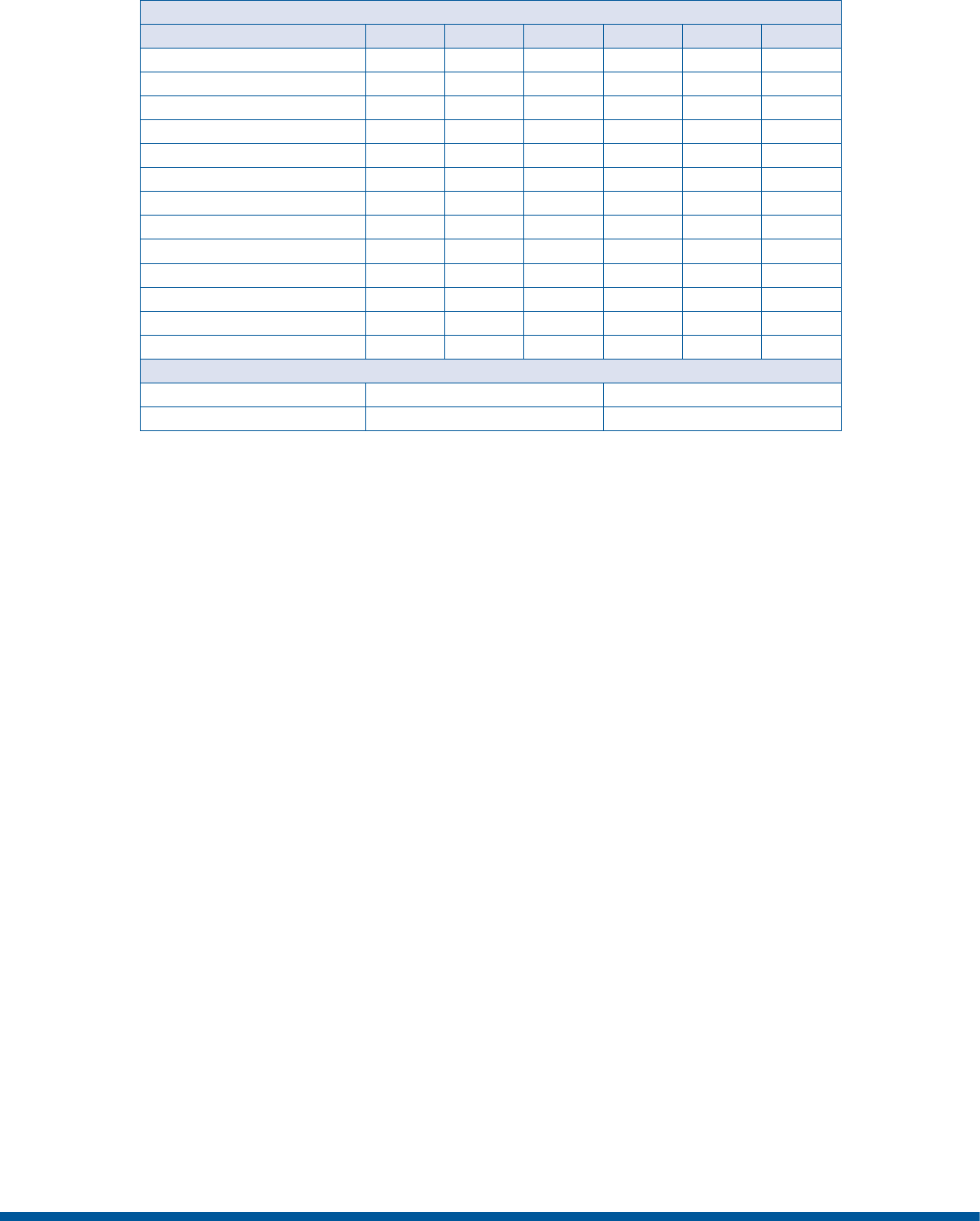

Two-fifths of landlords consider both rental income and rising property values as important to their

investment strategy (Figure 3.4). Rental income is the sole priority for only 35 per cent of landlords,

and capital values the sole motivation for nearly a quarter of investors.

Figure 3.4: Landlords’ investment priority (n=659)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Rental income Rising property values Both

Source: EHS_PLS 2010

Around two-thirds of all landlords regard their property as a pension investment, but a third of all

landlords hold property for other purposes. Individuals overwhelmingly regard their letting activities

as an investment for pension purposes (77 per cent), and although this is important to companies too

(40 per cent), companies also let property to house employees and for other reasons (Figure 3.5).

30

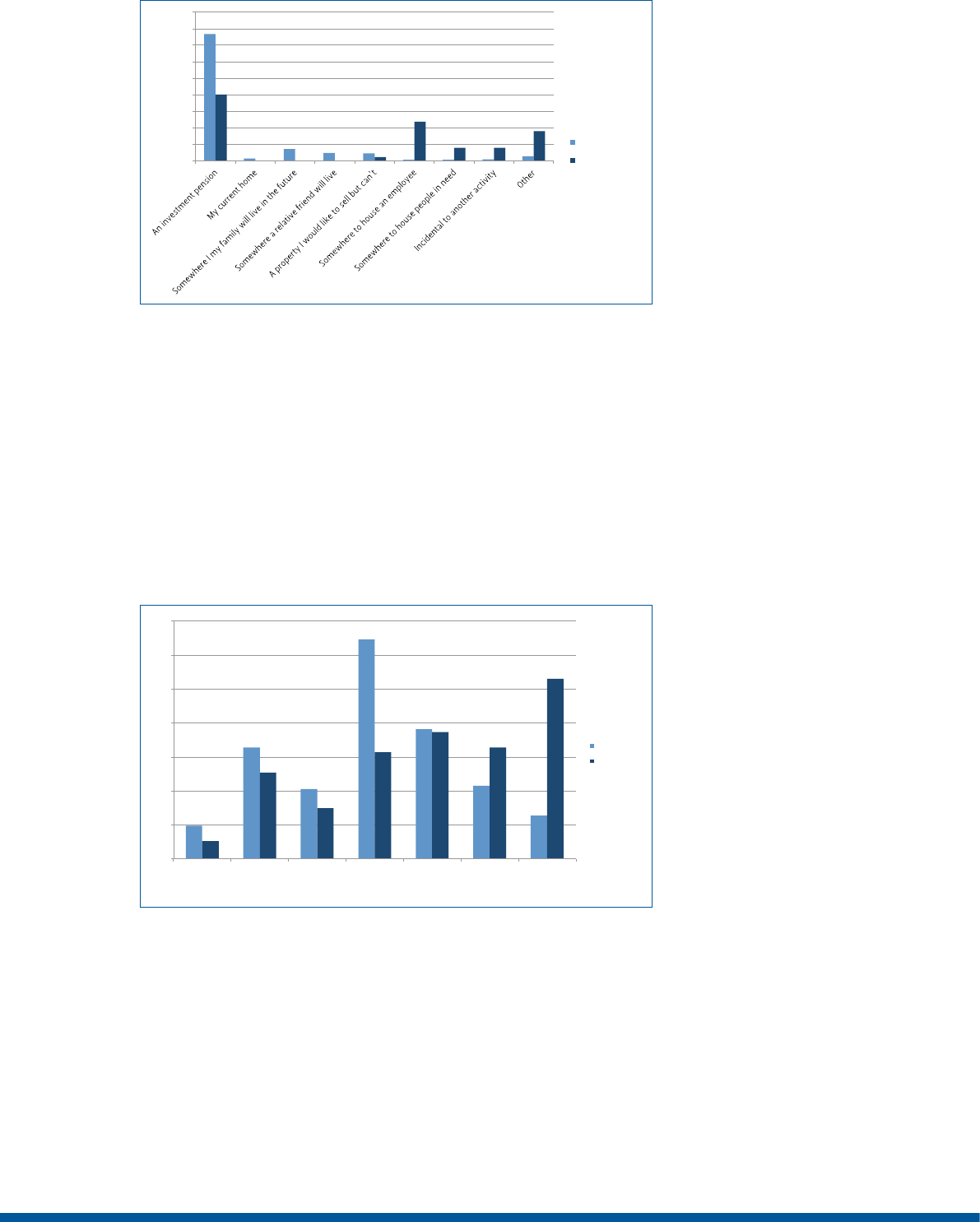

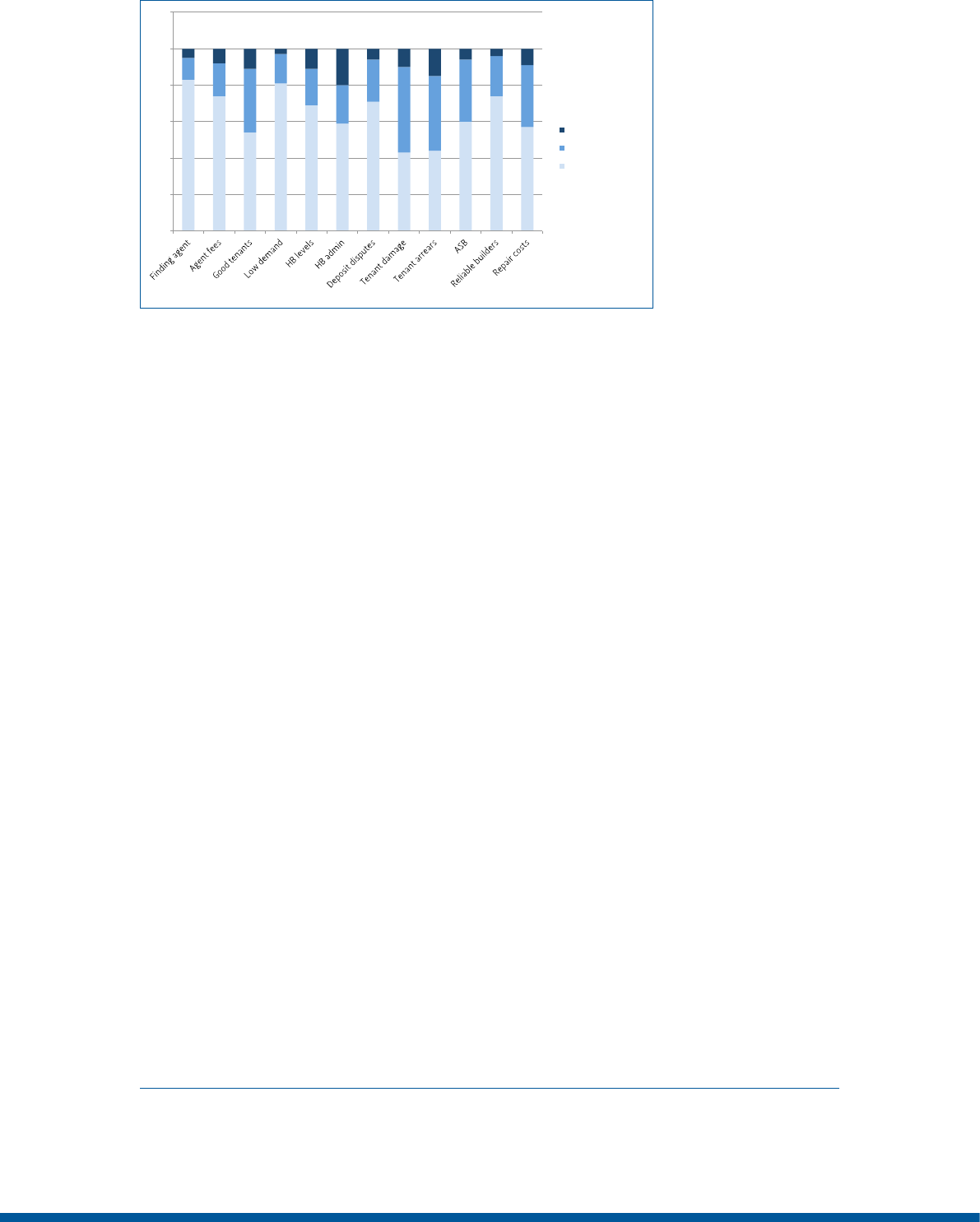

Figure 3.5: How landlords regard their property (n=754)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Individuals

Companies

Source: EHS-PLS 2010

Property and location

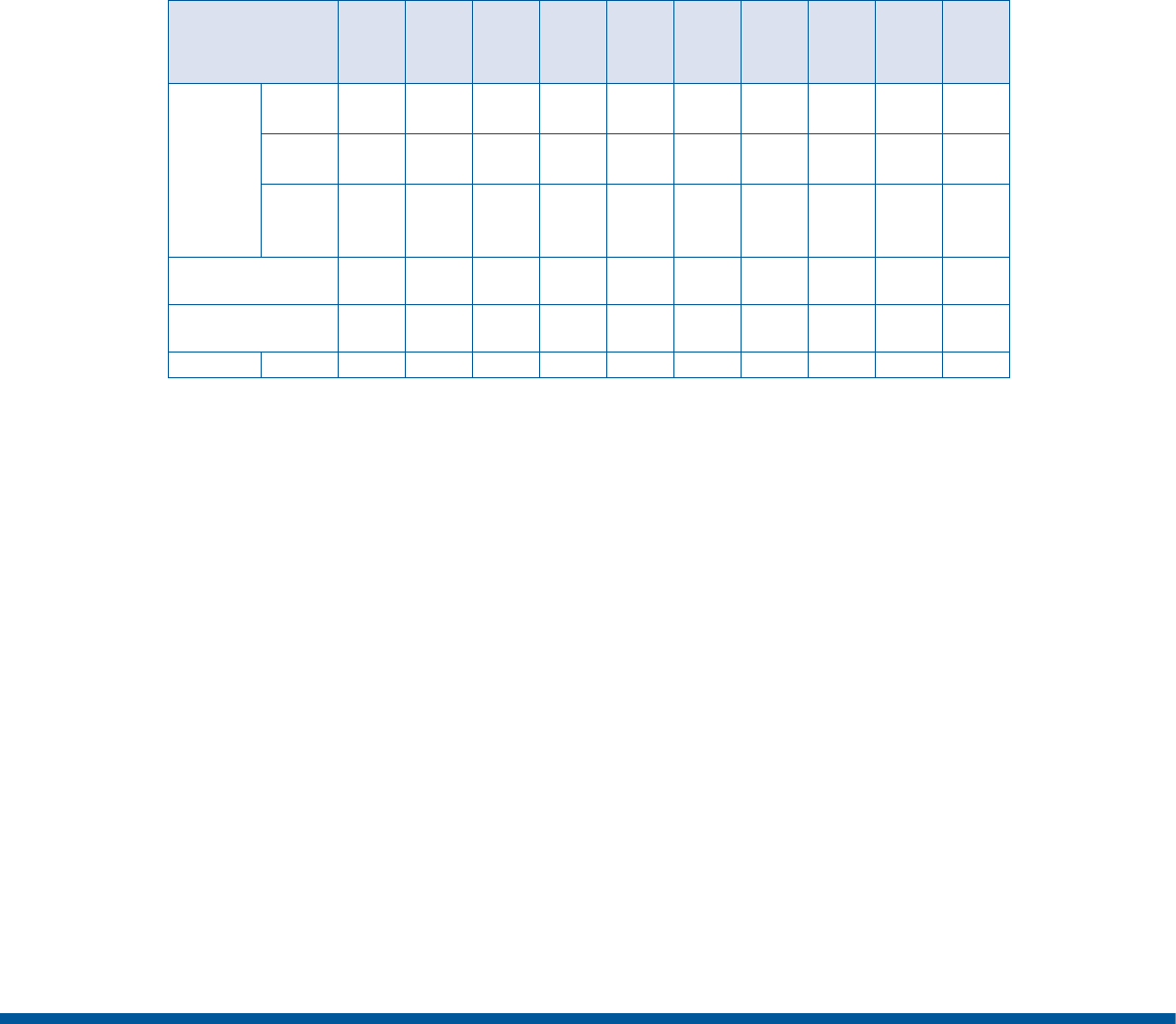

In some respects, landlords with larger portfolios can spread their risks. Two-thirds of all landlords

identified through the survey let more than one property (66 per cent) and 34 per cent only a single

property. Fifty-five per cent of individual landlords let more than one property, compared to 96 per

cent of companies. The mean number of properties held by individuals with more than one property

is 18 and 261 by companies, although the median number of properties held is lower at 5 and 82

properties respectively. Individual landlords are more likely to cluster their properties in one town

when compared to companies who are more likely to hold stock across different locations (Figure

3.6).

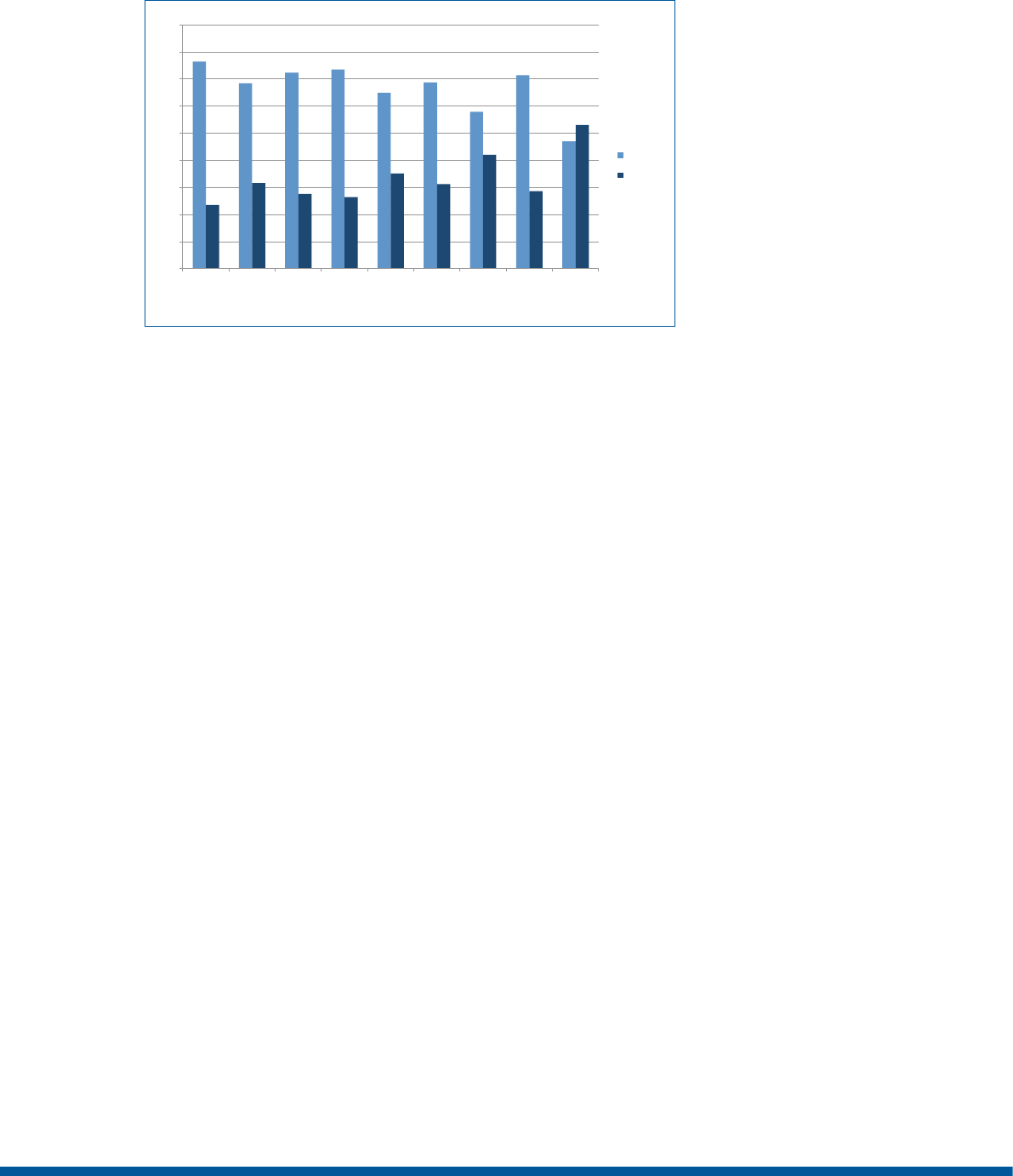

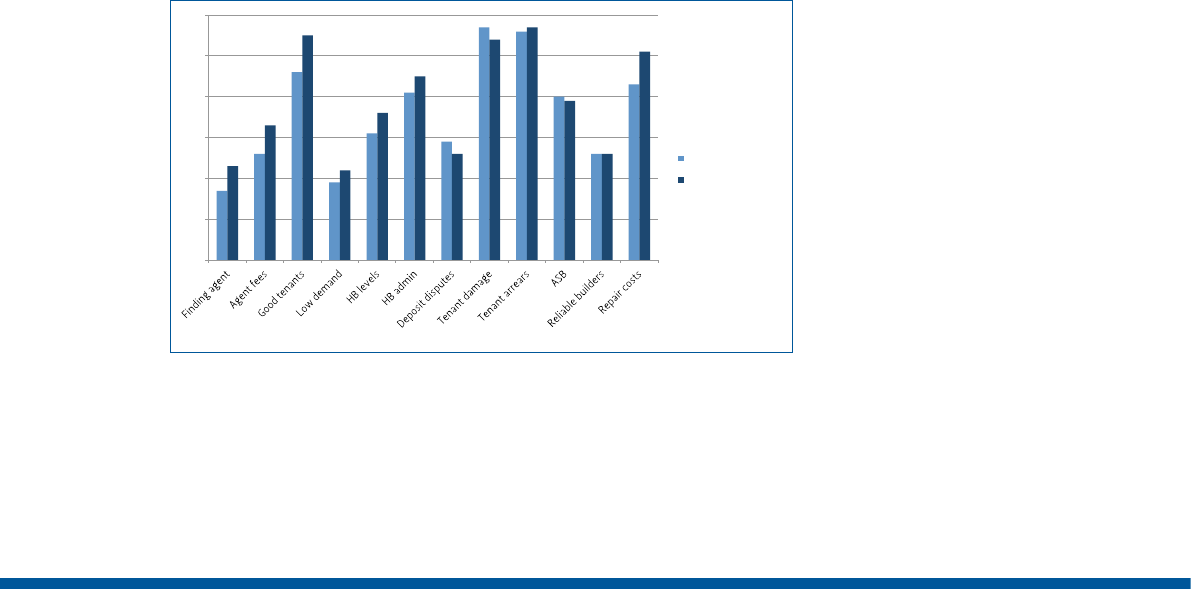

Figure 3.6: Location of properties (n=677)

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

All in one building All in one

neighbourhood

Mainly in one

neighbourhood

All in one town All in one county All in one region Scattered across

the country

(England only)

Individual

Company

Source: EHS-PLS 2010

Most landlords (74 per cent) bought the property, but 11 per cent inherited it and nine per cent had

it built. A total of 77 per cent of all landlords intended to rent property from the start. The majority

(68 per cent) of all landlords let houses rather than flats (31.5 per cent) and very few let rooms only

(one per cent).

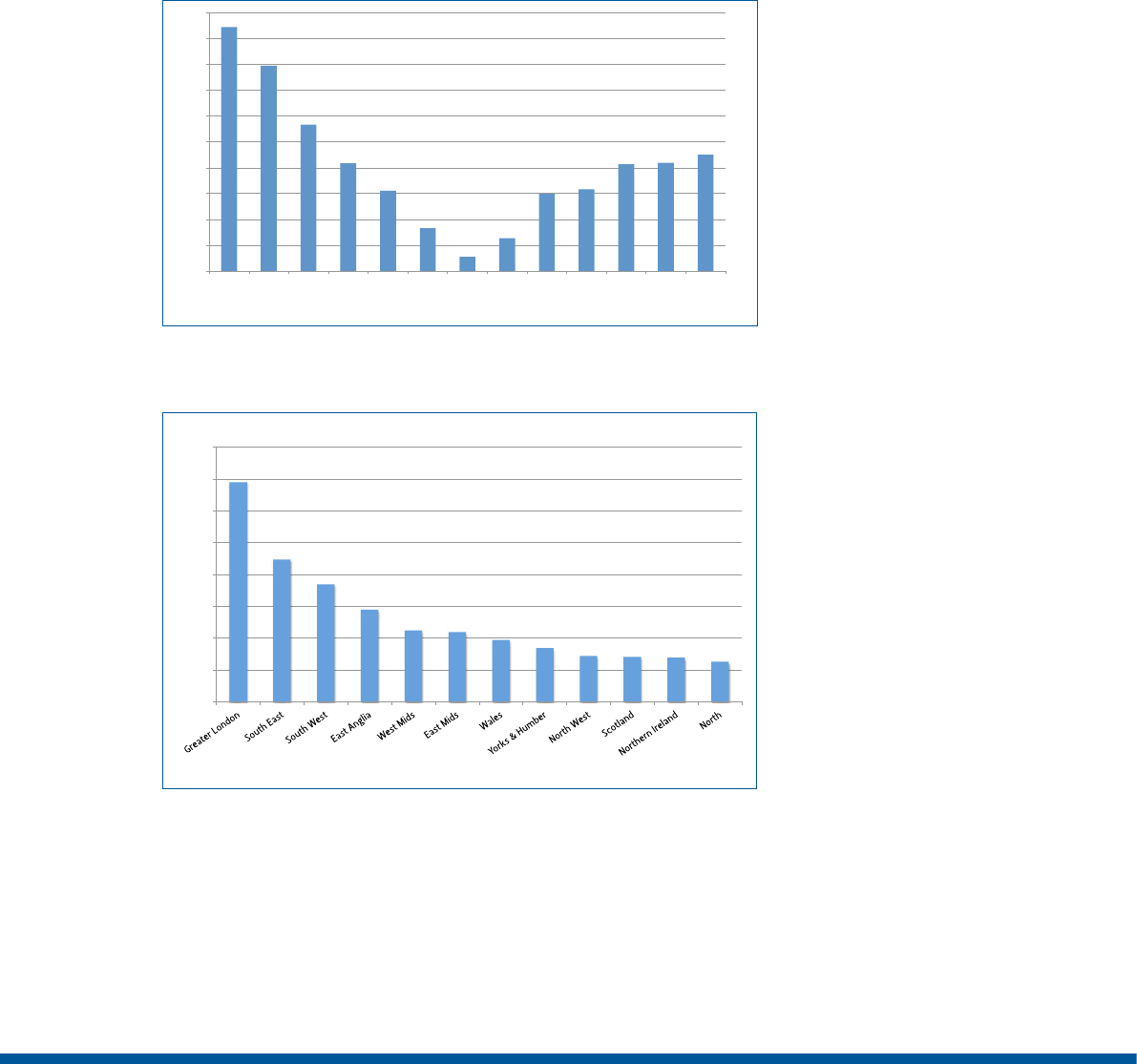

Greater proportions of landlords own more than one property in regions other than London and the

East of England (Figure 3.7). In London most landlords let a single property (53 per cent) compared

31

to the North East, where only 24 per cent of landlords let only one property. Landlords’ own home